by Rajan P. Parrikar

First published on SAWF on March 4, 2002

Part 1 | Part 2

Rajan P. Parrikar (Yosemite, California, 1989)

Namashkar.

Our exploration of Raga Marwa in the preceding monograph set the stage for an adjoining melodic domain: the Poorvi tract. Together, Marwa and Poorvi constitute two luminous precincts of Hindustani music’s vespertine repertoire. These central ragas, alongside their derivatives, form a web of complex, interconnected melodic threads, each contributing its unique lustre to the tapestry of Indian classical music. Today, we journey through the Poorvi Province, an odyssey both intellectually engaging and emotionally fulfilling.

Throughout this discussion, M = shuddha madhyam and m = teevra madhyam.

The Poorvi-Pooriya Dhanashree-Paraj-Basant Axis

Poorvi stands as a multi-faceted entity in the Hindustani tradition: as raganga, as raga, and as that. Its that corresponds to the 51st Carnatic melakarta, Kamavardhini, and comprises the swara set: S r G m P d N. The substitution of komal dhaivat for teevra dhaivat in the Marwa that introduces an entirely new aesthetic ecosystem. While the Marwa suite — anchored by Marwa, Pooriya, and Sohani — deliberately excludes the pancham swara, Poorvi integrates it with judicious artistry. Here, the gravitational pull of komal dhaivat bestows pancham a pivotal role, anchoring the melodic architecture of most Poorvi-aligned ragas. However, momentary omissions (langhan alpatva) of pancham are deftly interwoven into key phrases, creating a tension and release that underscore the Poorvi that’s dynamic essence. Yet, as with all things Hindustani, rare exceptions persist, challenging and expanding the raga grammar.

The ragas of the Poorvi that can be broadly categorized into two sub-classes, shaped by their anga lineage: the Shree-anga ragas and the Poorvi-anga ragas. The gravitas of Raga Shree has been explored earlier. In this installment, we focus on delineating the defining lakshanas of the principal Poorvi ragas while bringing their gestural subtleties into sharp relief.

The lakshanas of Raga Poorvi are considered first.

S, N’ S r G and N’ r G

The shadaj may appear in the skipped mode. The development gravitates towards gandhar in either direction, as we shall shortly see.

G r G m P, P m G, r S N’ S r G

With the right uccharana these poorvanga clusters are sufficient to establish Poorvi.

N’ S r G, r M G, Gm P, d, P m G M (r)G, r (G)M G

This tonal phrase packs a lot of ‘Poorvinformation.’ The peculiar behavior of shuddha madhyam comes into play here and dispels any incipient ideas of Pooriya Dhanashree. Take stock of the two different modes of approach to shuddha madhyam (it will be seen later how uccharana and chala bheda keep Poorvi distinct from Paraj on this score). The gandhar comes in for special treatment. Note, for instance, the kan of r in the M-laden cluster.

m d S” and m d N, N S”

These tonal phrases are employed in the uttaranga launch. Although pancham is an important nyasa swara it may be rendered langhan alpatva in either direction.

S”, N S”, r” N d, P

A crucial tonal sentence found in several ragas of the Poorvi that, notably Pooriya Dhanashree and Shree. The uccharana of r” N d P for the Shree-anga ragas assumes a distinct meend.

P, m P d m G r S r G

The bridge that ties together poorvanga and uttaranga tonal traffic.

Putting it all together we formulate a chalan:

S, N S r G, m G r G r (G)M G, r G m P, d m P m G M (r)G;

m d N S”, S”, N r” N d, P, d m G M (r)G, r S N’ S r G

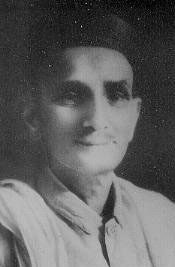

Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande

We now move to Raga Pooriya Dhanashree which is all the go these days and has elbowed Poorvi out from the concert stage. This raga retains most of the lakshanas of Poorvi sans the shuddha madhyam. However, while Poorvi is gandhar-based, the breath of Pooriya Dhanashree’s life is pancham. Accordingly, most of the tonal activity is centred around that swara. A couple of other additional lakshanas merit mention since they encase the raga signature, to wit:

P, m G m r G, P

The reiteration of G m r G is a sine qua non and the concluding hook-up with P from G as shown is recommended to establish the dominance of P. The arohi prayogas in Pooriya Dhanashree are almost always via N’ r G m P whereas in Poorvi N’ S r G is also admitted.

Obiter dictum: On the subject of of nomenclature, Pandit Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande conjectures that when the erstwhile Kafi-that Raga Shree branched into a Poorvi-that Shree, a similar transformation in its janya Raga Dhanyasi may have given rise to a counterpart Dhanashree, which, on account of its Poorvi-that affiliation, took on the moniker “Poorvi Dhanashree,” finally settling into “Pooriya Dhanashree.”

Next in line, Raga Paraj.

This is an uttaranga-pradhana raga with tonal activity clustered around tar saptaka shadaj. In the poorvanga there are two madhyams, like Poorvi; the distinction lies in uccharana and chalan bheda. The uttaranga has a superficial resemblance to Basant that may confuse the casual ear. The melodic trajectory in Paraj hews to the Kalingada line while retaining its Poorvi-that swaras. Sometimes the two are fused together and performed as “Paraj-Kalingada.” Let us develop the raga heuristically:

P, Pd Pd mP, (m)G M G, m G r S

The intonation of the M-laden phrase is direct without intermediary kans (cf. Poorvi). The Kalingada chalan can be retrieved from the above by replacing m with M. Sometimes an explicit G M P M G is also taken.

md md N, N S” N d S” N

Again, a likeness of Kalingada surfaces (there we have only shuddha madhyam and Pd replacing md). The elongation of N in S” N d S” N is a Paraj signpost.

S” N d P, G m d S” N, N S”r” S”r” N S” N d S” N

The dhaivat is rendered durbal throughout.

Paraj is a chanchal prakriti raga. Additionally, the recommended arohi locus forgoes rishab, as in N’ S G m d N.

We come to the final constituent of the Poorvi quartet – Raga Basant.

Like Paraj, Basant is an uttaranga-pradhana raga. The difference lies in its chalan and uccharana, and its drawing on portions of the Shree-anga. There are also special sangatis that are uniquely Basant. The following tonal sequence captures its essence:

m d r”, S”, r” N d P, [P] mG m->G, m G r S

The first half of this chalan derives its uccharana from Shree. It is meend-laden and gambheer in prakriti. Note the jump from d to the tar saptak r”. The second half begins with the square-bracketed pancham which denotes a shaken (and stirred) swara. The molecule [P] mG m, G where the first m is quick and the second elongated is sui generis to Basant.

d N r” N d P, G m d N m, G, m d G m G, m G r S

The r” N d P is Shree-inspired. Note, however, that the critical lakshanas of Shree – the strong rishab and the r-P coupling – are absent in Basant. The rishab, in fact, is skipped in arohi sancharis. The G m d N m and m d G m G are redolent of Pooriya gestures albeit with komal dhaivat.

m G r S, S M, mMG, N d P

The shuddha madhyam is not required in Basant but is often included as an additional artifact for raga bheda. It appears in a small Lalitanga cluster in the manner indicated above.

That completes our prolegomenon of Poorvi based melodies. These ragas are so pregnant with nuance that they can scarcely be described adequately through the written word. Nevertheless, it is hoped that some flavour of the melodic depth, ingenuity and the power of raga has been conveyed. In practice the lakshanas of ragas are burnt into a musician’s mind through taleem and, in the case of the ‘higher’ musician, through ceaseless reflection (manan-chintan).

In the opening clip, Pandit Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang” discursively ranges over the Poorvi terrain for 18 masterful minutes. This is by a long chalk the finest exposition on the topic there is. He addresses both shastra and its praxis, adducing traditional compositions to fortify the development. At one particularly poignant moment around 9:30, he briefly recites a lakshangeet of Raga Basant composed by Pandit Bhatkhande and extols the Chaturpandit’s drishti.

The audio selections to follow are the pick of the basket, many of them unpublished. It is left to the reader to discern the fidelity to or the extent of departure from generally accepted lakshanas.

Raga Poorvi

‘Light’ items adhering strictly to Poorvi are not common. From MEERA (1979), Ravi Shankar‘s music and Vani Jairam‘s voice: karuna suno Shyam mori.

A traditional vilambit khayal by Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang”: tonama he ma’i.

This druta jod-bandish is Jha-sahab‘s own: kavana mantra tantra.

Faiyyaz Khan

Aftab-e-Mousiqui Faiyyaz Khan‘s alap makes a masterful statement.

Faiyyaz Khan‘s 78 rpm rendition: Mathura na ja re.

The Gwalior platoon is in full strength.

Sharatchandra Arolkar gives us the traditional piyarva more in Tilwada tala. Notice the exquisite meend from m to M at around 1:49.

Yashwantbuwa Joshi: piharva ki base tu mohe.

Ghulam Hasan Shaggan‘s rendition contains an explicit chromatic use of the two madhyams: sukha sampata.

A traditional bandish in vilambit Jhoomra by Shaila Datar: Dilliya nagarwa.

Mogubai Kurdikar dwells on a Sadarang cheez: aavana kahi.

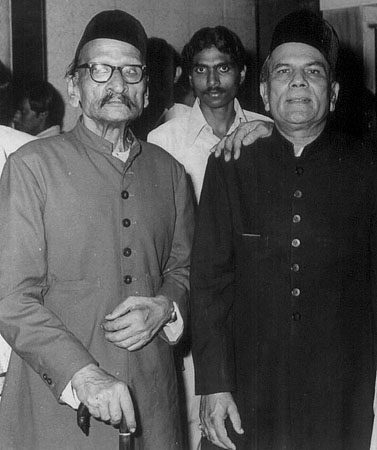

Thirakhwa and Azmat Hussain Khan (r)

The same bandish is developed by Azmat Hussain Khan who had his feet in both the Atrauli and Agra schools.

Another Atrauli-Jaipur confrere, Padmavati Shaligram, plies a well-known traditional composition: kagava bole.

Radhika Mohan Moitra is considered one of the most influential musicians to come out of Bengal. He developed a style of sarod that is complementary to that of the Maihar turkey Allauddin Khan. We join him at the beginning of his jhala.

Poorvi is sometimes rendered with a shuddha dhaivat particularly in Bengal as witness this Tagore composition by Suchitra Mitra.

This concludes our Poorvi excursion.

It is a pity that such a profoundly beautiful melody has been cast off by most performers of the day. En passant, Bhatkhande observes that some tantrakars, especially from Rampur, regard the dhaivat in Poorvi as ‘chadhi‘ (raised). This is, of course, a matter of individual or stylistic choice.

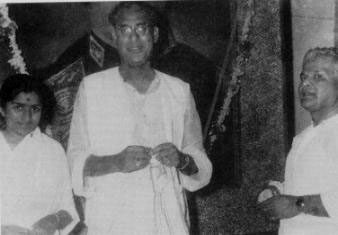

M.S. Subbulakshmi, Alladiya Khan

Raga Pooriya Dhanashree

There is no better vehicle available to the bathos-stricken than Raga Pooriya Dhanashree. The raga finds employment in all genres.

Jitendra Abhisheki recites from the Bhagavad Geeta.

M.S. Subbulakshmi‘s Dashavatara Stotram is set to music by K. Venkataraman.

Koyaliya uda ja, sings the perennially lorn Mukesh.

Amir Khan‘s rendition in BAIJU BAWRA (1952). All composer Naushad probably did was arrange for the ustad’s breakfast: tori jai jai.

(L-R): Lata, Amir Khan, Vasant Desai

Asha Bhonsle‘s jeevalaga is held up by Marathi dingbats as the biggest pimple on the musical face of Maharashtra. The composition by Hridaynath is C-grade but that is sufficient to send the ghats and their lapdogs, the Goans, into raptures. The Shree-anga comes on so strong that I have reluctantly included the song here in this section. There’s a soupçon of Gouri, too.

Asha‘s next effort is a knock-off by composer Roshan on a famous cheez (readers will recall Lakshmi Shankar’s recording). From SOORAT AUR SEERAT (1962): prema lagana.

Two non-film tunes by Khaiyyam in Mohammad Rafi‘s voice:

Gangubai Hangal

From SAMPOORNA RAMAYANA (1961), Lata sways gently to Vasant Desai‘s baton: ruka ja’o.

We repair to the classical lounge.

The lakshanas emerge beautifully in Gangubai Hangal: araja suno.

The same bandish is handled by Gangubai’s guru, Sawai Gandharva. The discriminating listener will at once see how these voices carry in them the imprimatur of anubhava.

Kumar Gandharva sings his own compositon, bala gayee jyot.

Sawai Gandharva

From the unpublished files of Bade Ghulam Ali Khan.

This section concludes with Kesarbai Kerkar. The label on HMV mistakenly has it as Pooriya Dhanashree. The key Pooriya Dhanashree lakshanas are nowhere to be seen. And notice the two dhaivats. This is a type of Gouri. See On Raga Lalit-Gouri for a rendition of the same bandish by Abdul Karim Khan in the Marwa-that Gouri. Be that as it may, a glorious display: ati prachandana.

Raga Paraj

Vasantrao Deshpande sets the Ganges on fire with this delightful live performance. The vilambit is the traditional laal aaye ho followed by pavana chalata. Zakir Hussain of San Anselmo is on the tabla.

Vasantrao’s druta cheez, pavana chalata, was composed by “Sanadpiya,” the colophon of Tabaqqul Hussain Khan of Bareilly who was employed at the Rampur court. Pandit Bhatkhande collected and documented several compositions from him. Thakur Jaideva Singh writes in his book, Indian Music: “…[Sanadpiya’s] thumaris were based mostly on instrumental pieces (gatas) which he heard from the instrumentalists of Ramapura. So they strike the listener like instrumental pieces rendered in bolas (wordings). Such thumaris in madhya laya (medium tempo) are known as Bandhana or Bandisa-ki- thumari or Bola-banta-ki-thumari. Their beauty lies mostly in their dance-like rhythmic effect…”

Paraj’s uttaranga-pradhana mien is underscored in the Atrauli-Jaipur interpretation which dispenses altogether with the shuddha madhyam.

Mallikarjun Mansur: akhiyan mori laga rahi.

The same composition in Kesarbai‘s imperious gayaki.

Mushtaq Hussain Khan

Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, too, has no use for shuddha madhyam but he comes close to treading on Basant’s toes: lataka chalata.

The Rampur-Sahaswan view by its distinguished exponent Mushtaq Hussain Khan.

Agrawale Vilayat Hussain Khan sings the cheez we heard earlier from Vasantrao – pavana chalata. It is curious that Vilayat Hussain’s antara attributes it to one “Alampiya” whereas Bhatkhande has credited it to “Sanadpiya.”

There is no doubt whatsoever of the authorship of the next bandish. Faiyyaz Khan treats the celebrated composition of “Saraspiya” (Kale Khan of Mathura): Manmohan Brij ko rasiya.

Ravi Shankar

We wrap up with Ravi Shankar.

Raga Basant

The familiar song by Bhimsen Joshi from BASANT BAHAR (1956) composed by Shankar-Jaikishan: ketaki gulaba.

The tans of Dinanath Mangeshkar were the musical equivalent of a Disneyland joyride: precipitous and thrilling. Here he is with a composition of Sadarang: aba rtu.

Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang” in an enchanting mehfil.

Dinanath Mangeshkar

This unpublished edition of Basavraj Rajguru finds him in fine feather. The traditional khayal composition of “Manrang,” nabi ke darbar, is followed by the well-worn phagava braja dekhana ko.

A traditional composition, panaghatava thado ma’i, by Krishnarao Shankar Pandit.

A rare recorded instance of Abdul Karim Khan dealing a bada khayal.

The motivated reader may at this point reflect on the points of distinction between Paraj and Basant, armed that he is now with actual renditions.

Pannalal Ghosh was indisputably the greatest flautist of our times.

We bring the curtain down on this segment with Bade Ghulam Ali Khan who blends Hindol and Basant in this mehfil.

In Part 2 we range over several derivative ragas of the Poorvi that.

Part 1 | Part 2