by Rajan P. Parrikar

First published on SAWF on June 25, 2001

Rajan P. Parrikar (Boulder, Colorado, 1991)

Namashkar.

Shankara, an epithet of Lord Shiva, invokes the boundless energy and grandeur of His eternal bond with music and dance. The image of Shiva as Nataraja, the cosmic dancer, has kindled the imagination of generations, inspiring an unbroken tradition of artistic expression. His divine essence captures the ultimate Indian aesthetic ideal, encapsulated in the immortal words: Satyam Shivam Sundaram – Truth, Divinity, and Beauty.

Raga Shankara, a melody of extraordinary depth and distinction, transcends mere nomenclature to embody Shiva’s very nature. It mirrors His celestial attributes: raudra (fierce), veera (heroic), mercurial, and, in moments of serene stillness, profoundly cool. This majestic raga, a veritable force of nature, beckons us to explore its exhilarating melodic terrain.

Throughout the ride, M = shuddha madhyam and m = teevra madhyam.

Raga Shankara

This shadava jati raga employs all shuddha swaras except madhyam and is filed under the Bilawal that corresponding to the 29th Carnatic melakarta, Shankarabharanam. Two definitive threads constitute Shankara’s woof and they are:

(1) S (P)G P, P (R)G–>S (poorvanga marker)

(2) G P N D S” N (uttaranga marker)

A swara in parenthesis represents a kan (grace) imparted to the one following it.

Let us amplify on the dominant themes. In (1) above, the gandhar receives a tug of pancham in arohi prayogas – S (P)G P – and a kan of rishab in avarohi prayogas – G P (R)G . The “–>” placed between G and S denotes a meend-laden retreat grazing rishab en route (a la Bihag). The rishab‘s role is paradoxical – it is durbal (weak) yet vital for the manner in which it services G and P.

In the uttaranga signpost (2), nyasa on N following G P N D S” N is required. An abhasa of Bihag prevails but the absence of M keeps it in check. The Bihag-like movement N–>P, grazing D along its declining locus, is the uttaranga foil for the G–>S gesture indicated earlier; a little reflection shows how the Bihag presence permeates Shankara’s strata.

Obiter dicta: P and N are crucial nyasa sthanas. The rishab is occasionally brightened for effect in the tar saptak as in, say, PP N S” R, S”. This may induce a tirobhava by inviting Hamsadhwani where rishab is dominant. The dhaivat is subdued, descried in quick clusters such as SGPDPP or GPDGP.

The aprachalita Raga Malashree (to be treated later in this feature) has a mild alliance with Shankara but there the dhaivat is varjit. Comparisons are often drawn between Shankara and Hamsadhwani but the points of departure are significant and should be evident by now. Linear up and down runs, the norm in Hamsadhwani, do not sit well with Shankara. Instead, the tans are conceived in zigzagging clusters such as SGPDPPNDPP, GPNDS”NPP and so on.

The foregoing raga behaviour is now amplified through actual demonstration. An aroha-avarohana set is first proposed (D and R are not explicitly depicted in the grazing instances described earlier). Bear in mind that the aroha-avarohana is a basic mnemonic device and is of limited value in understanding the finer points of raga structure.

S, (P)G P, N D S” N, S” :: S” N–>P, G P (R)G–>S

A sample chalan ropes in the highlights (the square bracket around S” signifies the gamaka centred around it):

S (P)G P, G P N D [S”] N, G P N S”

P N S” G”–>[S”] N, P N D S” N–>P, G P DG P (R)G–>S

The vocalist in the above clips is Nachiketa Sharma.

Assembled on the Shankara tableau are many of the finest recordings extant. Its praxis is fairly uniform throughout the Hindustani landscape, its dhatu regnant across almost all stylistic and regional schools. The variations, where they prevail, are primarily in the pramana (proportion), in particular the treatment of rishab. The textual content of most of the compositions speaks to the Lord Shiva’s visage and mien. I intend to keep the commentary terse from this point on as we make our way through the catalogue.

K.L. Saigal

We begin with K.L. Saigal‘s gem, composed by Khemchand Prakash for the movie TANSEN (1943). The mise-en-scène has Saigal-sahab pacifying an agitated pachyderm: rum jhum rum jhum chala tihari kahe bhayi matwari.

Saigal’s tsunamic splashdown on the Indian musical shores in the early 1930s brought with it radically new waves of musical expression. The germ of Pandit Kishore Kumar‘s gayaki can be laid directly at Saigal’s door. Under Rajesh Roshan‘s direction in DES PARDES (1978) Panditji offers an unusual twist on Shankara.

From SUSHEELA (1963), Mubarak Begum, for composer C. Arjun: bemuravvata bewafa.

The brilliant Dinanath Mangeshkar of Goa died young (in 1942) but his samskaras live on in his daughters Asha and Lata. Among his most famous renditions: Shankara bhandara bole.

Shankara’s virile bearing comes to flower in the intonational certitude inherent to dhrupad-dhamar gayaki.

N. Zahiruddin and N. Faiyazuddin Dagar‘s dhamar: chaunka pari ho.

Dinanath Mangeshkar

This dhrupad set to Sooltala of 10 matras is from a live Gundecha brothers performance: varun ri mriga drgana ko.

Siyaram Tiwari‘s full-bodied, forceful style originates in a different stream of the dhrupad tradition with its roots in Darbhanga, Bihar: Hara Hara Mahadeva.

Basavraj Rajguru

The canonical vilambit khayal of “Manrang” invokes Lord Shankara while paying tribute to the khayal pioneer, Nyamat Khan “Sadarang.”

Basavraj Rajguru‘s old All India Radio recording: Ada Mahadeva been bajaa’i, Nyamat Khan piya Sadarang kara karama dikhaa’i.

Bhimsen Joshi has recorded some forgettable Shankaras in the 1980s. This cut of a traditional chestnut, so janu re, barely passes muster. Keep your ears peeled for the brush with teevra madhyam (a la Shuddha Kalyan), first heard ~ 0:34 into the clip.

Roshanara Begum redraws the popular druta composition, mAthe tilaka dhare, fitting it to vilambit Ektala.

An impassioned cri de coeur by Anjanibai Lolienkar of Agra gharana: balama balama balama.

Abdul Karim Khan

Mr. Jasraj (of Viagra gharana) responds by lending a free hand to his spiritual libido. The musician in Banditji occasionally threatens to break out: vibhushitananga riputtamanga.

Abdul Karim Khan‘s felicity with swara is stamped all over this recording. The caress of the dhaivat at ~ 0:06 is delicious. Watch out for a Hamsadhwani-like PNS”R G (~ 0:35) : eri aaja suhaga.

Also check out his 1905 vintage tarana.

Several renditions of the popular kala na pare are in circulation. My pick is this stylish assay by Sawai Gandharva.

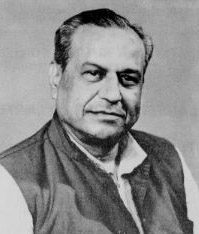

Kumar Gandharva makes the dust fly in an erumpent display. The composition is his very own:

sira pe dhari Ganga, kamara mruga chhala

mundaki galamala, hatheli soola saje

Pinaki mahagyani, ajaba roopa dhare

dulata dula aave, dimaru dima baje

Kumar Gandharva

A habit of listening regularly to Kesarbai Kerkar has the effect of rendering one intolerant of mediocrity. Everything about her music is stupendous and those tans, the living end. This composition is in madhya laya Jhaptala, aaye ri.

My choice for the finest Shankara in this collection, perhaps the greatest Shankara recording there is: an unpublished mehfil of Kishori Amonkar. It is only given to those possessed few to do music at this level. The traditional bandish, anahata ada nada bheda na payo.

Basavaraj Rajguru re-vists with an Agra hottie conceived by one of that school’s influential composers, Tasadduq Hussain Khan “Vinod Piya” of Baroda. Take measure of the syncopation: aiso dheeta langara kare jhakajhori.

The same cheez, performed on the sitar by Vilayat Khan.

Shubha Mudgal takes taleem from Ramashreya Jha

Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang” has composed delightful melodies in Shankara, most of them yet unpublished. His Shiva-stuti is informally sketched by Shubha Mudgal specially for this feature: chandrama bhala biraje.

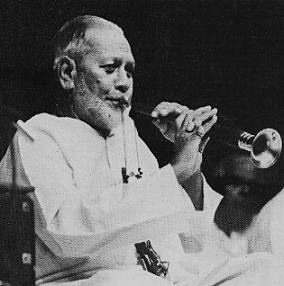

Swara-smithing is Bismillah Khan‘s forte and this old All India Radio recording, pure ear candy.

Bismillah Khan

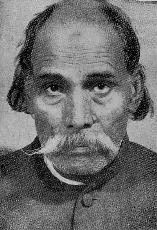

In his day, Rajab Ali Khan (1874-1959) was known as much for his musical acumen as for his picaresque ways. A master vocalist, he was also proficient on the rudra veena, sitar and jala-tarang. Several musicians of high standing learnt from him, among them his precocious nephew Amanat Khan, Nivruttibuwa Sarnaik, Ganpatrao Dewaskar and others. Lata Mangeshkar is said to have taken taleem from Rajab Ali during her apprenticeship under Amanat Khan in Mumbai. Note that Amanat Khan (Rajab Ali’s nephew) and Aman Ali Khan Bhendibazarwale are two different musicians. Amir Khan was influenced by both of them. [I would like to thank Jyoti Swarup Pande and Debashish Chakravarti for their input in clarifying this.] Prof. B.R. Deodhar‘s published analects contain several charming stories of Rajab Ali (see Appendix at the end of this essay). Some of his archived recordings have been made available in recent years, among them a Shankara. We have heard this bandish earlier: mathe tilaka dhare.

That cheez also shows up with an emended mukhda as witness the Gwalior treatment by Narayanrao Vyas.

Kishori Amonkar

It is also Mohammad Hussain Sarahang‘s choice for a soirée in Kabul.

Our Shankara expo concludes with an old Gwalior favourite, sanwal do mhane bhayo, by Malini Rajurkar.

Three basic prakars of Shankara – Shankara Bharan, Shankara Karan and Shankara Aran – have been traditionally acknowledged and all of them have gone out of fashion. Furthermore, no consensus prevails on their swaroopa. A hybrid involving Kedar and Shankara known as Adambari Kedar, has been discussed in an earlier feature (see On the Variants of Kedar). In the remainder of this article we briefly address a few allied Shankara melodies.

Raga Shankara Bharan

The few old surviving dhrupads are at sixes and sevens over the nature of this raga. Typically, the basic Shankara frame is extended with one or both madhyams. In the version advanced by Ali Akbar Khan, a soupçon of Bihag and Kalyan is injected via the two madhyams. The teevra madhyam is subtle, a la Shuddha Kalyan: P->m->G. The tonal phrase G M N–>D–>P stands out.

Raga Shankara Karan

Mr. Alubhai virtually eliminates the rishab and ropes in elements of Khamaj via the komal nishad. The play on two nishads is masterly, so are the prayogas involving the madhyams.

K.G. Ginde purveys a very different Shankara Karan. Here, too, the rishab is severely diminished. The teevra madhyam is deployed to evoke chhayas of both Kalyan and Hindol. The compositions are due to Ginde’s guru, the great vaggeyakara, S.N. Ratanjankar.

K.G. Ginde

Raga Shankara-Bihag

Rais Khan exploits the collegial kinship of Shankara and Bihag in this winsome hybrid.

An enchanting recital in this jod-raga by the grand old man of Gwalior Krishnarao Shankar Pandit: nijapada davi atritanaya.

Raga Malashree

This old raga stands out for its use of just four swaras: S, G, P, N. The nishad is alpa which further reduces the tonal space for elaboration. In performance, however, teevra madhyam is sometimes employed as in P-m-G.

Pandit Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang” gives a tonal briefing peppered with pertinent remarks.

We ring down the curtain with Alubhai.

Acknowledgements

My heartfelt thanks to Romesh Aeri, Ashok Ambardar, Ajay Nerurkar, Guri Singh and Anita Thakur.

Appendix

Rajab Ali Khan‘s capers have been recorded in Prof. B.R. Deodhar‘s book Pillars of Hindustani Music (Popular Prakashan). Some excerpts:

…Have you heard of a Court case in which a shagird (formal disciple)sues the ustad for refund of fees paid by him or her at the time of the black-thread ceremony? This is what happened in the case of Khansaheb Rajaballi Khan. The interesting feature of this case was that the Counsel for the defendant was none other than the late Pandit Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande…Khansaheb, not being well-versed in legal matters, sought Pandit Bhatkhande’s advice. Panditji agreed to fight the case on Khansaheb’s behalf. When the matter came up in Court, Panditji argued that the payment made at the ganda-bandhan (black-thread) ceremony being guru-dakshina, i.e. in the nature of a gift to the guru, the disciple can in no circumstances ask for its repayment. The Court, accepting this reasoning, decided in Khansaheb’s favour…

Rajab Ali Khan

…Khansaheb’s concert tours used to cover several cities and he would earn a sizeable sum of rupees seven to eight thousand, before returning to Dewas. Because of his prodigal ways it was not long before this fortune was spent on his own extravagances and hospitality to intimate friends. Then the borrowings from money-lenders, grocers, other shopkeepers and confectioners would start. The shopkeepers, knowing their customer only too well, would decline to supply goods on credit when the borrowings had crossed reasonable limits…On one occasion, the money-lenders, grocers, clothiers all stopped credit but the confectioner continued to provide stuff on credit. One day a relation of Khansaheb, who lived in a distant village, came on horseback to visit Khansaheb. Khansaheb extended a cordial welcome to him and ostentatiously told him to go to a confectioner and get five or ten seers of jalebi. The guest protested that his horse ate grass and not jalebi. Khansaheb replied, “You happen to be the guest of a great artiste. Your horse, while he is under my roof, must eat jalebi.” The horse was indeed fed on jalebis. Khansaheb did not have any cash even to buy fodder for the horse but since the confectioner had still not cut off credit, jalebi was still obtainable…

…Having come to know that a visit to Vazir Khan was a must before seeking audience with the ruler [of Rampur], Rajaballi Khan went to the former’s mansion…The two went inside. Rajaballi Khan’s companion bowed low and then squatted on the ground like a lowly dependant. Vazir Khan was seated in a silver-encrusted chair. Rajaballi Khan made a bee-line for his seat and sat on an adjoining chair. He even went so far as to take a few puffs on Vazir Khan’s hookah. Vazir Khan, although really very angry at this impertinence, was outwardly calm. He politely enquired after Rajaballi Khan who replied that he was a singer, been player and a disciple of Khansaheb Bande Ali. Vazir Khan said, “Yes I know,” and made some uncharitable remark about the kind of instrument Bande Ali was using. Rajaballi Khan replied “But it had a far sweeter sound than your Rampuri drum-like been.” Since Rajaballi’s first interview was so explosive the prospect of his being able to secure an audience with the Nawab was not very bright. But Rajaballi, ill-mannered as he was, had brought a letter from the Kolhapur ruler. Since not to grant him an interview would be discourtesy to the Maharaja, the Nawab decided to see him.

The Nawab sent for him the same night…Rajaballi used to say that the Nawab was a very skilled singer and his layakari (sense of rhythm) was very good. He knew innumerable dhrupads and dhamars by heart. However, he did not pay as much attention to swara (tonal purity) as he should have. After his rendering of a song, the Nawab turned to the assembled musicians and said, “Tell me, have you heard any singer who can equal me in layakari and tonal purity?” All the musicians instantly chorused, “No Your Highness! We have neither seen nor heard anyone of your calibre!” Nawabsaheb turned to Rajaballi and asked, “Rajaballi, what is your opinion?” Rajaballi replied, “My opinion is identical with what the others have said.” But this somehow did not carry conviction with the Nawab. He repeatedly pressed Rajaballi for his true opinion and finally asked him to swear by Allah and the Koran and give his true opinion. Thereupon Rajaballi said “Your Highness! I have visited many princely houses and palaces without coming across any Raja who knows as much music as you do or who can sing like you.” Nawabsaheb countered this by saying, “I am not asking you to say where I stand with respect to the other princes. How do I rank among professional musicians? I want you to tell me that.” To this Rajaballi replied, “Even the children of musicians are better than you.” Nawabsaheb’s face grew crimson with rage when he heard this. “I would have had you shot this instant,” the Nawab barked, “but unfortunately you have come here with a letter from the Maharaja (of Kolhapur). I am helpless. But get out of my state immediately.” Rajaballi was paid Rs. 500/- and expelled from Rampur without delay…