by Rajan P. Parrikar

First published on SAWF on January 14, 2002

Part 1 | Part 2

Rajan P. Parrikar (Colorado Springs, 1991)

Namashkar.

In this conspectus, we delve into one of the great melodic pillars of the Hindustani tradition: Raganga Raga Kalyan, known variously as Yaman, Iman, Eman, and Aiman. Though steeped in antiquity, Kalyan’s historical antecedents remain cloaked in obscurity, fostering mythologies, including the oft-repeated ipse dixit attributing its genesis to Amir Khusro. Here, we shift the focus to the Kalyan raganga, tracing its contemporary structure and performance nuances.

Raganga Kalyan and Raga Kalyan

Raga Kalyan, often used interchangeably with Yaman, shares its scale with Kalyani, the 65th melakarta raga in Carnatic music. For a comprehensive Carnatic perspective, the reader is directed to the companion feature Kalyani by Dr. V.N. Muthukumar and Dr. M.V. Ramana. Within the Hindustani tradition, Kalyan can signify a that, a raganga, or a standalone raga.

Throughout this discussion, M = shuddha madhyam and m = teevra madhyam.

The term raganga, derived from the conjunction (sandhi) of “raga” and “anga,” refers to a compendium of tonal phrases and supporting uccharana abstracted from a ‘parent’ raga. Typically drawn from the pool of foundational ragas, the raganga serves as a melodic blueprint or “DNA” for the family of ragas it governs. It embodies the aesthetic grammar and gestural essence of its lineage. Viewed alternatively, it is a melodic generalization, analogous to a scientific law applied to specific instances. In this framework, the “parent” or “raganga raga” best exemplifies these principles and supplies the formative material for the raganga. For example, Raga Bhairav anchors the Bhairav raganga.

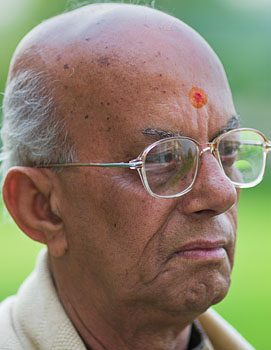

Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande

Kalyan’s place among the ten foundational thats was cemented by Pandit Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande, the eminent scholar and architect of modern Hindustani musicology. It is characterized by the following swara set: S R G m P D N. Raga Kalyan employs all seven swaras and is therefore classified as a sampoorna jati raga. Central to its identity are the raganga-vachaka swaras — the definitive tonal clusters that form its melodic signature.

1) S, N’ D’ N’ R G R S

In this poorvanga cluster the mere hint of N’ R G R S at once suggests the onset of Kalyan. Notice the characteristic langhan (skipped) shadaj in the arohi movement.

2) G m P->(mG)R, S

A seminal tonal sentence; the uccharana (intonation) of the P–>R coupling, mediated by a grace of the teevra madhyam and gandhar, represents a key raganga gesture. The P–>R coupling is also observed in Ragas Gaud Sarang and Chhaya but in each of these instances it is kept distinct by their respective uccharana. Recall the dictum: uccharana bheda se raga bheda. It is this manner of subtlety and sophistication of the idea of swara that elevates Indian music to a level unmatched and unattained by any other civilization.

Let us digest this assertion with a brilliant demonstration of the varied modes of P–>R coupling by Pandit Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang.”

3) m D N D P

This tonal strip furnishes a bridge to poorvanga and uttaranga tonal traffic.

4) S” N D N D P

This avarohatmaka phrase in the uttaranga completes the raganga abstract.

Raganga Kalyan is verily the mother lode of several ‘big’ ragas, its fecund terrain allowing for melodies to flow naturally from variations imposed on its kernel. A sufficiently insightful musician should to be able to ‘see’ the resulting linkages. For instance, the chalan of Ragas Bhoop and Shuddha Kalyan may be inferred from the raganga. It is important to note that the historical development may not have followed this sequence and that a raga may predate its raganga. Nevertheless the raganga viewpoint provides a powerful unifying framework attending the thought processes that have counseled the Indian musical mind through the ages.

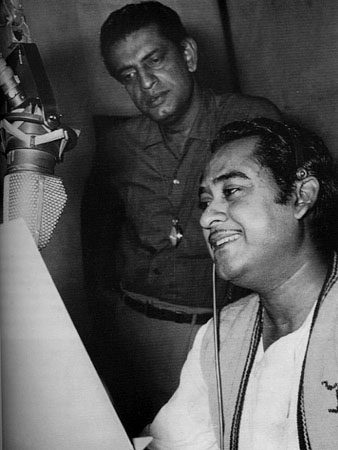

Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang” at the author’s home in Goa (2000)

Some additional details of the flagship of the Kalyan raganga – Raga Yaman – bear scrutiny. The existence of several nyasa sthanas – S, R, G, P, N – is indicative of its expansive melodic space. The teevra madhyam is often elongated during the elaboration portion of the performance. The odd one out is dhaivat – we make short shrift of it since a nyasa there is damaging to the raga dharma. Some of the launch phrases for the antara are now outlined:

G m D S”

m D N S”

P P S”

P (m)G P P N D S”

The skipping of shadaj and pancham in arohi movements – N’ R G and m D N – lends Yaman a distinct locus. Some musicians (typically non-Indians) tend to view these two tonal molecules as symmetric on account of their prima facie intervallic likeness. Viewing the raga structure in terms of intervals is a seriously flawed enterprise and completely misses its essence. No Indian musician worth his salt thinks in terms of intervals, not as a matter of instinct anyway. Apropos of the above two apparently symmetrical tonal molecules, the vital point is that R is a nyasa bahutva swara in both the arohi and avarohi directions whereas D enjoys no such treatment.

The langhan alpatva of S and P is sometimes observed in avarohi movements as well. To wit, R” N D m G R. Although the skipping of S and P is part of Yaman’s normative behavior, the inclusion of arohi S and P is not verboten. A deliberate construct such as S R G m or m P D N is observed in bandishes and tans (as some of the clips will later attest). Other features seen in performance – leaps spanning G-N and N-G, m-N and N-m.

Putting back together the pieces, a sample chalan is formulated:

S, (N’)D’ N’ R G(nyasa), R S, G m D N(nyasa),

S” N D N D P(nyasa), m (G)R G(nyasa), G m P->(mG)R(nyasa), G R S

This completes the introduction to the lakshanas of Raga Yaman. It is not possible to chronicle every auxiliary gesture or construct deployed. A careful study of the clips is urged so that the key ideas are settled and assimilated. Kalyan is so pervasive that there is little divergence in its behavior across gharana boundaries. The differences, when they are observed, are more of proportion of particular melodic gestures rather than of design.

Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang”

© Rajan P. Parrikar

The inclusion of shuddha madhyam M in Raga Yaman gives rise to the unfortunately-named Raga Yaman Kalyan (sometimes also called Jaimini Kalyan). This nomenclature is widespread but not universally accepted and one comes across the occasional musician partaking in the shuddha madhyam under the ‘Yaman’ brand itself.

The nature of M in Yaman is not unlike that of a vivadi swara; soft and judicious use occasions moments of great delight. Latitude is allowed in the frequency of occurrence and swara-lagav for these are matters of stylistic taste. Except for the shuddha madhyam-laden tonal construct in the poorvanga the rest of the structural contours of Yaman Kalyan are congruent with Yaman. The distinguishing phrase assumes the following form (or a minor variation of it):

N’ R G, m G R G, M G R S

The shuddha madhyam does not have an independent existence. It is either sandwiched between the gandhars – G, M G – or receives a kan of gandhar – (G)M G R S. In particular, a direct approach from the pancham can be ungainly (P M G – not!). Occasionally, and especially in the lighter genres, the chromatic slide m M is heard.

These ideas are encapsulated superbly by Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang” in this discussion pinched off the telephone line. Such is Jha-sahab’s sweep and precision that once he is done speaking on a raga virtually nothing more needs to be said on the subject.

As the preeminent night-time raga, Yaman embodies considerable gravitas. No other raga has cut so wide a swathe across all genres of music and no other raga has purchased so viselike a hold on the Indian’s thoughts and feelings. Every child embarking on a preliminary study of classical music brings with her a working familiarity of Kalyan obtained through folk and other sources. Yaman has come to be acknowledged as the touchstone among classical musicians in calibrating a peer’s quality and depth, its mastery deemed a sine qua non for any serious student. This magnitude and extent of Yaman’s reach impel us to offer here a substantial listening experience both in the realm of the ‘light’ and the classical.

In the posse of clips that follows, the Yaman and Yaman Kalyan items are commingled.

Yaman – The ‘Lighter’ Side

That Yaman has seduced every creative mind of the post-recording era generation is evident from the enormous volume of documented work. Here we must content ourselves with only a modest slice of that output. Not every ‘light’ composition will align with Yaman according to Hoyle, but some important, and sometimes surprising, gesture will be manifested in each of the adduced clips. This session should serve as a master class in the nexus between classical and ‘light’ music.

We open with an invocation to Ganesha, an arati in Marathi, written by the 17th century saint Swami Samarth Ramdas. Hridaynath Mangeshkar‘s tune and Lata‘s voice are joined in this hymn dearly loved in Goa and Maharashtra: sukha karta dukha harta.

Lata Mangeshkar

Lata again beseeches Ganapati: tujha magato mi aata.

Another prarthana to Ganesha. Vasantrao Deshpande is joined by Anuradha Paudwal: prathama tula vandito.

M.S. Subbulakshmi‘s ethereal voice infuses the chant, vande padmakaram.

Asha Bhonsle‘s in the Marathi movie MAHANANDA (1985). Composer Hridaynath Mangeshkar: maage ubha Mangesh.

Kalyan is Lata and Lata is Kalyan. Not even the classical masters can hope to hold a candle to the magic she conjures in this terrain.

These verses from the Bhagavad Geeta are set to music by Hridaynath.

Another bhakti rasa assay, this time from the Gurbani. The transcendent words of the 3rd Guru, Amardas, are set to music by the Singh brothers and rendered by Lata: mila mere preetama jiyo.

Tulsidas‘s feelings for Shri Rama are famously expressed in his Shri Ramanchandra krupalu bhajamana.

Meerabai‘s bhajan, Hridaynath‘s tune: kenu sanga.

From BHABHI KI CHOODIYAAN (1961), a luscious Yaman-based beauty set to music by Sudhir Phadke: lau lagati.

The next two corkers were conceived in the fertile mind of Madan Mohan. From BAHAANA (1960), ja re badara bairi ja.

Film: ANPADH (1962), jiya le gayo.

Roshan

Ghalib‘s exceptional ability with verse more than meets its match in Lata in this memorable composition set to music by Faiyaaz Shauqat: har eka baat pe.

Vasant Desai finds an ally in Lata‘s gentle treatment of swara. From ARDHAANGINI (1959), bade bhole ho.

Film: SHOKHIYAAN (1951), Music: Jamal Sen: supna bana sajana aaye.

Film: SUNHERE QADAM (1966), Music: Bulo C. Rani: maangne se.

Film: PAKEEZAH (1971), Music: Ghulam Mohammad: mausam hai.

Film: SATI SAVITRI (1964), Music: Laxmikant-Pyarelal: jeevana dor.

Ragas Yaman, Bhairavi and Pahadi have been mined extensively by the Hindi film composers. Roshan and Madan Mohan, in particular, had a very special relationship with Yaman. In their shared penchant for conceiving melodies that blended intimately with the lyric, in their drawing on India’s classical music and traditional bandishes, and in their attention to the design of the interludes, they seemed to be cut from the same cloth. Both remained in a state of creative ferment throughout their relatively short lives. Roshan‘s genius came to full flower in Yaman as witness the extraordinary compositions that follow.

Film: RAGRANG (1952), a take on the very popular classical bandish, eri aali piya bina. The words of the mukhda are attributed to Meerabai. Lata delivers admirably.

Govindrao Tembe

A haunting composition from MAMTA (1966), distinguished by Lata‘s intensity of feeling. Co-singer: Hemant Kumar.

In this immortal composition, with its celebrated sarod and flute interludes, Roshan draws inspiration from an old Yaman Kalyan composition, manaa tu kahe na dheera dharata aba, words of which are attributed to Tulsidas. Lyricist Sahir Ludhianvi‘s knock-off reflects Tulsi’s sentiment in the movie CHITRALEKHA (1964). Mohammad Rafi: mana re tu kahe na dheera dhare.

Roshan and Sahir combine again in the following three classics.

Mohammad Rafi in BARSAT KI RAAT (1960): zindagi bhar nahin.

Asha Bhonsle‘s tour de force in the qawwali from DIL HI TO HAI (1963): nigahen milane ko ji chahata hai.

Film: BABAR (1960), Voice: Sudha Malhotra: salam-e-hasrat.

We change tracks now.

Bhimsen Joshi is joined by Vasantrao Deshpande in this abhanga set to music by Ram Kadam: tala bole.

Bhimsen Joshi in yet another bout of bhakti, in this magnificent creation of the bel esprit Govindrao Tembe. Look out for the first occurrence of atmaranga rangale for the piercing streak in Bhimsen’s voice: mana ho Ramarangi rangale.

Two of Goa’s finest creative minds collaborate in the next enterprise: the poet laureate B.B. Borkar and the musician-composer par excellence Jitendra Abhisheki: kashi tuzha.

Bhimsen Joshi

Bhaskarbuwa Bakhale‘s enduring tune by Kumar Gandharva in a natyageeta from SWAYAMVAR: natha ha mazha.

This natyageeta from SAUBHADRA brings sweet childhood memories as I recall my father’s superb renditions in his role as Narada. Sharad Zambekar: Radhadhara madhu milinda.

Asha’s recital of Sant Dnyaneshwar‘s poetry, set to music by Hridaynath, is glorious enough to give one pause before conceding the Yaman dominion to Lata: kanada-o-Vitthalu.

K.L. Saigal‘s hit from ZINDAGI (1940), Music: Pankaj Mullick: main kya janu.

K.L. Saigal in TANSEN (1943), Music: Khemchand Prakash: diya jala’o.

The transparent sincerity in Mukesh‘s voice has deposited quite a few Yaman-based compositions permanently into the public memory bank. This bhajan composed by Lacchiram, for instance: chhoda jhamela jhoothe jaga ka.

Madan Mohan‘s gem from SANJOG (1961): bhooli hui yadon.

Who hasn’t heard of this jeremiad from PARVARISH (1958), tuned by Dattaram? aansoo bhari hain yeh jeevan ki rahein.

Rafi, Lata, and Mukesh

Every college Romeo has at some stage allowed himself the fantasy of wooing a babe with this well-worn number from SARASWATICHANDRA (1968), under Kalyanji-Anandji‘s baton: chandan sa badan.

Mukesh finds some more romance in this Sardar Malik classic from SARANGA (1960): saranga teri yaad mein.

We now turn to the suzerain from Khandwa, Pandit Kishore Kumar.

Panditji’s first offering is a canonical Khandwa cheez from ANURODH (1977) composed by Laxmikant- Pyarelal: aapke anurodh pe.

Panditji deals dhrupad-anga treatment to this sadra in Jhaptala, composed by the Punjabi ruffian O.P. Nayyar in EK BAAR MUSKURA DO (1972): savere ka sooraj.

Panditji coos wistfully for composer Hemant Kumar in KHAMOSHI (1969): woh sham kuch ajeeba thhi.

Panditji sings Anu Malik‘s tune in AAPAS KI BAAT (1982): tera chehra mujhe gulab lage.

The final gem from the Khandwa trove from CHALA MURARI HERO BANNE (1977) nicely illuminates the raganga lakshanas: na jaane din kaise.

Kishore Kumar and Satyajit Ray

Ghalib‘s classic ghazal is tuned by Ghulam Mohammad for Suraiyya in MIRZA GHALIB (1954): nuktacheen ha gham-e-dil.

Another ghazal of Ahmad Faraz delivered by the gifted Mehdi Hasan: ranjish hi sahi.

The Pakistani songstress Farida Khanoum‘s stentorian voice takes charge: woh mujhse.

Only rarely did Laxmikant-Pyarelal surpass themselves, one such instance being the movie PARASMANI (1963): woh jaba yaad aaye.

Ravindra Jain‘s handsome tune in CHITCHOR (1976) was a rage following its release. K.J. Yesudas: jaba deep jale.

Rafi and Kishore Kumar

Feminine beauty and form are extolled in this luscious composition of Shambhu Sen rendered by Mohammad Rafi in MRIG TRISHNA: nava kalpana nava roopa se.

We wind down this Ya’mania’ with a couple of Shankar-Jaikishan compositions. Their folksy number in TEESRI KASAM (1966) was in its day the national chant. A rollicking Asha rises to the occasion: paan khaye saiyyan.

In LAL PATTHAR (1971) we watch in despair as Manna Dey comes a cropper vis-a-vis Asha. It hurts to see an adult man whipped so badly by a girl but the pain is instantly diminished by the realization that the male in question is a Bong. Those Manna Dey tans are indistinguishable from the bawling of a freshly baked baby as it tries to cope with life outside the amnion: re mana sur mein ga.

The Yaman story continues in Part 2.

Part 1 | Part 2