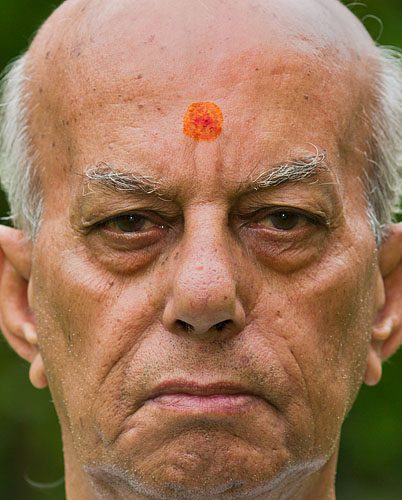

by Rajan P. Parrikar

First published on SAWF on October 30, 2000

Rajan P. Parrikar (Colorado, 1990)

The Sarangs are ragas of the early afternoon and have their provenance in folk music. Their effective expression in the classical idiom requires familiarity with their rustic antecedents. This widely loved enclave of Sarang melodies is the subject of our current discourse.

First, some preliminaries:

– Gaud Sarang is not included in this selection since it is a misnomer. There is no Sarang anga in Gaud Sarang. If the publication Raga Guide (Nimbus) asserts otherwise then its authors “may be excused only on the grounds that before deluding others they have taken pains to delude themselves” (to paraphrase Sir Peter Medawar). See Raga Gaud Sarang – An Exegesis for more on that raga.

– The intent here, as in the earlier commentaries, is to flesh out the raganga and illuminate the major highways in the raga. It is not my intention to take you down every little bylane and clutter the page with stultifying detail. Several Sarang prakars disclose superficial variance across gharana and regional borders as the clips will testify. I do not propose to remark on every idiosyncrasy contained in a rendition. The assumption is that the curious reader will be motivated to further this inquiry on his own.

Raga Sarang

Raga Sarang is today considered the flagship raga of raganga Sarang. It is also known as Brindavani Sarang, a pointer to its popularity in the Mathura region.

Throughout this causerie M = shuddha madhyam and m = teevra madhyam.

The kernel of raganga Sarang is embedded in the following tonal cluster:

R M P (M)R, n P M R, S

Specializing it to Brindavani Sarang, we have:

N’ S R, R M R, (S)N’ S

In Madhmad Sarang, N is replaced by n.

The key idea above – and every Sarang wears it on its sleeve – is the treatment accorded to rishab. The R here is always sthira – i.e. unoscillated, not andolita – and independent. It is the vadi, and assumes the role of nyasa swara in both the ascending (arohi) and descending (avarohi) movements. This is later demonstrated tellingly by Pandit Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang.”

The nominal aroha-avarohana set for Brindavani Sarang is:

S R M P N S”::S” n P M R S

A sample chalan may be stated:

S, N’, N’ S R, P (M)R, n P M R, N’, S

Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang” and Shubha Mudgal

The prayoga of shuddha nishad in ascent and the komal nishad in descent separates Brindavani Sarang from Madhmad Sarang although they share the rest of the raga-lakshanas. In some old dhrupad compositions, shuddha dhaivat is occasionally and modestly (alpa-pramana) sought in a few in avarohatmak phrases, either as a kan (grace) to komal nishad or as a vivadi.

All the traditional prakars of Sarang are derivatives of the central theme outlined above. A measure of Sarang-anga is observed in other important raga families, namely the Malhars and the Kanadas. As always, in ragadari music, territorial integrity and identity are established and defended through appropriate swara-uccharana and raganga bheda.

Pandit Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande‘s exegetic work Hindustani Sangeet Paddhati gives a detailed account of the Sarangs. He remarks on the confusion prevailing in the early 20th C apropos of Brindavani and Madhmad Sarang, the bone of contention being the two nishads. The prevailing consensus awards to Brindavani Sarang both nishads and to Madhmad only komal nishad. This completes our preamble of the Sarang basics.

Earlier, the connection of the Sarangs with folk music was asserted. Now we present evidence in the form of audio clips. The gestalt of the raganga comes through very well even in these ‘light’ melodies. The encounters later segue into the demesne of classical proper.

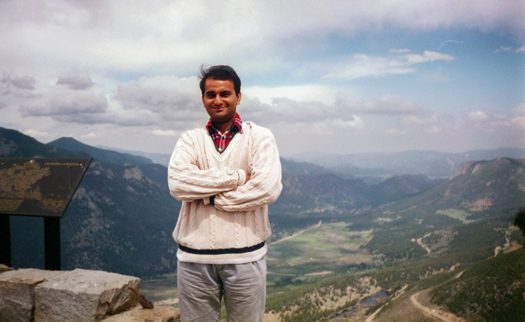

Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande

The choice for our opener is automatic. A late 1920s collector’s item of the Indian national song Vande Mataram rendered by Vishnupant Pagnis.

Lata Mangeshkar’s felicity with the Sarangs is consummate, as witness the following sequence of gems. This RANI ROOPMATI (1959) bandish reveals her extraordinary talents. Music: S.N. Tripathi, Lyrics: Bharat Vyas: aaja aaja bhanwara.

Film: SANSAR (1951); Music: Emani Shankar Sastry, M.D. Parthasarathy, B.S. Kalla; Lyrics: Pandit Indra: pyara munna humara.

The dulcet tones of Kishore Kumar and Lata Mangeshkar in QAFILA (1952). Music: Husnalal-Bhagatram: lehron se pooch lo.

Film: BHABHI (1957); Music: Chitragupta; Lyrics: Rajinder Kishen: kare kare badara.

Film: NAGIN (1954), Music: Hemant Kumar; Lyrics: Rajinder Kishen: jadugar saiyyan.

Who better than O.P. Nayyar to represent the folk music of Punjab which draws liberally on the Sarangs? An Asha-Rafi romp from KASHMIR KI KALI (1964); Lyrics, S.H. Bihari: hai re hai.

Another Punjabi contribution by the Punjabi diva Noorjehan: ha’ye dilbar dildara.

From an earlier era springs this beautiful number by Khursheed in TANSEN (1943). D.N. Madhok‘s lyrics are worked on by master tunesmith Khemchand Prakash: ghata ghanghor.

Uma Devi (better known as Tun Tun) in CHANDRALEKHA (1948). Music: S. Rajeshwar Rao, Lyrics: Pandit Indra: mana bhavana.

Bade Ghulam Ali Khan

RANI ROOPMATI was a Sarang orgy of sorts. Rafi and Lata: jhananana jhan.

Another vintage number by the Punju songstress Surinder Kaur. The film, SUNAHERE DIN (1949), Lyrics, D.N. Madhok, Music: Gyan Dutt: tum sang akhiyan lagake.

We conclude the Sarang folkfest with the popular Rafi-Asha number from DIL DIYA DARD LIYA (1966), tuned by Naushad to Shakeel Badayuni‘s words: sawan aaye ya na aaye.

Each of the preceding clips reveals a rustic facet or two about Sarang.

The classical league kicks off with Bhimsen Joshi‘s rendition of the traditional dhrupad-anga composition: tum raba tum saheb tum ho kartara.

R. Fahimuddin Dagar‘s authoritative presence is felt in this dhrupad despite the poor audio quality.

A composition of Aftab-e-Mausiqui Faiyyaz Khan (“Prempiya”) flawlessly executed by Basavraj Rajguru: sagari umariyan mori.

Among the great Gwalior masters of the early 20th C was Ramkrishnabuwa Vaze. Very little of his life is documented, as is the case with many Indian greats. In the West, utter mediocrities are often enshrined in biographical tomes. Indians, on the other hand, are content with doodling a silly sketch or two in a pamphlet. This state of affairs can be easily remedied by inculcating in Indian children the Western habit of never letting lack of knowledge and study get in the way of writing books.

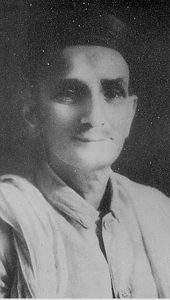

Ramkrishnabuwa Vaze

Vazebuwa brought to his gayaki certainty and attitude. Both are on display in this scintillating tarana.

Sarang has migrated southwards and is quite popular with the Carnatic musicians. Flautist K.S. Gopalakrishnan.

Raga Madhmad Sarang

Madhmad Sarang has much the same rights as Brindavani Sarang for the cachet of “Raganga Raga.” Almost all its lakshanas are identical to Brindavani, the difference being in the nishad: Madhmad takes only the komal nishad. In Carnatic music, Raga Madhyamavati shares the same scale.

The Madhmad spirit pervades this immortal S.N. Tripathi composition from RANI ROOPMATI. Those were the days when composers intimately knew the ropes of their metier. Mukesh: aa laut ke aaja mere meet.

We come to the most important clip of this article from the point of view of understanding the subtleties of raganga Sarang. This exposition by Pandit Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang” also touches upon the provinces of Kanada and Malhar. What separates Madhmad Sarang from the scale-congruent Megh is clearly demonstrated as are the points of difference between Megh and Megh Malhar. Jha-sahab holds forth for over 12 uninterrupted minutes and accomplishes what no reams of the written word can. Those handicapped by language will do well to seek translation of the proceedings.

The swarasmith par excellence, Bismillah Khan.

Patiala’s Fateh Ali Khan.

Among the greatest of the great masters, Bade Ghulam Ali Khan.

Kumar Gandharva with his own charming composition.

Two virtuoso displays from Jaipur-Atrauli conclude the Madmadh Sarang round.

L’enfant terrible Kishori Amonkar.

Bismillah Khan (from I&B Calendar 2005)

Mallikarjun Mansur‘s superb performance in an unpublished concert recording.

Raga Shuddha Sarang

This is probably the most popular Sarang prakar on the concert circuit today. It employs both shuddha and teevra madhyam. The shuddha nishad is allocated a vital nyasa sthana in the mandra saptaka. A large number of compositions place their sam on this lower nishad. The komal nishad is either eliminated or accorded a diminished role, usually in an avarohi sanchari either tied to shuddha dhaivat or in a declining n P M R movement. The teevra madhyam figures primarily in arohi passages. The avarohi slide m–>M is pleasing.

Encapsulating the above thoughts and recalling the Saranga-anga lakshanas lead to the following tonal summary:

– S, N’ S R, R M R, S N’, P’ N’ D’ S, N’ R, S

– R M R, m P, P R M R, S N’, N’ S R, S

– N’ S R M R m P, R m P N, (D)P, P N S” R” S”, R” S” N (D)P, R M R, M R (S)N’, N’ S

PRIVATE SECRETARY (1962) features a lovely Lata Mangeshkar solo executed to near perfection. Music: Dilip Dholakia, Lyrics: Prem Dhawan: sanware aaja pyara liye.

Kishori Amonkar

A take-off on the popular Shuddha Sarang mukhda found in traditional bandishes such as ja re bhanwara door or Faiyyaz Khan’s ab mori bata is seen in this CHANDI KI DEEWAR (1964) song. The music is by N. Datta (a vast Bong conspiracy to shamelessly claim this gifted fellow from Goa as their own was fearlessly exposed some years ago) and lyrics are by Sahir. Talat, the patron saint of losers in love, teams up with Asha: lage tose naina.

Kumar Gandharva

Mohammad Rafi, Chitragupta, Majrooh come together in NACHE NAGIN BAJE BIN (1960), in this the final item in our ‘light’ round: leke sahara tere pyar ka.

Jha-sahab‘s composition is set to Roopak tala and locates the sam on the uttaranga shuddha nishad: dharani dharo.

Padmavati Shaligram sings the lovely Atrauli-Jaipur issue, E tapana lagi gaili so balma mora.

Basavraj Rajguru works with a traditional bandish: ja re kagawa.

Shuddha Sarang is synonymous with the cheez, ja re bhanwara door, rendered here by Hirabai Barodekar.

This Bismillah cracker delights both mind and soul.

Vijay Raghav Rao‘s flute brings a change in tone colour.

The final item by Bade Ghulam Ali Khan will linger on in the mind.

Raga Miyan ka Sarang

Legend attributes this variant to Tansen, whence the name Miyan ka Sarang. One viewpoint has it that the raga obtains by eliminating komal gandhar from Miyan Malhar and by advancing the Sarang raganga. Miyan Malhar contributes the following tonal molecules:

n D, n D n M P

n D N, S or the slide N n (D)P.

The rest of the lakshanas hew to the Sarang line.

Hirabai Barodekar

These ideas are implemented in Jha-sahab‘s vilambit composition: sira raje mora mukuta.

Jha-sahab delivers a traditional composition addressed to ‘Rangile’: palaka na lagi rahi.

The final item in this triple header is Ramrang‘s own composition, jab Hari hath liyo, with the text describing an incident from the Lanka kand of the Ramayana.

Basavraj Rajguru tweaks the old dhrupad composition, dayanidhi, for a khayal assay.

Jaya jaya Rama japa nama, sings S.N. Ratanjankar, his own composition in Jhaptala.

The final selection in Miyan ka Sarang by Ali Akbar Khan is unorthodox and diverges significantly from the earlier clips. This version uses Shuddha Sarang, rather than Brindavani, for its base. It is curious that the version taught to Bhatkhande by Wazir Khan is nothing like this. The implication is that Allauddin Khan must have gotten Miyan ka Sarang elsewhere, not from Wazir Khan. Bhatkhande mentions that another Rampur ustad independently taught him Miyan ka Sarang which was identical to Wazir Khan’s, so the latter peddling an ersatz version to Bhatkhande can be ruled out in this instance. Furthermore, Bhatkhande’s alert and extraordinarily sharp mind was not easy to dupe. In most instances when the ustads played foul with the words of a bandish, or with ragas, he knew he had been lead down the garden path. He would have chased Wazir Khan like he would a rat through the Tundra and indeed he did so on more than one occasion, forcing the ustad to out with the truth or to plead ignorance. The case of Bahaduri Todi makes interesting reading in this context but that is a story for another day. I should mention that whenever someone appears in less than favourable light in these encounters, especially his gurus such as Wazir Khan, Bhatkhande does not directly mention them by name but makes oblique references. How one wishes there were independently documented accounts of these encounters. Bhatkhande, always self-effacing in his writing, must have left unrecorded many a fascinating story.

S.N. Ratanjankar

Alubhai Khan, the (naked) Emperor of San Rafael.

Raga Samant Sarang

The approach to shuddha dhaivat and its assimilation in vakra prayogas is the definitive theme in Samant Sarang. Typically such sangatis include tonal sentences of the type:

R M P, M n D P

R M P n D P

RMPDnDPM R

R M R, M D P

Some folks employ both nishads, others have use for only komal nishad. There is an occasional avirbhava of Desh. Although Soor Malhar is an allied raga swarawise it casts its lot with raganga Malhar.

Jha-sahab‘s vilambit composition in dheema Teentala comes with an arresting mukhda that swiftly scythes to the raga’s core: hamari sudh kahe bisari Udho.

Ramrang‘s breezy cheez: mandara more aayo sanwariya.

Ravi Shankar presents the Maihar viewpoint.

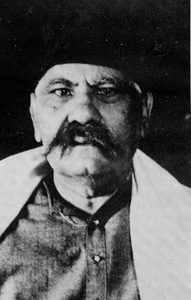

“Aftab-e-Mausiqui” Faiyyaz Khan

Faiyyaz Khan‘s alap in Samant Sarang.

Raga Badhans (Badhamsa) Sarang

This Sarang prakar comes in at least 3 disparate flavours. We present a version where shuddha gandhar is introduced rather piquantly into the avarohi flow. To wit, n P G M R, N’ S R M P N.

Ramrang sings a traditional “Sadarang” composition.

Shaunak Abhisheki renders Jha-sahab’s composition: bharmayo mana mero ina sanwaro ne.

An old recording of Birendra Kishore Roychaudhri on surshringar discloses a slightly different interpretation, in particular the attack on shuddha gandhar.

Raga Lankadahan Sarang

This rather ‘small’ raga carries a pompous name. The idea here is the insertion of komal gandhar into the Sarang framework. Typically this is accomplished in the avarohatmak sancharis. The precise attack on komal gandhar varies and principally takes one of two modes: A Darbari-like g M R S or a Desi-like P R g R S. Still others posit a Jaijaivanti-inspired R g R cluster. Other gharana-specific details involve inclusion/exclusion of dhaivat, use of one/both nishad(s).

To round off, a rare recording of Vilayat Hussain Khan “Pranpiya” of Agra.

Raga Salang

This audav jati Sarang prakar is in a sense the obverse of Madhmad. That is, the komal nishad in the Madhmad contour is replaced by its shuddha counterpart here, viz., S R M P N. This makes it somewhat tan-unfriendly (recall that the komal nishad makes life easier in avarohi runs).

C.R. Vyas

C.R. Vyas with his own composition: aba to mori mana moorakha manva.

Raga Dhulia Sarang

This is an aprachalita prakar mostly found in the Agra armoury. Even among the various stems of Agra there is a difference of opinion as regards the raga-swaroopa. Like its Malhar counterpart, Dhulia Malhar, the version included here combines elements of Desh and Sarang.

In this Latafat Hussain Khan recording, there is a fleeting, albeit discernable, touch of shuddha gandhar. It enters the picture via a M-G-R meend or via RG S R M P or through a quick RGM type of flourish.

Raga Saraswati Sarang

As the name suggests, Raga Saraswati is accommodated in the Sarang framework in this vichitra veena solo by Gopal Krishnan.

Raga Ambika Sarang

This raga was designed by Chidanand Nagarkar. The gandhar is rendered varjya, and elements of Shuddha Sarang and Kafi are blended together in a delicious cocktail. There are occasional reminders of Raga Saraswati but the presence of shuddha nishad and shuddha madhyam make for a clear separation.

Nagarkar’s composition is presented by C.R. Vyas: E ho bhanwara.

This completes our survey of the Sarang Family. We have touched upon all the traditional members of this group. More prakars exist but are either localized or have gone out of circulation. For example, Roshanara Begum sings Maru Sarang, which, if I correctly recall, uses the scale of Madhmad. I am not excited about that rendition although I may listen to it again one of these days just to refresh my memory. Then there is Noor Sarang which employs only the teevra madhyam. Parveen Sultana has recorded the hybrid Sarang Kauns. Bade Ghulam Ali Khan has left behind Hindoli Sarang. No matter what the fancy, a legitimate Sarang prakar must carry the germ of raganga Saranga.

Sir Vish Krishnan‘s assistance in compiling the ‘light’ segment is gratefully acknowledged.

Appendix

Raga Madhyamavati in the Carnatic paddhati shares its scale with the Hindustani Madhmad Sarang. Some selections of the Carnatic masters in Madhyamavati are offered here.

G.N. Balasubramaniam‘s alapana is followed by a Tyagaraja composition: Rama katha sudha.

M.D. Ramanathan‘s take on the same Tyagaraja composition.

Another rendition by M.D. Ramanathan, this time a composition of Shyama Sastry: Palinsu Kamakshi.

Finally, T.V. Sankaranarayana presents Papanasam Sivan‘s Karpagame.