by Rajan P. Parrikar

First published on SAWF on October 3, 2005

Rajan P. Parrikar (Colorado, 1991)

Namashkar.

The hoary Raga Bhinna Shadaj and its derivative melodies will absorb our interest in this installment.

Raga Bhinna Shadaj

This old raga finds mention in the treatises of antiquity, among them Matanga‘s Brhaddesi (9th C), Sarangdeva‘s Sangeeta Ratnakara (13th C). Resolving the conflicting accounts in the commentaries and relating the lakshanas of the ancien régime with the practice of our time present considerable difficulties. “Bhinna (lit. differentiated) is so called because it is differentiated with reference to four (factors) viz. sruti, jati, purity and tone (svara)” (Sangitaratnakara of Sarngdeva, Vol. II, English Translation and Text by R.K. Shringy and Prem Lata Sharma, Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd., 1989). Bhinna Shadaj seems to refer to that grama-raga obtained by deviating from the shadja-grama-raga (likewise with Bhinna Pancham and the madhyama-grama). Sarangdeva is explicit in his description of Bhinna Shadaj: “Born of sadjodicyav (jati), bhinnasadja is devoid of rsabha and panchama, has dhaivata as its fundamental and initial note and madhyama for its final note?” (Ibid). This is seen to correspond to the present-day version of the Hindustani Raga Bhinna Shadaj at least in its broad outline (the Carnatic raga of the same name is very different).

Throughout this screed, M represents the shuddha madhyam. The swaras of the mandra saptaka are denoted by ‘ and those of the tar saptaka by “. A swara encased in round parenthesis furnishes a grace to the swara immediately following it.

Subbarao, author of Raganidhi

Bhinna Shadaj is an audav-jati raga with the following swara profile: S G M D N. The rishab and pancham are varjit. It is known by several other names: Kaushikdhwani, Hindoli, Audav Bilawal, and Bhookosh/Bhavkosh/Bhavkauns. See Raga Vyakarana by Vimalakanta Roy Chaudhury (Vani Prakashan, 1998), and Raganidhi by B. Subba Rao (Music Academy, Madras).

The lakshanas are straightforward: it is an M-centric (madhyam-pradhana) raga, and allows for nyasa on each of its swaras. This happy situation permits a large space for elaboration as well as varied points of swara emphasis. The avarohi (downward) contour is characterized by the meends G–>S, D–>M and S”–>D.

Let us write down some representative tonal phrases:

S, D’ N’ S G M, M, G, G–>S

(N’)D’ N’ S G M, G M D G M, M, G

G M (N)D, D, D N, N S”, S”–>D, G M G–>S

GMDNS”, D N S” G” M” G”–>S”, S”–>D, N–>D->M, G M G–>S

These preliminaries are summarized by Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang.”

In his Sangeetanjali (Omkarnath Thakur Estate Trust, 1959), Omkarnath Thakur reflects on the raga’s “shanta-gambheer” bhava, the preponderance of its madhyam, and the role of other swaras. A substitution of shuddha madhyam with its teevra counterpart, he writes, brings forth Raga Hindol with its “teekha” and “ugra” (intense, fierce) bhava.

At the top of our audio buffet we have a course of ‘light’ melodies inspired by the Bhinna Shadaj motif. In this area, we seek not a strict fidelity to the raga structure, rather a melodic scaffold that is recognizably of Bhinna Shadaj extraction.

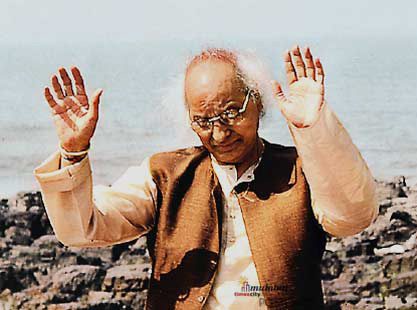

Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang” (Delhi, Feb 2007)

Meerabai’s song, composed by Hridaynath Mangeshkar, delivered by Lata: uda ja re kaga.

Bade Ghulam Ali Khan‘s wistful classic continues to move us deeply: yaada piya ki aaye.

Bade Ghulam Ali Khan and Lata Mangeshkar

In BAHURANI (1963), C. Ramchandra modeled his composition after the preceding BGAK thumri. Lata Mangeshkar: balama anari mana bhaye.

Movie: BAWARCHI (1972), Composer: Madan Mohan, Voice: Manna Dey. The asthai is of interest to us, the antara strays elsewhere: tuma bina jeevana kaisa jeevana.

From MAA BEHEN AUR BIWI (1973), the composer is Sharda, the singer Mohammad Rafi: achcha hi hu’a dil toota gaya.

In the classical round that follows, the reader is invited to take stock of the treatment accorded the raga as it journeys through diverse gharanas, hearts and minds.

We open with the finest Bhinna Shadaj there is. No man or woman, compos mentis, can escape the force of Kishori Amonkar‘s genius on display here. Notice the occasional rishab in the upper register.

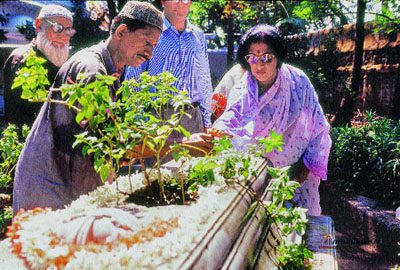

Kishori Amonkar at Alladiya Khan’s grave in Mumbai

Enter Banditji, the Mewati cockalorum. On his website we learn that in fruits he loves “apples, pears and papaya.” This is not to say that lemons and taut, succulent melons hold no charm for him. Whatever your fruit, Banditji-bhai can be counted on to make, er, a clean breast of it.

Banditji’s vilambit khayal is Sadarang‘s, the cheez seems to be a composition of Sugharpiya, colophon of the harmonium master, dhrupadiya, and thumri composer, Bhaiyya Ganpatrao (1852-1920).

As mentioned earlier, this raga is also known as Kaushikdhwani.

Exponent of the Kirana style, Mani Prasad.

Nazakat Ali Khan and Salamat Ali Khan.

Ram Narayan on sarangi.

Some musicians, notably of the Agra school, go with the “Hindoli” brand name.

Banditji surrenders

This concludes the Bhinna Shadaj segment. A recording of Amir Khan’s Hindoli exists, but could not be procured in time for this article. We next turn our attention to the variations on the Bhinna Shadaj theme where the same, basic idea runs through three ragas, namely, Hemant, Chakradhar and Sohani-Hindoli.

Raga Hemant

This raga was advanced by Baba Allauddin Khan of Maihar. Baba’s boy, the dark and dimunitive (naked) Emperor Alu, rules from his potty throne in San Rafael, California. During Alu’s reign, Google has prospered, Saddam was vanquished, and the universe continued to expand.

(L-R): Allauddin Khan, Rajabhaiya Poonchwale,

Wadilal Shivram, S.N. Ratanjankar

Baba Allauddin’s choice of the raga name is curious. “Hemant” (winter) is embedded in Sarangdeva’s shloka on Bhinna Shadaj: “Having Brahma for its presiding deity, it is sung on the occasions of universal festivity in the first quarter of the day in winter [Hemant] to express terror (bhayanaka) and disgust (bibhatsa)” (Shringy and Sharma, op. cit.).

The basic idea in Hemant is the positioning of pancham and rishab in the downward locus of Bhinna Shadaj. The swara-lagav of pancham is measured, and occasions great delight if done right.

S”–>D-P-M

G M D N D (M)P M

Pancham is given a glancing touch, often with a grace of M as in (M)P M. Although the pramana of P in the overall scheme remains alpa, musicians bring along their individual spin to its lagav, as will be observed even within the Maihar pool.

G M (G)R, S or G R S

Rishab is deployed only in the avarohi mode. In the first instance above, it may be rendered deergha.

Hemant is a madhyam-pradhana raga and a little thought shows that a murchhana on madhyam gives rise to an avirbhava (onset, appearance) of Raga MaruBihag.

Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang” dispenses his pearls of musical wisdom.

The mukhda of composer Anil Biswas‘s delicate creation in JALTI NISHANI (1955) leans towards Hemant. Lata Mangeshkar: rooth ke tum to chal diye.

Expectedly, the Maihar contingent turns in a strong showing here.

We first turn to Ravi Shankar, whose interpretation of the raga may be regarded as the closest to what Baba had in mind.

Ravi Shankar’s shagird, Shamim Ahmed.

Nikhil Banerjee and Ravi Shankar

Nikhil Banerjee, sitar.

The outstanding (but alas, underrated) Bahadur Khan on sarod.

Raga Hemant has increasingly found favour among the vocalists, a rare instance in our time of a successful crossover from the instrumental provenance. Its voyage to the ‘other’ side, adaptation to the new idiom, and the retention of its moola tatva (core values) merit some consideration. Among the influential composers to have spun khayals in Hemant are Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang,” Balwantrai Bhatt “Bhavrang”, Laxmanprasad Jaipurwale and Dinkar Kaikini. Younger musicians such as Ashwini Bhide have also been active on this front.

Jha-sahab is enormously fond of Hemant and it shows in the several khayals he has fashioned. He outlines his composition, kahan mana lago in vilambit Jhoomra, and his cheez, bairana bhayo in druta Ektala, in successive clips. These make for instructive listening because we later have Jitendra Abhisheki rendering both of them in an actual performance.

Ramashreya Jha and Purushottam Walawalkar (Goa, 2003)

Jitendra Abhisheki learnt the druta cheez directly from Ramrang and worked on the vilambit himself off Ramrang’s written notation.

Ramrang sketches yet another composition, beeta gaye ri, set in vilambit Roopak.

Veena Sahasrabuddhe, invincibly middle-class, gets the melodics of beeta gaye ri right but founders on its tala-baddha aspect. The second composition in Teentala was also composed by Ramrang, the final item in druta Ada Chautala is due to Balwantrai Bhatt. This is one long whine by Ms. Sahasrabuddhe.

Dinkar Kaikini‘s manner of voice production always gives the impression that his nuts have come under severe duress in the middle of a root canal procedure. Other than that he is a fine singer.

Raga Chakradhar

The idea of soliciting pancham and rishab in avarohi prayogas within the Bhinna Shadaj framework didn’t begin with Allauddin Khan. In his work Kalpana Sangeet, Govindrao Tembe mentions a “rare” raga by the name Sunavanti, and based on the one cheez he knew, spells out its chalan. No more details are offered. The basic idea and structure appear similar to that of Hemant although the swarocchara cannot be conclusively inferred from the written word alone.

Balabhau Umdekar

Balabhau Umdekar, Darbar Gayak at Gwalior, introduced Raga Chakradhar into Hindustani music and detailed it in his book, Raga Sumanmala, first published around 1936.

The pancham is rendered varjit in arohi chalan but rishab is alpa. That is, both S R G M D N and S G M D N are admitted.

Umdekar adduces verses from the old treatises of Ramamatya, Somanatha and Ahobala in support of its lakshanas and writes that the raga survives in the Carnatic system under a different name: Saraswati Manohari (the Dikshitar school version). Carnatic afficionados are referred to Ragas of the Sangita Saramrta, Ed. T.V. Subba Rao and S.R. Janakiraman (Music Academy, Madras) for a discussion of Saraswati Manohari.

Despite its proximity to Hemant, a few points relevant to Chakradhar merit attention: rishab is permitted in arohi prayogas; the lagav of pancham appears coarse, not finessed in the manner it is in Hemant. Finally, the melodic arrow in Chakradhar points upward in the arohi direction whereas Hemant reveals its soul to the avarohi observer.

Gangubai Hangal and Mallikarjun Mansur

The two compositions heard in the clips are found in Umdekar’s book. The “Manrang” colophon is embedded in the text of the vilambit khayal.

Malini Rajurkar, Raga Chakradhar.

We end these ruminations with a teaser from Khadim Hussain Khan of the Agra school. The raga is called Sohani-Hindoli; the Sohani points to Shuddha Sohani, a type with the S G M D N chalan.

So there we have it. Three ragas – Hemant, Chakradhar and Sohani-Hindoli – independently conceived and separated in time and space, converging to a common melodic corner. Perhaps the lesson here is that we are, after all, not that much smarter than one another.

Acknowledgements

Romesh Aeri and Ashok Ambardar.

Sir Vish Krishnan.

Dhananjay Naniwadekar, for the Mohammad Rafi clip.

Sanjeev Ramabhadran, for suggesting the Lata song from JALTI NISHANI.

Anita Thakur.