by Rajan P. Parrikar

First published on SAWF on February 18, 2002

Part 1 | Part 2

Rajan P. Parrikar

Photo: Sanjeev Trivedi

Namashkar.

The thought of Raga Marwa stirs memories of many youthful evenings spent walking on the Miramar beach in Panjim, bouncing Amir Khan’s stupendous opus in the corridors of my mind. Lost in the intoxicating reverie wrought by music and colourful sunsets, I occasionally allowed myself the fantasy of imagining what it might be like to feel and see raga from the Himalayan heights of an Amir Khan. I wondered if that great man, too, had likened himself to “a boy playing on the sea-shore, diverting myself in now and then finding a smoother pebble or a prettier shell than ordinary, whilst the great ocean of raga lay all undiscovered before me.” After sundown I would walk home to a hearty meal and then hit the sack. For those were the days when we took pride in leisure. How times have changed. Today people take pains to disclose just how “busy” they are, as if it is a badge of achievement. You’d think they have been charged with re-designing God’s floor plan for the universe. [Update: I am delighted to hear that this “pompous” introduction has given some folks piles. As always, I aim to annoy and offend.]

In this installment devoted to the Marwa group, we will examine its familiar members and unveil some of the lesser known affiliates. A companion feature to follow soon will be devoted to the citizens of the Poorvi Province.

Throughout this discussion, M = shuddha madhyam and m = teevra madhyam.

The Marwa-Pooriya-Sohani axis

Marwa is among the ten thats enumerated by Pandit Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande and is characterized by the swara set S r G m P D N corresponding to the Carnatic melakarta Gamanasrama. The flagship raga of this that – Raga Marwa – drops the pancham altogether. The same is true for two other principals of this group – Pooriya and Sohani. These three ragas maintain a collegial but distinct melodic dynamic. It is therefore instructive to view them together under the same lens. This is a marvelous example of the magic of raga music – the evolution of differences originating from the same scale-set through the agency of chalan bheda (differences in melodic formulation), uccharana bheda (differences in intonation of swara) and vadi bheda (differences in relative emphasis of swara). Facility in this kind of sport demands cultivation of appropriate habits of mind and manana-chintan (reflection). But the game is well worth the candle for the ananda it brings.

The main idea in Raga Marwa is the overwhelming dominance of r and D. This is an apavada since no consonance exists between r and D; it took some genius sense this germ of an idea and fructify. The definitive tonal sentences are:

D’ N’ r G r, N’ D’, m’ D’ S N’ r, S

The points of note in this poorvanga construct are the nyasa on rishab and dhaivat, the langhan (skipping) of shadaj in both arohi and avarohi directions, and the alpatva (smallness/weakness) of N.

D, m G r G m D, D m G r

The madhya saptak movement. Marwa typically employs ‘khada‘ swaras – i.e. the lagav is direct and unwavering, shorn of delicacies and meends (the situation is different in the scale-congruent Raga Pooriya).

D N r” N D, m D N D S”

The uttaranga marker where the nishad is often skipped en route to the shadaj (Pooriya shares this lakshana, but not Sohani).

That was Marwa in a nutshell. It is an affective symbiotic relationship between r and D. Both the swaras are full-blown nyasa locations, yet bound to one another by an invisible cord: the pull of one is strongly felt when you visit the other.

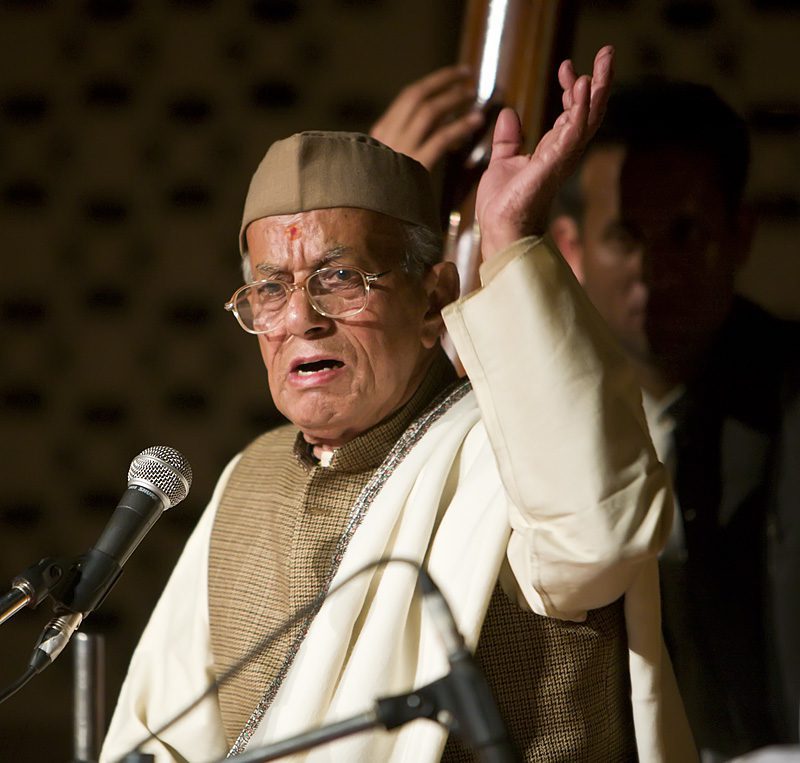

Ramrang at Ravi Shankar Centre, Chanakyapuri, Delhi (2007)

© Rajan P. Parrikar

We now prise open Raga Pooriya, an old raga with a swara locus identical to Marwa. Most generic accounts – childish, really, mostly by people who ought to have no business talking or writing on ragas – distinguish the two based on their vadi-samvadi pair: r-D in Marwa and G-N in Pooriya. It takes much more than this simple swap to realize a raga. Pooriya employs special sangatis to realize the G-N coupling. The lakshanas are:

N’ r G, G r N’ D’ N’, N’ m’ D’ S

The gandhar is advanced, both r and D recede.

G m D N, N (N)m, G; m D-G m G

This tonal phrase represents Pooriya’s prana and packs several key lakshanas: the dominance of G, the N-m coupling, and the D-G sangati. There is a measure of delicacy to the intonation.

G m D N D S”, N r” N (N)m, G, m D-G m G, r S

Although N is strong in Pooriya, it is, like Marwa, often skipped en route to S”. The swoop from N to m is delicious; sometimes it works in the obverse as well (N’-m).

Next in line, Raga Sohani.

The first-order difference here is that instead of the N’-r-G chalan employed in Marwa and Pooriya, the rishab is skipped and to yield a N’-S-G form. And unlike the other two, Sohani’s strength is vested in D and G. Then there are the special gestures. Sohani is an uttaranga-pradhana raga, its essence apprehended in the following sentence:

G m D N S”, S”r” S”r” N S” N D, N D-G m G

The nishad is a required conduit to the tar saptaka S”. As in Pooriya, the D-G sangati is also observed but the attack is markedly different. In Sohani the D-G prayoga is initiated from N whereas in Pooriya it is typically lauched from m. Attention to these minutiae is vital and cuts to the core of raga music. Great musicians instinctively recognize such bheda-bhava even though they may not have the requisite expository skills or the vocabulary to verbalize them.

Everything I have written above is superfluous, for Jha-sahab has magnificently distilled the essence of these three ragas and packaged it into 6 masterful minutes. We are privileged that someone of his background and calibre is still among the living, and fortunate that the technology now exists for bringing him to a worldwide audience.

Pandit Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang” on the Marwa-Pooriya-Sohani axis.

With that propaedeutic to build upon, it is time get our ears wet.

Lata Mangeshkar

Raga Marwa

Lata Mangeshkar‘s beauty from SAAZ AUR AAWAAZ (1966) composed by Naushad belongs to the ranks of the finest ‘light’ numbers based in this raga: payaliyan banwari baje.

This quasi-Marwa has been composed by K. Mahavir who comes from a long line of accomplished classical musicians. His father, Mahadev Prasad Kathak, was associated with Swami Hari Vallabh (after whom the famous annual sammelan in Jullunder takes its name). Lata Mangeshkar: sanjha bhayi ghara aaja.

Jha-sahab unveils his suite with a vilambit Roopak composition that at once reveals the cut of Marwa’s jib: joga le aaye tuma Udho.

Jha-sahab now explains the textual import, then sketches his elegantly designed cheez.

When Vasantrao Deshpande passed away, Bhimsen declared that Marwa had died in Maharashtra. Vasantrao’s winsome phirat and spontaneous delivery make this a classic.

Bade Ghulam Ali Khan wields an old khayal (documented by Bhatkhande) that places the sam on the mandra teevra madhyam: nanadiya chavava.

“Aftab-e-Mousiqui” Faiyyaz Khan‘s certitude in intonation expresses well the khada swaras of Marwa as witness this unpublished excerpt.

Anant Manohar Joshi aka Antubuwa, a disciple of Balkrishnabuwa Ichalkaranjikar (the man responsible for bringing khayal to Maharashtra), trained several musicians, among them his son, Gajananrao Joshi. This recording of archival value has an avartana or two of Antubuwa’s khayalnuma in Jhoomra tala followed by a traditional cheez attributed to ‘Rangile’, bolana bina kabahun (Note: Vasantrao sings this in druta Ektala, as documented by Bhatkhande).

The popular piya more anata des gai’lava is put through the paces by Atrauli-Jaipur’s Mallikarjun Mansur.

Bhimsen Joshi blends a soupçon of Raga Shree (mP–>r) into Marwa to haunting effect. There’s a cameo role for komal dhaivat (1:56 into the clip).

Ramkrishnabuwa Vaze

Jagannathbuwa Purohit “Gunidas” conceived this explosive cheez, delivered here by his pupil Jitendra Abhisheki: ho guniyana mela.

Abdul Karim Khan‘s tarana.

Ramkrishnabuwa Vaze‘s breezy manner is always a great pleasure.

What you just heard were very high quality renditions of Marwa. Now please wipe your slate clean. Of Shakespeare, Ben Jonson remarked, “He was not of an age, but for all time.” The same is true of Amir Khan‘s Marwa. It is not merely a performance. It is the ne plus ultra in meditation. What Einstein’s General Theory is to scientific thought Amir Khan’s Marwa is to musical thought. We must make do with but a snatch here. The traditional piya more anata des gai’lava in vilambit Jhoomra, followed by guru bina gyana na pave.

Raga Pooriya

Also known as Raat-ki-Pooriya, Pooriya’s lakshanas emerge resplendent in Bhimsen Joshi (recall Jha-sahab’s discourse on the subject). Right away in the opening movement we have the elongated N and the N-m sangati, eventually culminating on the sam via N’-r-N’-m’. Both are traditional compositions: Sadarang’s vilambit pyare de gara lagi and the druta cheez, ghadiyan ginata jaat.

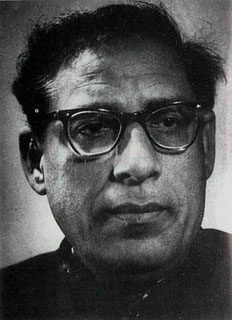

Amir Khan

Take stock of the D-G sangati embedded in GmD-Gm G within the first 30 seconds of this Amir Khan classic. Bhatkhande has documented this khayal: yare maula yala yalala le.

We have come to expect coups de théâtre from Omkarnath Thakur and he doesn’t disappoint. A traditional composition favoured by the Gwalior musicians, sughara bana.

D.V. Paluskar plies the selfsame sughara bana.

Digression: Bhatkhande’s documented notation for sughara bana shows the sam to be on rishab but the subsequent movement converges on mandra nishad. Recall that Amir Khan’s druta cheez in Marwa places its sam on mandra nishad but the melodic arrow points to dhaivat. Now, if ethnopimp A read Bhatkhande (remember that no ethnopimp has the ability and knowledge to understand much less critique Bhatkhande) he would conclude that the Chaturpandit didn’t know his Pooriya from Marwa and publish this ‘finding’ in an ethnoporn rag. Then, ethnopimp B will refer to A’s ejaculate and in a display of tautological genius declare it to be “seminal.” Both A and B will then be awarded tenure at their respective universities.

For the uninitiated, the ethnopimp calls himself “ethnomusicologist” and is found loitering in the music departments of universities in Western Europe, America and Canada. The racist term “ethnomusicology” (when did you last hear the music of Beethoven studied under “ethnomusicology”?) refers to the field infested by these worthless parasites masquerading as academics. There are PhD theses, careers and tenure to be had for the asking, for the benevolent Lord expressly created the “third-world” cultures to be a font of rich pastureland for the vultures inhabiting the humanities departments in the West.

Apropos of Indian music, the ethnopimp had once fancied himself as the intermediary between the ustad and the lay Indian masses, arrogating to himself the onerous task (the proverbial “white man’s burden”) of explaining to the Indians their own music. Never mind that the titmouse wouldn’t recognize swara even if it bit off his (or her) buttcheeks. Alas, things haven’t gone quite the way the ethnopimp had hoped. The newer generation of Indians decided it wasn’t going to play possum while the ethnopimp peddled his balderdash. Today, the ethnopimp lies in ruins, his family jewels shattered and his head combed at will by even Indian children.

En passant, as a pleasurable pastime, I propose that Indians fund a ‘research’ grant to study the ethnopimps and the twaddle they have excreted all these years. A few ethnopimps could be rounded up to be our lab rats. At the end of this study (which ought not to take long – the combined ‘knowledge’ of all ethnopimps put together can be had for a penny and you’ll get some change back) the poseurs can be officially certified for the sewer rats that they are. End of digression.

Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande

Reverting to the topic at hand, Bhatkhande‘s discourse on Pooriya contains a rare and telling display of emotion. Recall that his magnum opus Hindustani Sangeet Paddhati is in the form of a Socratic dialogue between pupil and master. At one point, Panditji recounts (my translation cannot quite convey the same effect as that in Marathi): “…Many years ago I heard this raga from a very famous Musalman gayak. Believe it or not, for a few moments I was lost to the world. You will not be able to imagine the magnitude of the effect that his music wrought on my person. Because you have not had that kind of anubhava yet and because you have yet to acquire the requisite depth in this field…”

Bhatkhande must be made compulsory reading for anyone setting out to write anything on Hindustani music. His work is, to put it mildly, “a feast of reason and flow of soul.” Finally, he was not a “musicologist” as is commonly cited by the uneducated. Bhatkhande’s work encompassed Music. He was a musician, a vaggeyakara, a shastrakara and a vidwan all rolled into one. He was also a visionary (that much molested word of the dotcom era) with a deep social conscience. “Musicologist” is suggestive of a relatively low-level activity. There is no need at all to seek recourse to inadequate foreign terminology, to describe a phenomenon the Western world is unfamiliar with, when several Indian terms serve the purpose admirably.

Vilayat Hussain Khan, accompanied by his son Younus Hussain Khan: pyara de gara lage.

A vigorous nom-tom inaugurates this rendition of “Aftab-e-Mausiqui” Faiyyaz Khan. His colophon “Prempiya” is heard in the antara: main kara aayi piya sanga.

An unpublished cut of Mallikarjun Mansur completes our survey of Pooriya.

Raga Sohani

This sprightly raga is an instant pleaser much like that buxom leotard-wrapped babe at your local gym that you lust after while pretending to work out (by way of comparison, think of Marwa as your mother-in-law: solid, ponderous and unfunny). The Carnatic equivalent of Sohani is Hamsananda.

The SUVARNA SUNDARI (1957) number set to music by Adi Narayana Rao is a perennial favourite. Lata Mangeshkar and Mohammad Rafi: kuhu kuhu bole koyaliya.

Another old classic, from SANGEET SAMRAT TANSEN (1962), tuned by S.N. Tripathi for Mukesh: jhoomti chali hava.

Jitendra Abhisheki

From GRIHASTHI (1963), music by Ravi, Asha Bhonsle‘s voice: jeevana jyota jale.

Composer and singer of this beautiful Marathi bhajan: Jitendra Abhisheki.

That much of Sohani’s activity is uttaranga-based should be evident by now.

Moving along, Jha-sahab sketches a traditional cheez: bari bari ja’oon Murari.

The movie MUGHAL-E-AAZAM (1960) featured a rendition by Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, patterned after the well-known thumri, prema ki mari qatara: prema jogana bana.

BGAK’s unpublished Punjabi bandish.

Kumar Gandharva‘s fetching composition is delivered with his customary verve: ranga na daro Shyamji.

Bismillah Khan, the swarasmith par excellence, weaves his magic.

The final entry in the Sohani catalogue is the sankeerna Raga Sohani-Pancham. As the name suggests, the raga blends elements of Raga Pancham (see On Raga Bhatiyar) with those of Sohani. The motivated reader is invited to figure out the dynamic.

Vilayat Hussain Khan “Pranpiya”: sakhi mori.

Bade Ghulam Ali blesses Lata

Raga Bibhas (Marwa that)

Bibhas has cast in its lot not with one but with three thats – Bhairav, Poorvi and Marwa. Even within each that it has spun off subsidiary versions. The audav-jati Bibhas of the Marwa that – S r G P D – is the most popular. D and r dominate the proceedings although pancham is another important nyasa location. Oftentimes, r is rendered durbal or even langhan alpatva (skipped) in arohatmaka prayogas. An avirbhava of Deshkar obtains in this formulation. The following sentence conveys the essence:

G P D, D, P G r, S (P)G P, D, P (S”)D S” r” S, D, P

The kans of m and N occasionally observed cause no injury to the raga-bhava.

Jitendra Abhisheki sings the popular composition, He Narahara Narayana, a creation of Pandit Bhatkhande. The original dhrupad composition has been adapted by the khayaliyas. Abhisheki stays textually true (almost) to Bhatkhande whose colophon ‘chatura‘ is cleverly wedged in the antara.

The lakshanas are clearly enunciated in this segment of Shruti Sadolikar. Attention is drawn to the strong dhaivat and the langhan of rishab in arohi sancharis.

Kishori Amonkar‘s Bibhas is an exemplar of sensitivity and subtlety in intonation. She singles out dhaivat for her shruti-play, toying with it, not explicitly advancing komal dhaivat but creating a deliberate abhas through delicate meends. Watch out for the first instance at 0.05 into the clip. Narahari Narayana, this time in Roopak tala.

A maverick version by Kesarbai Kerkar concludes this section. Catch the distinct teevra madhyam in the mandra saptak in S (D’)m’ D’ S at 0:17. Then comes a startling shuddha rishab in the tar saptak, viz., G”R”S” at around 0:53. There are more deliberate occurrences of this shuddha rishab in the tans following. The composition mora re is also heard in renditions of the Poorvi-that Bibhas.

Kesarbai and Dhondutai Kulkarni

Raga Jait

Jait has a degree of overlap with Bibhas but there are compelling differences. Consider the following chalan:

S G P G P, P DG P, P D P S”, S” r” S”, S”->P, P D G P, P G r S

P has now advanced whereas D is in the back seat. O the beauty of ragadari! The clusters P DG P and P D P S”, and the S“-P swoop are Jait’s signposts.

Vasantrao Deshpande

Jha-sahab recites the chalan and then sketches a composition.

Vasantrao Deshpande: kalasha jyoti lagi.

The Atrauli-Jaipur version is bi-rishab, a variant documented by (who else?) Bhatkhande. Observe the first instance of shuddha rishab at around 0:18 in Mallikarjun Mansur‘s hitherto unpublished excerpt.

The Rampur-Sahaswan vocalist Hafeez Ahmed Khan.

These five preceding ragas constitute a core from which most other Marwa-that melodies derive their genetic material. A study of these fundamental forms is sufficient to understand the rest the members of the Marwa Matrix since they are simply variations of the foregoing melodic behaviors. The rest of the elements of the matrix are discussion in Part 2.

Part 1 | Part 2