by Rajan P. Parrikar

First published on SAWF on September 3, 2001

Rajan P. Parrikar

Namashkar.

In the comity of ragas, there is a certain class of denizens ordained to be “kshudra prakriti ke raga” by the long arm of tradition. They are so called because of their provenance in the folk idiom. A number of kshudra ragas are acknowledged as the mother lode of the highly structured, expansive ragas that nest at the top of the pecking order. The heavyweights are the preferred choice for formal classical treatment and they exercise their noblesse oblige by marshaling the dhrupads and the khayals devoted to them. The kshudra ragas, on the other hand, are mired in the native soil, and in sync with the pulse of the laity. They seduce us through the many subsidiary forms such as thumri, tappa, dadra, bhajan, geet and so on. In general, they do not figure in elaborate khayal or dhrupad settings and it is in this sense only that they are deemed “kshudra” (lit. small).

Our present subject Raga Khamaj is the cock of the walk of the kshudra block. Continuing with our exploration of the Hindustani ragaspace we now enter the inviting confines of the Khamaj orchard where a special son et lumière arranged by the the refined and cultured ladies of SAWF awaits us. The lark includes an added attraction – From the Carnatic Gallery, a compendium of enchanting perspectives from the South authored by V.N. Muthukumar, Ram Naidu and M.V. Ramana.

Throughout the discussion, M = shuddha madhyam and m = teevra madhyam.

Raga Khamaj

Khamaj represents three separate entities: that, raganga and raga. The Khamaj that is congruent with the 28th Carnatic melakarta, Harikambhoji, with the following scale set: S R G M P D n. The sampoorna-jati Raga Khamaj draws on all the notes from the parent that plus an additional shuddha nishad. The raganga kernel is encapsulated in the following tonal clusters:

G M P D n D, M P D-M-G

S” n D P D-M-G

In the Indian musical traditions, the swaras cannot be viewed as isolated tonal units. The Indian term “swara” should not be confused with “note” (in the sense commonly used in the West) or a tone with a specific assigned frequency point. The idea of swara circumscribes the ‘space’ around a nominal note as well as its interaction with itself and its neighbours mediated through kans, andolans and gamakas. This is the primary reason the essence of Indian music and the nuance of swara cannot be effectively conveyed through the written word or notation. It also explains why non-Indians (Westerners in particular) find themselves at sea upon first encountering Indian music.

The curvature and intonation of Khamaj’s locus classicus, D-M-G, are vital. This arc is found in other allied ragas but only in Khamaj is its uccharana fully realized. The tonal strips of the raganga outlined above direct the raga’s conduct. The rishab is varjit in arohi sangatis. The shuddha nishad, typically employed in upward movements, is on the whole subordinate to the komal nishad. The gandhar in the poorvanga and dhaivat in the uttaranga are the dominant swaras.

Let us explore the raga some more.

S, G M P D n D, [S”] n D, M P D-M-G

This tonal sentence elucidates the raganga. [S”] denotes a khaTkA on the tAra shaDaj. That is, a quick twirl of the type R”S”NS” or S”R”NS”.

G M P D N S”

G M P D n D, P D N S”

G M n D, P D N S”

G M D N S”

G M P N S”

Each of these tonal groups is a candidate for an uttaranga launch.

S, G M P D N [S”] n D, G M P DG M G, R S

Notice the langhan of the rishab in arohi runs, the deergha bahutva role assigned to D, as well as the D-G coupling, often put to good effect.

The Khamaj terrain ranges over all manner of melodic twists and turns and has been extensively mined. The kshudra prakriti ragas are permitted lattitude for play with vivadi swaras and the main raga thus elaborated upon usually goes by the prefix “Mishra.” The teevra madhyam is a prime vivadi candidate in Khamaj, used to ornament the pancham. There are also specialized constructs involving m that lead to interesting situations such as an avirbhava of Raga Gara – in this form, called Pancham-se-Gara – especially in renditions of thumri and dadra.

P m P M G, GMPDnD GMDNS”nD P m P M G

Raga Gara may be explicitly invoked through a graha bhedam (murchhana) by translating the original tonic to the pancham.

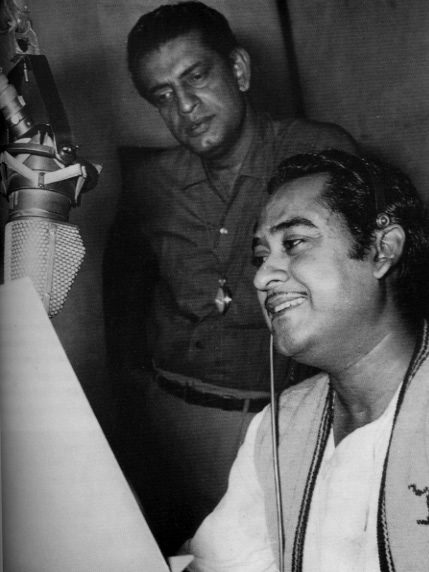

Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang” in concert

(© Rajan P. Parrikar)

It is scarcely practicable to list the myriad variations attending the Khamaj praxis. For a firm grasp, the raga has to do time in your mind.

Pandit Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang” kicks off with an inquiry into Khamaj structure. In the first clip, pinched off the telephone line, he discursively addresses the Khamaj domain, training his sights on its three principal members: Khamaj, Jhinjhoti and Khambavati. The discourse closes with a recitation of a famous dadra in Pancham-se-Gara to illustrate the insertion effect of the teevra madhyam indicated earlier. The reader is encouraged to be on the qui vive for the uccharana of the Khamaj arc D-M-G.

In this second cut, Jha-sahab responds to a query initiated by Raja Kale and Satyasheel Deshpande and clarifies the difference in intonation and curvature of the D-M-G uccharana in both Khamaj and Bilawal situations. The parley concludes with a dramatic recitation of Kabir’s words to drive home an important point about the nature of shruti and the premium placed on anubhava (there is no satisfactory English equivalent of this beautiful word) in Indian tradition.

The platter put together for this presentation features several inviting and rare delicacies. The amount of material available in Khamaj is forbiddingly large but our gauge limits admission to purveyors of the highest quality. Even the most exacting, fastidious palate ought to be sated by our selection. We begin with Lata Mangeshkar‘s rendition of Narsi Mehta‘s bhajan, a favourite of Mahatma Gandhi. The ennobling sentiments expressed and the tune dovetail beautifully: Vaishnava jana to.

Kishore Kumar rides a bong mule

Khamaj looms large in the folk music of Bengal. We adduce a composition of Rabindranath Tagore rendered by Pandit Kishore Kumar, Khalifa of the Khandwa gharana. Rabby was an extraordinary individual, a man possessed of transcendent intellect. While his appreciation of music was deep his musical talents were rather pedestrian if Robindra Shongeet is anything to go by. At its best his is “pretty” music. On the other hand, Pt. Kishore Kumar’s genius lay in music and music alone, to be sure, in the flourish of his vocal brush. Although Panditji came from Khandwa the bongs shamelessly claim him as one of their own. Even a cursory analysis of the eigenvalues of Panditji’s personality matrix betrays not a sliver of bong influence or trait. Panditji loved amangshor jhol, true, but the story goes that the day he discovered the pleasures of Goan prawn curry he foreswore the sissy bong cuisine for good. Every bong should put that in a pipe and smoke it.

Kishore Kumar‘s voice, Rabby’s bongspeak: bidhir bandhon.

K.L. Saigal‘s number from BHANWARA (1944) for master tunesmith Khemchand Prakash offers Khamaj vistas here and there: hum apna unhe bana na sake.

Shubha Mudgal adapts an old thumri tune to a modern orchestral arrangement in her rustic, full-throated babul jiya mora ghabaraye.

Hindi film numbers in Khamaj are legion but this one is a personal favourite. R.D. Burman is said to have received counsel from his illustrious father S.D. Burman while developing this tune. Lata brings a keen maternal instinct and love to flower in this flawless take. From AMAR PREM (1971): bada natkhat hai re.

From the Marathi stage comes this crisp composition of Govindrao Tembe for the drama MANAPAMAN, reprised in recent times by Prabhakar Karekar: ya nava navala nayanotsava.

Alladiya Khan, Govindrao Tembe

Next in line, a triple header from the fecund mind of Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang.” The first, a thumri in vilambit Keharwa, is seasoned with all the essential ingredients of Khamaj: na lage jiyara.

Another poorab-anga thumri, this time of a different design, in madhya-laya Teentala: jina chhuvo mori baiyyan.

The final item in Ramrang‘s suite: a bandish-ki-thumri, in Ektala: bole amava ki darana.

These were Jha-sahab’s own compositions. He imbibed the thumri technique from his guru, Bholanath Bhatt, who was regarded in his own day as one of the great masters of that form.

The well-known traditional bandish-ki-thumri – na manoongi – has many votaries but it is given only to ‘Aftab-e-Mousiqui’ Faiyyaz Khan to take it to the nines.

Vilambit khayal compositions in Khamaj are uncommon. More typical are sadra, dhamar, hori, dadra, thumris, khayalnuma and tarana.

Ulhas Kashalkar unwraps a traditional tarana (documented by Bhatkhande in his Kramik Pustaka Malika).

Kesarbai Kerkar

Kesarbai Kerkar‘s hori reveals her consummate command of voice, its modulations and phirat. A vivadi komal gandhar is casually dropped at 1:47 into the clip: aaye Shyam mose khelana holi.

Among the most celebrated thumri exponents of our time, Begum Akhtar uncorks a flavoured Khamaj: na ja balama pardes.

This thumri by Lakshmi Shankar, set to Deepchandi, is from a 1995 private mehfil. On the harmonium is yours truly, tabla support is provided by Pranesh Khan. We join in the climactic moments of the recital: aba na bajavo Shyam.

Nikhil Banerjee‘s fingers sing Khamaj in this delectable piece.

The richly gifted Sureshbabu Mane (1902-1953) inherited his yen for thumri from his great father Abdul Karim Khan. Some of papa’s vocal mannerisms are replicated in the son, as witness this recording of piyatirchhi nazariya.

True to form, the lifelong maverick Ramkrishnabuwa Vaze deals Khamaj in a brisk Ektala composition: piya nahin aaye.

Begum Akhtar (left) and Shanti Hiranand

By several accounts Barkat Ali Khan was a superior thumri singer but had to content himself playing second fiddle to his redoubtable brother, Bade Ghulam Ali Khan. Here he presents dekhe bina bechaina.

The same thumri by Bade Ghulam Ali Khan.

We ring down the curtain on Khamaj with a delectable thumri rendition by Siddheswari Devi: tumse lagi preeta, sanwariya.

Raga Jhinjhoti

Jhinjhoti’s warm, incandescent personality has earned for itself a permanent slot in the hearts of Indians. Some vidwans regard it as the principal raga of the Khamaj that (see for instance, Pandit Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande‘s commentary in his epochal Hindustani Sangeet Paddhati volumes) since its swara-set is exactly aligned with the parent that. The reader is encouraged to review Jha-sahab’s very first clip above.

Siddheshwari Devi (left) and Savita Devi

The distillate of the raga is represented in the following tonal sentence:

D’ S R M G, R G S R n’ D’ P’ D’ S

Jhinjhoti is best expressed in the mandra and madhya saptak. Typical forays are initiated from the mandra P’ or D’. Jha-sahab‘s commentary has already touched upon the chalan and associations with allied Ragas Khamaj and Khambavati. Here we shall content ourselves by depositing a few key phrases.

P’ D’ S R G M G, M G R G S, R n’ D’

This inchoative arohi movement is typical. The gandhar assumed a nyasa bahutva role but only in the avarohi direction.

S R M P D n D, P D-M-G, R G S R n’ D’ S

The gandhar is skipped (langhan alpatva) in arohi movement. The sentence is pregnant with the Khamaj raganga morceau D-M-G, although its intonation differs just a shade from that plied in Raga Khamaj.

R M P D n D, P D S”, S” R” n D P, D P M G, M G R G S

A sample uttaranga-bound foray. The andolan of n is a point of note.

It should now be obvious to even women and children that Jhinjhoti’s vakra build demands special tonal construction and careful handling of swara uccharana. In the hands of a master the raga exudes a magical aroma.

We begin with the soothing strains of dohas from Tulsidas‘s Ramcharitamanas, in Lata Mangeshkar‘s voice.

The Jhinjhoti exemplar from the Hindi film genre – Kishore Kumar borrows a tune from an earlier era for JHUMROO (1961) and casts it into a wistful jaunt down memory lane: ko’i humdum na raha.

Kishore Kumar, and behind him Satyajit Ray

Ramrang‘s exquisite composition is hobbled by fractured sound quality. Nonetheless we have salvaged and pieced together the outline: tana mana dhana main to varun re.

A burst of nomtom alap precedes this dhamar by Agra’s Vilayat Hussain Khan “Pranpiya,” assisted by his son Younus Hussain Khan: hori khelata Nandlal.

Vilayat Hussain Khan and Faiyyaz Khan

The Maihar statement from its distinguished representative, Ravi Shankar.

Aftab-e-Mousiqui Faiyyaz Khan.

From the Rampur-Sahaswan desk, a tarana by Mushtaq Hussain Khan.

The piece de resistance: Abdul Karim Khan‘s supreme rendition, the abiding masterpiece that gives the rest the look of schoolboy howlers: piya bina nahin.

Raga Khambavati

This Khamaj affiliate draws on both Khamaj and Jhinjhoti for its genetic blueprint. A soupçon of Mand is thrown in for good measure and a special sanchari G M->S designed to be Khambavati’s signature rounds off the theme. The reader is once again urged to review Jha-sahab’s first clip.

Let us amplify on the highlights heuristically as Jha-sahab has done in his own Volume III of Abhinava Geetanjali.

Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang”

(© Rajan P. Parrikar)

S R M P, M P D n n D, n D P D S” R” n

This tonal sentence is redolent of Jhinjhoti.

S n D P D-M-G

This appeals to the Khamaj raganga.

S” D n P D M P G M->S

A strand of Mand is terminated with Khambavati’s signature. The molecule G M->S contains a soft meend from M to S. With N in lieu of n the tonal construct above yields an avirbhava of Mand (with appropriate insertion of R), a point recorded by Pandit Bhatkhande and also remarked upon by Jha-sahab. Occasionally the shuddha nishad is observed in uttaranga movements en route to the tar saptaka shadaj: M P N, N S”.

We open with D.V. Paluskar‘s classic recording of the “Daraspiya” (Mehboob Khan) composition, aali ri main jagi. The colophon can be heard in the antara. Keep your ears tuned for the G M->S signature.

Another traditional favourite, sakhi mukha chandra in Jhaptala, developed beautifully by Basavraj Rajguru.

Vazebuwa‘s take on the same composition. Notice the M P N foray in the uttaranga at 0:27.

Ramzan Khan of the Delhi gharana sings a composition of Mamman Khan, a leading figure of that school. Mamman Khan (d. 1940) was an expert vocalist and sarangi player and had for his students such notables as aarangi-nawaz Bundu Khan.

Mamman Khan

Narayanrao Vyas presents a composition of his brother Shankarrao: chalo ri aaja.

The Atrauli-Jaipur vocalists render a private version of Khambavati. Here the pancham is varjit and the swara contour is: S G M D n. The signature G M->S is retained and helps ward off Rageshree. The rishab is occasionally touched in the tar saptak. All these points are summarized by Ashwini Bhide. Note that Daraspiya’s composition is now co-opted to this version.

Finally, another variation offered by the eminent Atrauli-Agra ustad, Azmat Hussain Khan. The reader is invited to take his own measure.

Raga Tilang

This exceedingly sweet (“karnapriya“) raga is attained to by eliminating R and D from Raga Khamaj. The surviving audav contour assumes the following form:

S G M P N S”::S” n P M G S

But a mere scale does not a raga make. Tilang’s highlights are summarized below:

G M P n P M G, S

G M P N S” n P G M G

Notice how the avarohi movement drops M and embraces P-G in the second instance. A momentary hint of Bihag through G M P N is eradicated by subsequent construction.

G M P n P N S”, P N S” G” S” N S”R”NS” n P G M G

The rishab is verboten in textbook Tilang but it is common practice to deploy it in the tara saptak.

Like most of the ragas in this feature, Tilang springs from the folk music of the land. A Rajasthani wedding song of the Manganiars carries the germ.

S.D. Burman‘s keen appreciation for this raga is established in the next two numbers. Perhaps nobody else exploited Kishore Kumar‘s depth and range to the degree Burmanda did. S.D. Burman came from Tripura (not Bongland, mind you) and is rightly considered one of the most creative musical minds of our time. First, the song from YEH GULISTAN HUMARA (1972). The mise-en-scène has Dev Anand drooling around a succulent, luscious Sharmila Tagore (a bong, alas): gori gori ga’on ki gori re.

From SHARMILEE (1971), Kishore‘s sardonic kaise kahen hum.

Omkarnath Thakur, deft and delicate: nanadiya kaise neera bharo.

Once again, the irrepressible Vazebuwa.

Laxmibai Jadhav, a contemporary of Kesarbai and an affiliate of the Baroda Darbar, was trained primarily by Atrauli-Jaipur’s Haider Khan (brother of Alladiya Khan). Her thumri in Mishra Tilang is interesting for its liberal use of the dhaivat. Also notice the beautiful chhaya of Raga Nand introduced around 0:15 into the clip: deejyo mori navranga chunari.

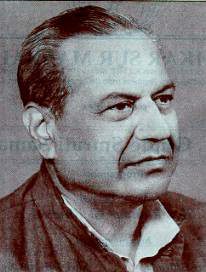

Sureshbabu Mane

Sureshbabu Mane: dekho jiya bechaina.

We wrap up the Tilang round with Abdul Karim Khan. Watch out for the caress of the tar saptaka komal gandhar at 3:27 into the clip.

Most of the remaining Khamaj derivatives addressed below have a somewhat localized compass, their performance limited to specific gharanas or performers. We will make short work of these melodies, touching upon their pertinent features.

Raga Kambhoji

In recent times this raga has come under the exclusive dominion of the Dagar clan. It has a strong resemblance to Jhinjhoti but a difference in formulation (chalan bheda) keeps the two apart. The madhyam is skipped in arohi sangatis thus provoking a chhaya of Kalavati. The andolita n and Jhinjhoti prayogas cut a familiar story.

G P D, P D, D P M G, R M G

G P P D D n D, n D S”, P D S” R n, D, P

The senior Dagar brothers, N. Aminuddin and N. Moinuddin, turn in a splendid performance.

(L-R): N. Moinuddin and N. Aminuddin Dagar

Raga Khokar

This is primarily an Atrauli-Jaipur specialty although its altered states are found elsewhere (vide Vazebuwa‘s Sangeet Kala Prakash). Govindrao Tembe suggests that Khokar may be viewed as a variant of Bihagda (vide Kalpana Sangeet). Bihagda itself is fashioned from an interplay of Khamaj and Bihag. The attack on the komal nishad here is pronounced and suggestive of Shukla Bilawal (also a Khamaj-infected prakar of Bilawal).

The ineffable splendour of Kesarbai Kerkar‘s performance is overwhelming. One instinctively senses a higher musical force at work here. The conception, execution and resolution of her tans as they take flight, soar and eventually swoop back into the orbit of the tala make for a awe-inspiring spectacle. Kesarbai’s artistry blew the curve, instituting for us a new touchstone for what defines the ne plus ultra. This bandish set in Jhaptala locates its sam on the dhaivat: mukha chandra.

On the heels of Kesarbai, Mallikarjun Mansur holds his own with the same bandish. It is a tough act to follow but Mansur’s display is nothing to sneeze at.

Raga Champak

To the casual ear this uncommon raga will sound no different than Khambavati. However, the latter’s key G M->S marker is absent in Champak. Another point of difference is the relatively higher importance accorded the madhyam.

Narayanrao Vyas alternates his ascent between G M P D S” and G M P D N. The komal nishad enters via the avarohi S” R” n cluster. The keen reader is encouraged to ferret out additional points of departure from Khambavati: bana mein bajavata bansi.

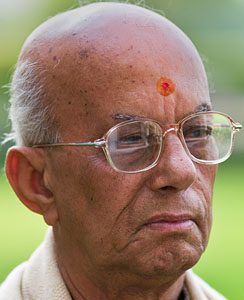

Omkarnath Thakur

Omkarnath Thakur‘s version takes a different turn. There is no shuddha nishad and the development devolves into hairsplitting with Khambavati. The cheez is set to fast-ish Jhoomra: maga jai ho.

Raga Deepak

This raga figures prominently in the mythos surrounding Tansen. Three types of Deepak have been traditionally acknowledged, subject to their that – Bilawal, Poorvi and Khamaj – affiliation.

The melodic activity of the Khamaj-that Deepak spans the mandra and madhya saptakas for the most part. The key phrases are:

S, R n’, D’ P’, P’D’ P’D’ M’, P’ N’, N’ S

SR SR (S)N, S M G, R S

S, GMPD, M, P n D, P, PD PD M, P G R S

K.G. Ginde presents a vilambit composition of his guru, S.N. Ratanjankar: chaunka puravo.

K.G. Ginde

Raga (Khamaji) Bhatiyar

Khamaji Bhatiyar bears no kinship to the very popular Bhatiyar of the Marwa that. In this type, there are chhayas of Khambavati, Jhinjhoti and Sindhura. The andolita komal gandhar is clearly discerned in this recording of Bande Hussain Khan, a member of the same extended family as Faiyyaz Hussain and Ata Hussain: Mahadeva Shiva Shankara.

Raga Gavati

Although the swaras of this raga nominally line up with the Khamaj that, they do not carry the burden of the Khamaj raganga. The following chalan captures Gavati’s essence:

G M P (S”)n S” (P)D, P, D M P G M R n’ S

S M, M P G M P n, S”, P n S” (P)D, P

Gavati is also known as Bheem. Some distinguish the two by adding to the latter a vivadi komal gandhar in the tar saptaka. Note that this Bheem is not the same as that of the Kafi that. For further discussion on Bheem/Gavati the reader is referred to Ramrang‘s Volume 2 of Abhinava Geetanjali.

Bade Ghulam Ali Khan is said to have taught Gavati to the great Carnatic vocalist G.N. Balasubramaniam who reciprocated by teaching Raga Andolika to BGAK. The druta bandish in this BGAK recording (para na payo) is cited in Ramrang’s essay. Bade Ghulam Ali Khan‘s unpublished Raga Gavati.

This 1960s recording of Nazakat Ali and Salamat Ali Khan is a modern classic.

Bade Ghulam Ali Khan

We conclude with Jitendra Abhisheki‘s performance where he sings two compositions of Ramrang, the vilambit khayal, aasa lagi tumhare charana ki and the druta cheez, humari para karo Sai.

This brings us to the end of our excursion. We have addressed almost all of its important members of the Khamaj family. Khamaj-that ragas such as Des ply their own raganga and thus merit a separate feature which we hope to bring to you in the fullness of time.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to my accomplices Romesh Aeri, Ashok Ambardar, Ajit Akolkar, Ajay Nerurkar and Guri Singh. But for Anita Thakur this series of articles would not have been. The project was her brainchild to begin with, and she continues to sustain it.

For perspectives on Khamaj-related ragas from the Carnatic tradition, see From the Carnatic Gallery.