The PDF of the essay is available here.

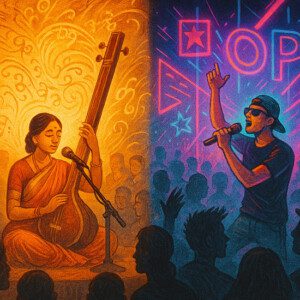

Western Pop Music Is Trash

A fact, not an opinion.

[Note: This is not a tirade against “the West.” I have lived in the West for nearly 4 decades, benefited from its enabling structures – educational, professional, and civic – admired its accomplishments, and count some of its thinkers among my intellectual mentors. For decades, even centuries, the West has presumed the right to critique, instruct, and grade the rest of the world. It is entirely appropriate now to turn the gaze the other way.]

The Illusion of Ubiquity

The global spread of Western popular music has little to do with merit. Its ubiquity is a byproduct of geopolitical muscle, not artistic worth. Since the mid-twentieth century, it has been pushed on the world through the West’s economic power, its media monopolies, and its cultural self-regard. Its reach is wide, but its depth is negligible.

Strip away the layers of hype and nostalgia, and what remains is a noisy, repetitive, and melodically barren heap. Western pop is, for the most part, manufactured sonic pulp. Its success says nothing about quality, and everything about distribution muscle and cultural imperium.

Defenders often retreat into relativism. All music is valid, they say. Every culture has its own values. That’s a lazy dodge. This is not an anthropological exercise. It is a value judgement.

Western pop is musically impoverished, lacking in complexity, subtlety, and emotional range. One can dress it up in academic theory or market statistics, but it remains what it is: crude, canned entertainment.

Noise Without Soul

The standard Western drum kit is built around noise, not tone. It provides punctuation but no melody. Contrast that with the Indian tabla, whose central loading allows for a rich range of tonal modulation, expressiveness, and even melodic interplay. Or with the drums of many African traditions, where rhythm is not mere background pulse but speech, structure, and soul. The difference here is not cultural. It is musical.

Layer the drum kit with 3 or 4 recycled chords, a predictable beat, and lyrics aimed at hormonal adolescents, and you have the full anatomy of Western pop. It is music built to agitate the body, not elevate the mind.

This is no small distinction. Indian music, in contrast, is built on an entirely different aesthetic foundation. Its aim is inward refinement, not outward stimulation. Rhythm is not absent – far from it. The rhythmic sophistication of Indian music makes Western beats look like a toddler’s playpen. Cycles of 5, 7, 10, 14, 16, and more, including fractional and additive patterns, are routine. The interplay of melody and rhythm is not just complex, but deliberate. It sharpens perception, steadies the breath, and engages the intelligence.

Western genres, by comparison, reveal their limits quickly. Techno turns the human ear into a receptacle for industrial waste. Bar music is wallpaper for the intoxicated. Hip-hop, once a vital voice of urban dissent, now loops endlessly around narcissism and violence. These are not the signs of a wholesome musical culture; they are symptoms of rot.

As for the heralded icons such as Dylan, Lennon, Presley – these are mediocrities inflated by cultural monopoly. Dylan, master of the monotone; Lennon’s thin melodic range; Presley’s affected swagger: this is the summit? Sinatra seems dignified only by standing among lesser men. Yes, there have been rare figures of genuine merit in the Western popular tradition. Ray Charles comes to mind, as does Louis Armstrong, whose phrasing, tonal invention, and musical authority reshaped what popular singing could be. But such figures are exceptions, not the rule. Meteors across an otherwise dim sky.

But the failure runs deeper than presentation. Western pop lacks melodic imagination and depth. Its tunes are often crude scaffolds for rhythm or attitude, not vessels of feeling. The relationship between words and melody is rarely organic. Verses are bent to fit the beat or else obscured in slurry delivery.

The phonetic quality of English itself doesn’t help: its consonants are jagged, its vowels often flat. There is little grace in how the language sits on melody. In some traditions – Italian opera, for instance – the fusion of word and tune is more refined. But in Western pop, that ideal barely exists. Much of the time, lyrics are simply slotted in, spat out, or buried beneath production noise. When they are audible, they are often trash talk: slogans, boasts, clichés, barked out with the finesse of a bludgeon.

In the Indian tradition, the situation is entirely different. Languages shaped by Sanskritic phonetics, fluid, vowel-rich, rhythmically sensitive, lend themselves naturally to melody. When set to music, the words don’t fight the tune, they flow within it. The language supports musical phrasing rather than resisting it. This alignment produces a natural grace, a fusion of sound and syllable that Western pop rarely approaches.

What Real Music Sounds Like

Indian popular music, especially in its golden era, shows what is possible when word and melody are inseparable. At the highest level of the art, it is impossible to say whether the words shaped the tune or the tune called forth the words. There is a seamlessness, a musical-lyrical intimacy that invites repeated listening and deep engagement. The poetry is not decoration. It is the song’s very soul.

The popular music of India, especially from the 1940s to the 1980s, stands as one of the great artistic achievements of modern civilisation. Its foundation had already been laid by K.L. Saigal, whose haunting voice and melodic sensitivity shaped the very grammar of what followed. The golden era that emerged built on that base, melding classical rigour with lyrical depth, and emotional intelligence with mass appeal. It also created an entirely new sound by absorbing and reshaping elements of Western orchestration – strings and harmony – not through mimicry, but through transformation. Yet the melodic line remained central, always sovereign. Orchestration played a supporting role, never the lead.

Kishore Kumar, Lata Mangeshkar, Mohammed Rafi, Asha Bhosle, were not merely singers; they were titans. Their artistry defies the puny categories Western pop reserves for “vocalists.” They immersed themselves in the emotional world of each song, bending melody and meaning at will, capable of turning a single phrase into theatre, prayer, seduction, or lament. These were sages of melody, not interchangeable mouths behind a mic. Their command over pitch, language, phrasing, and feeling makes most Western pop stars sound like wind-up toys.

Behind them stood a generation of composers whose range, originality, and technical command remains nonpareil: Anil Biswas, SD Burman, Naushad, Roshan, Madan Mohan, Salil Chowdhury, OP Nayyar, RD Burman. And from the South, Ilaiyaraaja, whose genius spanned everything from Carnatic depth to Western harmony, often within a single composition.

The reach of these musical wizards was not confined to India. Their music followed the diaspora across continents, from Trinidad to Fiji, Mauritius to Guyana, Surinam to South Africa. In the Gulf, in the UK, in Canada, even in Russia, their voices became the soundtrack of weddings, longing, exile, joy. For more than 60 years, Lata and Asha gave voice to the inner lives of millions, across languages, continents, and generations. Their songs accompanied births and deaths, longing and celebration, exile and return. No Western singer, living or dead, has ever held such sway over so many hearts, for so long, and with such constancy. This is not poetic license. It is arithmetic.

And still, the West sees none of it. When it thinks of Indian popular music – if it thinks of it at all – what comes to mind is present-day Bollywood kitsch: garish visuals, digital screeching, choreographed noise. The true tradition remains unseen.

This isn’t nostalgia. It is a reckoning, one grounded in artistic seriousness and enduring aesthetic values.

Of course, nostalgia has its place. Music binds us to memory: a childhood home, a parent’s voice, the rhythm of a time when the world was still being discovered. I understand why people cling to the songs of their youth. They are sown into lives and places, the grain of vanished seasons. But memory is not a measure of merit. Maturity demands discernment, and taste must evolve. To grow up is, in part, to grow out of what once dazzled and reach for what endures. The ability to move beyond Western pop is a test of musical intelligence.

None of this is a blanket rejection of Western music. The Western classical tradition stands apart and must be acknowledged with seriousness and without hesitation. Bach’s polyphonic architecture, Beethoven’s visionary daring, Schubert’s melancholy lyricism, Tchaikovsky’s dramatic sweep – these are works of immense depth and dignity. At its best, Western classical music carries undeniable emotional power and intellectual depth. It may not match the melodic profundity or rhythmic complexity of Indian classical traditions, but it remains a towering achievement in its own right.

But the focus here is pop, and the verdict is plain. Western popular music isn’t misunderstood. It is grotesquely overrated. Hollow at the core, wrapped in noise, kept aloft by marketing. Not an emperor without clothes, but a street performer in rented rags, amplified by the machinery of empire. Overvalued and a museum of bad taste, endlessly curated.

The Silence Will Not Last

Sooner or later, the dynamics will change. As the economic and political centre of gravity shifts toward Asia, cultural perception will shift with it. The West will retain its visibility, and that’s as it should be. But Indian voices will no longer be invisible or unheard. The world will simply have to listen.

Lata’s aching purity. Kishore’s fire and playful invention. Rafi’s gentility. Ilaiyaraaja’s vast invention. These are not regional curiosities. They are world-class forces.

History will make room. It always does – for what endures.

Epilogue

Some have mistaken my critique as a category error.

Melody, rhythmic complexity, emotional range, and the organic fit between language and musical line are not parochial or culture-bound concerns. They are constitutive elements of music as an expressive human art form. One need not belong to a particular tradition to perceive whether a melody moves, a rhythm intrigues, or a text flows naturally within its musical setting. Cultures may weight these elements differently, but their relevance is shared. I uphold melodic richness, rhythmic intelligence, and organic phrasing as musical first principles – and by those measures, Western pop is bankrupt.

My critique of Western pop is not that it is different, but that within these shared evaluative dimensions, it falls short. Furthermore, Western pop has globalised itself aggressively. It has marketed itself as the standard – a universal cultural product – and must therefore accept being evaluated against standards broader than its own internal formulas. My aim is not to appear “balanced,” and I make no concessions to false equivalence.

April 2025