by Rajan P. Parrikar

First published on SAWF on January 22, 2001

Rajan Parrikar (Cape Canaveral, Florida, 1989)

Photo by: Dr. Anand Bariya

Namashkar.

In the realm of melodic music the tradition of India is without equal. Nothing else comes close. The Europeans and Americans, the self-appointed adjudicators of every activity under the blazing sun, who once thought their finest melodies to be works of high Art, have now discovered to their utter dismay that they have done no better than wrestle with kindergarten level ditties when they have not been otherwise churning out noise. The vast terrain of Indian ragadari music has nourished and nurtured a teeming web of melodic life of every conceivable level of complexity and aesthetic measure. The very high end of this spectrum is a nest for an aristocracy of ragas that represents the acme in human melodic thought. To this exclusive commonwealth belongs our raga-du-jour, Shree, at once recognizable for its forbiddingly haunting and deeply meditative mien. For the musician, it is among the most difficult ragas to master. For the rasika, it is a fulfilling emotional purchase.

Throughout the following discussion m = teevra madhyam.

Shree is an ancient raga of the Poorvi that corresponding to the 51st melakarta of the Carnatic paddhati, Kamavardhini, with the following swara set: S r G m P d N. Shree is also a raganga-raga lending seed material to several other sub-melodies (eg., Triveni, Jaitashree, Shree Tanki and so on). Raga Shree of the Carnatic paddhati is an altogether different bloke although there exists a curious relationship: a simple flip-flop of the swaras of the Carnatic Shree from or to their vikrita forms yields an approximate contour of the Hindustani Shree. Notice that a similar correlation holds true for other name-congruent pairs, eg., the Carnatic Hindolam and Hindustani Hindol or the Carnatic Bhoopal and Hindustani Bhoopali.

The nominal arohana-avarohana set of Raga Shree may be stated as:

S r, (G)r (G)r m P, N S”::S”, r” N d P, d m G r, (G)r S

The aroha-avaroha does not convey much and must be seen as a preliminary aid; it is really an ex post facto construction. Knowing a raga involves investigation of its ‘biochemistry’, the position and pramana of all the swaras employed, their interrelationships and the prayogas. Shree is meend pradhana, of vakra build, and requiring of special swara uccharaaa (enunciation). It places unusual demands on the musician’s reflective daemon and calls for cultivation of proper habits of mind and voice. In the hands of a master Shree can lead to an ennobling experience. Lesser hands given to playing ducks and drakes ought to be persecuted to the highest extent allowed by the law of the land.

In the arohi movement Shree omits the gandhar and dhaivat. The central idea is the coupling of the komal rishab and pancham, the vadi and samvadi swaras, respectively. The intonation of the rishab tugged with the gandhar and the meend-laden rishab to pancham coupling define Shree’s signature. Therein also lies the key to its gambheer, maestoso personality. The r-P-r coupling cuts both ways. S, r and P and are extremely strong swaras (nyasa bahutva); the m, d and N swaras assume subsidiary values. The avarohi retreat is tricky as the entire locus cleaves through a minefield of meends. The definitive movement – r” N d P, d m G r, S – is an important signpost of raganga Shree. Execution of fast tans in Shree is tough. It can be easily verified that a rapid run of rmPN is non-trivial (since it tends to slide into rmdN). Recognition of such speedbreakers dictates the construction of tans; the prescription leans towards avarohi tans.

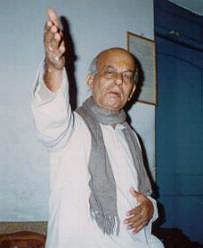

Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang”

The essence of Shree is difficult to convey through the written word alone. Fortunately, today’s technology permits a multimedia exposition. To get the raga’s gestalt it is recommended that you allow some of its key tonal movements to ricochet in the walls of your mind for at least a week or so.

We have cobbled together two representative chalans, one each for the poorvanga and uttaranga regions. The voice is Nachiketa Sharma. Observe the treatment accorded the rishab, the r-P-r interaction and the meends in descent.

First, the poorvanga:

S, (S)r, (G)r m P, P (P)r, (G)r (r)P,

(P)m P d m G r, (G)r (r)P (P)r, G r S

The uttaranga chalan:

m P N, N S”, mPNS”r”, (G”)r” (G”)r” S”,

r” N d P, (P)m P d m G r, (r)P (P)r, G r S

Some of the finest recorded instances of Shree are loaded in the audio segment that follows.

‘Light’ renditions in this raga are uncommon, its complex structure perhaps serving to thwart attempts to tame it. In the movie ANDOLAN (1951), the flute maestro Pannalal Ghosh composed a song and had his wife Parul render it: Prabhu charanon mein.

We open the classical innings with three splendid compositions of Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang.” The raga lakshanas emerge with crystal clarity in Jha-sahab’s own voice packed as it is with anubhava (there is no good English equivalent of this beautiful word; “experience” doesn’t quite cut it). First, the vilambit in dheema Teentala:

gyana na pave guru bina gyani

gurupada raja anjana ankhiyana mein

mana driga dosha mitave

Shiva Sanakadi rate Bhrahmadika

nisi vasara charanana chitta lave

“Ramrang” Hari guru mein bheda na veda na’ita nita gave

Ramrang’s druta bandish retains the textual bhava. Notice the fit of the words with the melody and tala. The composition includes, what is known as, a vi-sam, where the accent is moved off the the sam and onto the second beat of the tala cycle:

guru ke paga pariye dhariye dhyana mana

nisi vasara sumiriye nama

pave gyana mana guniyana mein

agama apara nada veda

guru bina pave kabahuna bheda

“Ramrang” bhava bhagati kari dhyave aave jo sharana mein

Ramrang’s brisk tarana mapped tp the 14-beats Ada Chautala:

Jha-sahab also tosses in a rendering of the well-known traditional bandish, eri hoon to, punctuating the development with shoptalk.

Chand Khan

Among the earliest khayal schools, Delhi Gharana now lies dormant. This rich and lyrical style was once the home of the likes of Achapal, Tanras Khan, Bundu Khan and Mamman Khan. The last distinguished representative of Delhi was Mamman’s son, Chand Khan. It is a pleasure to offer a glimpse of Chand Khan’s artistry in this prized recording. Notice his mudra “Chand Piya” in the druta cheez.

Another vintage rendition of Laxmanprasad Jaipurwale of the “Kunwar Shyam” tradition (see the archive for an exclusive feature on him). He sings the bada khayal traditionally dear to the Gwalior musicians – gajarwa baje – in vilambit Ektala.

The most popular Shree melody of our times is the sublime composition of Pandit Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande (“Hararang”) – Hari ke charana kamala – famously rendered by D.V. Paluskar in what turned out to be his swan song. The story of this recording is retailed in the Appendix below.

Hari ke charana kamala nisadina sumira re

bhava dhara sudha bheetara bhava jaladhi tara re

jo’i jo’i dharata dhyana pavata samadhana

“Hararang” kahe gyana, abahu chita dhara re

Bhatkhande’s chef d’oeuvre meets its match in the ecumenical genius of Amir Khan.

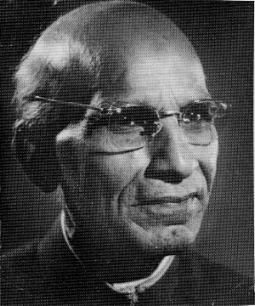

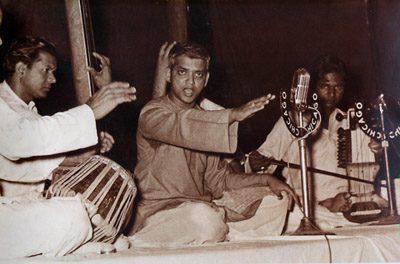

D.V. Paluskar, with Ram Narayan on sarangi

The Gwalior staple, gajarwa baje, cast originally in Tilwada tala, is offered by Ulhas Kashalkar. He later launches into the druta composition eri hoon to. Compare it with Jha’s sahab’s excellent delivery of the same item.

The doyen and teacher to many of Maharashtra’s musicians, the late violinist and vocalist Gajananrao Joshi.

Like other grand ragas, Shree is primarily the province of the vocalist. Nevertheless, the occasional instrumental performance transcends the run-of-the-mill. One such is by the cheej pijja-loving (naked) Emperor of San Rafael, Mr. Alubhai Khan.

A latter day Salamat Ali effortlessly summons an austere Shree ambience…

…but an earlier orgiastic excess with his brother Nazakat Ali must be credited to youthful indiscretion.

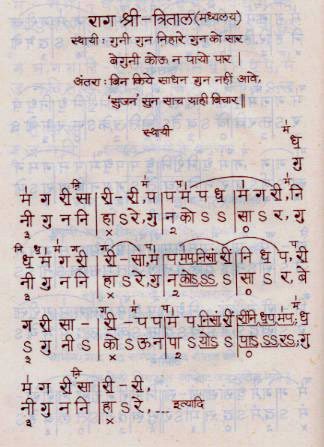

K.G. Ginde’s notation of Ratanjankar’s bandish

The Atrauli-Jaipur conception of Shree is quite grand as witness the recordings of Mallikarjun Mansur. Here he assays the A-J chestnut kahan mai guru dhoondana ja’oon:

Shruti Sadolikar‘s version reveals a variation on the bandish.

After Ramrang and Bhatkhande we come to the last of the great vaggeyakaras featured in this selection: S.N. Ratanjankar. His guni guna nihare is conveyed by his pupil K.G. Ginde. Shri Ginde’s work in documenting Ratanjankar’s 600+ compositions in magnificent calligraphy, with astounding attention to notational detail, defies description and is a work of Art in its own right (see sample on this page).

guni guna nihare guna ko sara

beguni ko’u na payo para

bina kiye sadhana guna nahin aave

“Sujan” suna sacha yahi bichara

We come to the last item of the Shree hit parade. C.R. Vyas has composed a tribute to his guru Jagannathbuwa Purohit “Gunidas”: kahe dara pa’oon mai barse krupe mope jaba more Jagatanatha.

Appendix

D.V. Paluskar’s last recording

Excerpts from Down Melody Lane by G.N. Joshi

“…Most classical musicians complained that it was very difficult for them to give a perfectly satisfactory performance in just 3(1/4) minutes. I therefore felt that if allowed to perform unrestrained for 15 to 20 minutes, they could be taped and later an edited version of the performance could be used on a disc…When approached [D.V. Paluskar] enthusiastically agreed to cooperate. During the Ganapati festival of 1955 he had a number of singing assignments, the last one being at Vile Parle. He promised to come immediately after the last engagement and accordingly he came but he was very tired after the exertions of the successful programme. He wanted to postpone the experiment to a later date, but I told him that it did not matter very much if his voice was not in good shape because the recording was intended to be for experimental purposes alone and not for issue. It was about 2.30 p.m. when we went to the studio and made arrangements for the session. He was to leave for Pune at 5.00 p.m. by the Deccan Queen. I persuaded him to record a 20 minute long exposition of a raga which could cover the full length of our tape. Thereupon he sang and recorded Raga Shri. After the recording I rushed him off to the station in my car and waved him off. That was the last I saw of him. Hardly 3 weeks later he was suddenly taken ill with a mysterious illness and died on 26th October 1955. It was the Dassera day and the news gave the entire music world a stunning shock. The recording made by me three weeks earlier proved to be his last. From this 20 minute experimental tape of Raga Shri, I had to reconstruct a homogenous performance of the raga to fit on a 78 rpm record. I achieved this intricate task after listening to the tape repeatedly for over 18 hours…When I played this 6(1/2) recording to the late Pandit S.N. Ratanjankar (who was then considered to be the greatest authority on Indian classical music) he never even suspected that it was in fact an abridged edition of a 20 minute performance. He congratulated me and our recording engineer and expressed his desire that we should record his performance in the same way. Accordingly we recorded Raga Yamani Bilawal sung by him, with V.G. Jog accompanying on the violin. Both edited versions – Bapurao Paluskar’s and Ratanjankar’s – when put in the market kept selling for years without a single person discovering that they were edited… After the advent of the LP records this method was not necessary as an artist now had a much longer recording time than on the original 78 rpm records. Usually after a record was issued the original was sent to our factory in Dumdum. I had kept a copy of the tape of the Raga Shri since this experiment had been my own. Bapurao died before LP records were introduced. I therefore thought of issuing the 20 minute performance of Raga Shri on an LP…Since the recording was only meant as an experiment, I had ignored the fact that Bapurao’s voice sounded husky and tired. The performance was quite up to the standard in other respects. A tough controversy ensued between me and the technical department over this. I pleaded for the release of this record, pointing out the circumstances under which the recording was done…After a two-year battle of words my viewpoint was accepted and the LP disc is, even today, on our prestige repertoire. When I bade goodbye to Bapurao at V.T. station, he had promised to come back for recording within a month, but alas, that was not to be. Cruel destiny snatched him away suddenly and prematurely, when he was only 34 and at the height of his career.”