In November 2022 the Goa Heritage Action Group released a special print edition of their magazine Parmal at a function held in Panjim. This issue is devoted entirely to Music and carries the title Aicat Mozo Tavo (Listen to My Voice).

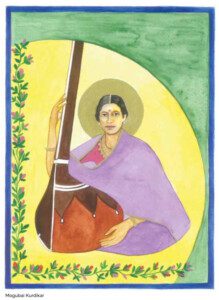

Mogubai

by Sonia Rodrigues Sabharwal

Included in the magazine is my essay on the contributions of Goans to India’s Art music written on the request of the editors Jose Lourenço and Vivek Menezes. A draft copy of the article is here.