by Rajan P. Parrikar

First published on SAWF on September 16, 2002

Rajan P. Parrikar in Colorado Springs (1991)

Namashkar.

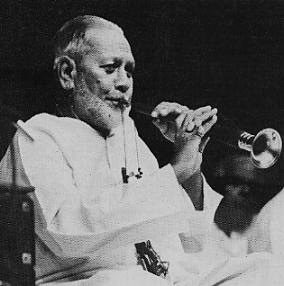

In this edition of Short Takes, we welcome the maha-raga Malkauns into our fold. This Bismillah Khan classic, a permanent fixture in the Indian musical imagination, never fails to dazzle and is fresh as new paint even today.

Our tour begins with a synopsis of the raga-lakshanas. The kernel of raganga Kauns is then distilled. The high class Malkauns selections that follow are a feast fit for the Gods. The latter half of this session features a portfolio of Malkauns derivatives.

Bismillah Khan

Throughout our excursion, M = shuddha madhyam and m = teevra madhyam.

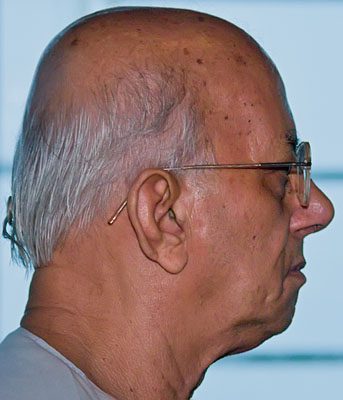

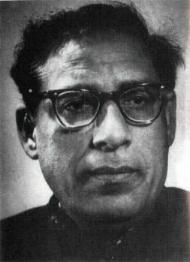

Raga Malkauns

The name “Malkauns” (cognates: Malkosh, Malkoshi, Malkans etc.) is said to derive from “Malava Kaushik,” an old melody that finds mention in ancient treatises such as the Sangeet Ratnakara of Sarangdeva. There is, however, no structural similarity between that Malava Kaushik and the present-day Malkauns. The current swaroopa of the raga is conjectured to be around 300-400 years old. The curious reader is referred to Pandit Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande‘s monumental work Hindustani Sangeet Paddhati where he traces the Malkauns trail. The Carnatic raga carrying the swaras of Malkauns goes by the name Hindolam.

Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande

The swara-set of Malkauns gives a wide berth to both R and P leaving behind an audav-jati (pentatonic) contour: S g M d n. In Pandit Bhatkhande’s taxonomic scheme the raga is placed under the Bhairavi that. Recall that certain gestures in Raga Bhairavi take after Malkauns. The signal characteristic of Malkauns concerns its nyasa locations: each one of its swaras is considered apposite for nyasa. No other raga has this attribute. The implication being, you cannot go wrong in Malkauns. With five locations available for nyasa, the vistar area extends far and wide, overcoming the limitations of a restricted tonal space inherent to pentatonic ragas. The key lakshanas of Malkauns are now encapsulated.

S, d’ n’ S, n’ g–>S, S g M g–>S

The sui generis meend g–>S serves as a vital constituent of raganga Kauns. The uccharaaa is crucial: g is rendered deergha before initiation of the meend. This precipitates the shanta-gambheera rasa characteristic of Kauns. The langhan (skipping) of n in the declining prayoga from S to d’ (or from S” to d) is another point of note.

d’ n’ S M, M d M, S g M g–>S

Although all the swaras are nyasa-worthy, the madhyam is considered primus inter pares, the centre of melodic gravity, as it were. Notice the leap from S to M, a Malkaunsian trait.

g M d n, M d n S” d n d–>M

Here we have uttaranga modus operandi. The d–>M meend is analogous to the poorvanga g–>S and serves as another artifact of the Raganga Kauns kernel; d is rendered deergha before the slide to M, again reinforcing the shanta-gambheera effect.

S”, d n S” g”, g” M” g”, n g”–>S

Attention is drawn to the n to g coupling, a key lakshana of Kauns raganga.

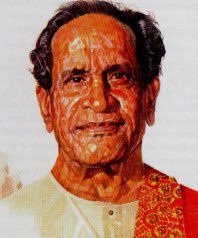

Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang”

© Rajan P. Parrikar

Obiter dicta:

(a) In the Malkauns progression there is samvad (consonance) between the S-M, g-d and M-n pairs.

(b) It is observed that some vocalists (well-known names among them) occasionally admit a higher value of n that falls within the penumbra of N, especially in the arohi prayogas. This practice appears to be inadvertent given the inconsistency and irregularity with which it occurs.

This completes our inspection of the Malkauns arena. Of course, the uccharana, vital in these matters, cannot be adequately conveyed through the written word.

Malkauns lends itself to varying degrees of interpretation and complexity. To the novice it presents a welcoming, friendly facade. To the vidwans and the masters, it reveals a compass as vast as the Serengeti plains, a lifelong melodic hunting ground in which to exercise and slake the creative daemon.

Who better than Pandit Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang” to eulogize Malkauns? His words in the second half of the clip lay bare his enormous love and feelings for this great raga. This riveting display was recorded over the California-Allahabad telephone line.

We now step into the Malkauns citadel. Although ‘light’ compositions in the melody are legion we shall make do with only a token few here.

In BADA AADMI (1961), Mohammad Rafi sings to Chitragupta‘s tune: ankhiyana sanga.

The 17th C saint Tukaram avers that he is smaller than an atom and as vast as the sky in a beautiful Marathi abhanga. Dilip Chitre‘s translation of this abhanga is available in Says Tuka (Penguin Classics).

Too scarce to occupy an atom,

Tuka is vast as the sky.

I swallowed my death, gave up the corpse,

I gave up the world of fantasy.

I have dissolved God, the self, and the world

To become one luminous being.

Says Tuka, now I remain

Only to oblige.

Bhimsen‘s delivery is in step with Tuka’s feelings: anuraniya thokada Tuka akasha evadha.

Bhimsen Joshi

In the Marathi drama RANADUNDUBHI (1927), Vazebuwa‘s tune is rendered by Dinanath Mangeshkar: divya swatantraya ravi.

We swing open the classical vaults with a performance of the Gundecha brothers. Their alap gives way to a dhrupad in honour of Lord Ganesha.

‘Aftab-e-Mousiqui’ Faiyyaz Khan weighs in with a magnificent dhamar.

Two selections of D.V. Paluskar follow. First, a vilambit khayal.

And Meerabai‘s immortal pada: pag ghungaroo baandha Meera nachi re.

Krishnarao Shankar Pandit deals the famous “Adarang” composition in vilambit Ektala: aaja more ghara aa’ila.

That composition of “Adarang” has been popularized by Amir Khan as a cheez in Teentala whereas Bhatkhande has documented it in druta Ektala. This is a good instance of a bandish morphing over time and across stylistic schools.

Kumar Gandharva laces his Malkauns with (at least) a couple of quaint touches. The measured g–>S meend emits an abhasa (impression, semblance) of the rishab. The reader is invited to figure out the second quirk (Hint: hear out his druta bandish).

Omkarnath Thakur offers the Gwalior staple: peera na jaani.

Omkarnath again in a dramatic rendition of the immensely loved pag ghungaroo baandha kara nachi re. His tweaking a key word in the mukhda (compare with D.V. Paluskar) is intriguing.

Bhaskarbuwa Bakhale in a mehfil; at extreme right is ‘Lokmanya’ Bal Gangadhar Tilak

The widely-performed Malkauns chestnut sasundara badana ke is a composition of Nawab Ibrahim of Tonk (whose colophon is imprinted in the antara). It was first popularized in Maharashtra by the Bhaskarbuwa Bakhale.

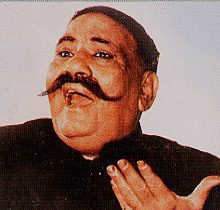

Here we have Bade Ghulam Ali Khan singing that bandish in this unpublished recording.

Another unpublished selection of Bade Ghulam Ali.

To round off the Bade Ghulam Ali Khan feast, his published classic: mandira dekha dare.

Bade Ghulam Ali Khan

Barkat Ali Khan (BGAK’s brother) was an outstanding musician but, alas, he had to live in the shadow cast by his giant of a brother. He, too, sings mandira dekha dare.

A couple of selections of Kesarbai’s empyrean artistry: maisana meeta.

Kishori Amonkar sparkles in this mehfil recording. Around 3:00 we find her reading the riot act to an errant calf.

Abdul Karim Khan

The bandish, peera na jaani, heard earlier in a vilambit gait is now presented by Abdul Karim Khan in druta laya.

Master Krishnarao‘s (Krishna Phulambrikar) is a restrained Malkauns: kaahun ki reeta.

The keys to the sanctum sanctorum in the Malkauns temple are given only to the great vocal masters. The ding-dongers have no place there although they are permitted to graze in the courtyard outside. With one and only one exception: Nikhil Banerjee.

Shridhar Parsekar (1920-1964), from the tiny village of Parsem in Goa, established himself as one of the great violin virtuosos of the day but died before his time. To know more about Parsekar, click here.

Shridhar Parsekar

When God created Malkauns, only two mortals were allowed the privilege of peeking over His shoulder while He was at work. Bhimsen Joshi and Amir Khan both owe their elevation to ‘Tansenhood’ to their extraordinary sway over Malkauns. To hear Bhimsen’s paga lagana de on a good day is to come away an ennobled being. Although the recording adduced here is very good, it scarcely does justice to Bhimsen’s powers.

Master Krishnarao

Amir Khan‘s recording, on the other hand, is manna for the soul. The vilambit composition, jinke mana Rama biraaje, places its sam on the mandra komal nishad. To hear him enter the final ti-ra-ki-Ta orbit leading up to the sam is to experience moksha here and now. I will never forget the kaleidoscopic display of expressions and emotions that would envelope my father’s visage every time this LP perched on our turntable. Three selections are offered, the last two still among the unpublished.

We close the Malkauns segment with Kishori’s prattle which, if nothing else, shows that there’s a funny bone in her.

There are many varieties (prakars) of Kauns. In most of these formulations, the template of raganga Kauns serves as the starting point. Occasionally, a Kauns prakar may not directly exhibit the swaric heritage of Malkauns but may instead be informed by its mannerisms.

Ragas Pancham Malkauns | Sampoorna Malkauns | Kaushi/Kaushiki

These ragas are brought under one umbrella because they share a common foundation. The related Kaushi Kanada also shares genetic material with these forms.

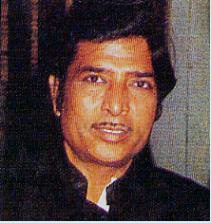

As the name suggests, Pancham Malkauns comes to be when pancham is dropped into Malkauns, usually in an avarohi prayoga such as g M d P or g M d n d M P. The arohi flow retains the Malkauns contours. Amir Khan shows how.

Amir Khan

A variation of Pancham Malkauns goes by the name Sundarkauns.

In Raga Sampoorna Malkauns, both R and P are added to the Malkauns template. Again, while the arohi behavior hews to the Malkauns line, rishab and pancham primarily participate in vakra avarohi phrases. This basic idea is also embraced in ragas Kaushiki and Kaushi although the precise handling of swaras may show variation.

Jha-sahab presents Raga Kaushi, in which strands of Bhimpalasi are seen: he Mahadeva.

Sampoorna Malkauns is a specialty of the Atrauli-Jaipur school. Mogubai Kurdikar is accompanied by her daughter Kishori in this lovely unpublished performance.

Their Atrauli-Jaipur confrere, Mallikarjun Mansur, shifts his sam to the pancham.

Nikhil Banerjee‘s performance in Raga Kaushiki from a Dover Lane conference in Kolkotta in the 1970s.

Mogubai Kurdikar

Raga Chandrakauns (Bageshree-anga)

This old, pentatonic version of Chandrakauns is composed of: S g M D n. The presence of D imbues it with Bageshree-like features to which is joined the Kauns anga. Since it is a type of Kauns, the emphasis is on highlighting the Kauns anga. This cast of Chandrakauns is infrequently seen, today displaced by the more popular (and more melodious) recension to be described in the next section.

S.N. Ratanjankar‘s composition is relayed by his disciple Dinkar Kaikini: vighana hara Ganesha.

Raga Chandrakauns (Malkauns-anga)

The neoteric Chandrakauns, introduced by the Gwalior musicians, is also of pentatonic build – S g M d N – and has established itself as the default version. A simple switch from n to N in the Malkauns axis yields the swara-set for this Chandrakauns.

The general lakshanas stay true to Malkauns but a few subtle changes wrought by N call for attention. For instance, the nyasa on mandra nishad via M g S N. Other subtleties – sookshma-bheda – between Malkauns and Chandrakauns will reveal themselves to the experienced musician. Some few employ rishab occasionally as a sparsh-swara (brief touch) especially in the tar saptaka.

Lata Mangeshkar and Ravi Shankar in 1960 and 2002

SAMPOORNA RAMAYANA (1961), Lata Mangeshkar‘s voice, Vasant Desai‘s composition: san sanana.

A nom-tom alap by the senior Dagar brothers, N. Aminuddin and N. Moinuddin. At the tail end (2:28) notice the sparsh of the shuddha rishab.

The sisters – and daughters of Abdul Karim Khan – Hirabai Barodekar and Saraswati Rane.

Hirabai Barodekar (l) and Saraswati Rane (r)

Lakshmi Shankar: kavana bana aayi.

An unpublished tarana by Amir Khan.

Sharafat Hussain Khan of Atrauli-Agra.

Sharafat Hussain Khan

Raga Chandrakauns (Agra style)

This maverick strain is adopted by one branch of the Agra family. With both n and P included, it resembles the Sampoorna Malkauns relished by the Atrauli-Jaipur musicians. A distinguishing artifact is the avarohi the use of komal rishab.

Latafat Hussain Khan begins with a composition of “Daraspiya” (Mehboob Khan of Atrauli): begi awana kara.

Interestingly, another offshoot of Agra sings a similar formulation but with a shuddha rishab. Earlier, we had Sharafat Hussain singing the modern Chandrakauns in standard format – and he was a pupil of Vilayat Hussain Khan “Pranpiya,” one of the pillars of Agra. Really, these Agra punters are inscrutable.

Raga Kaishiki Ranjani

This raga which takes after the modern Chandrakauns was incubated in the mind of Chidanand Nagarkar (1919-1971), a pupil of Acharya S.N. Ratanjankar. The key idea here is the bold introduction of shuddha rishab in vakra phrases.

S.N. Ratanjankar

The following tonal progression captures its essence:

S, d’ N’ S R, g R g M

g M d N, d N S”, d N S” R”, g” R” S” N

d N S” R” S” N d, N d M, g R g M, g M (g)R S

Kaishiki Ranjani has caught on with the vocalists. C.R. Vyas has composed a couple of attractive bandishes; Jitendra Abhisheki, Prabhakar Karekar and others have made it a fixture in their repertoire.

Nagarkar had a winsome style but alas, a stroke of misfortune snatched him away before his time. He was also a gifted composer with ‘Chit-Anand’ as his mudra. Here he sings his own definitive Kaishiki Ranjani compositions. To wit, the vilambit, eri ma’i piya, and the scintillating druta cheez, barkha rtu bairana.

Malini Rajurkar retails the same compositions.

Chidanand Nagarkar in a mehfil with Allah Rakha on tabla,

P. Madhukar on harmonium, and Ram Narayan on sarangi

Raga Madhukauns

A graha-bheda on the madhyam of the modern Chandrakauns yields the five swaras of this raga: S g m P n. The reader is by now surely au courant with the manoeuvres necessary to advance the Kauns anga.

The finest Madhukauns there is: Vasantrao Deshpande.

Vasantrao Deshpande

Very occasionally, we come across minor variations of Madhukauns, for instance, the introduction of dhaivat in the avarohi flow.

Raga Harikauns

This is yet another audav-jati prakar of Kauns with the swara-set: S g m D n.

Raga Devkauns

The final item in the Kauns roster, again audav-jati: S g M P N.

Aslam Hussain Khan of Khurja.

Acknowledgements

It is my pleasure to thank Romesh Aeri, Ashok Ambardar, V.N. Muthukumar, Ajay Nerurkar and Sir Vish Krishnan. Anita Thakur, let it be said again, is the reason this series of articles came to be.