by Rajan P. Parrikar

First published on South Asian Women’s Forum (SAWF) on April 29, 2002

Part 1 | Part 2

Rajan Parrikar (Cape Canaveral, 1989)

Photo by: Dr. Anand Bariya

Namashkar.

Our odyssey through the vast ocean of ragas now draws near its terminus ad quem: Raga Bhairavi. This melody, long enshrined as the customary conclusion of a Hindustani mehfil, marks the final chapter of these chronicles. (Note: After a hiatus, I resumed writing with the later installments of Short Takes.)

Throughout this discussion, M = shuddha madhyam and m = teevra madhyam.

The name “Bhairavi” is derived from one of the eight forms of the Devi, born in the solemn and haunting atmosphere of the cremation grounds. So deeply cherished and widely disseminated is Raga Bhairavi that even the untutored Indian rasika carries its elemental essence imprinted in memory. Bhairavi also stands as one of the ten fundamental thats proposed by the musical luminary Pandit Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande. Its core swara-set aligns with the 8th Carnatic melakarta, Hanumatodi: S r g M P d n.

What sets Bhairavi apart from its lofty counterparts is its remarkable versatility. Unique among the ‘big’ ragas, it embraces all 12 swaras in its expressive repertoire, a hallmark of the Bhairavi praxis. The five additional vivadi swaras, although not part of the raga’s foundational framework, are woven in with impeccable discretion, preserving the integrity of the raga-dharma. When adorned with these extensions, the melody is often termed “Mishra Bhairavi.”

Dhrupad and dhamar compositions abound in Bhairavi, and khayal renditions frequently feature druta compositions. However, vilambit khayal presentations, though rare, have been envisioned by composers such as S.N. Ratanjankar. Beyond the confines of Classical music, Bhairavi’s melodic footprint spans virtually every Indian musical genre — bhajan, geet, ghazal, qawwali, natyasangeet, Rabindra sangeet, and more — making it indispensable to the broader cultural soundscape.

In the ensuing discussion, we will delve into the central themes of Bhairavi before surveying its normative variations. While not exhaustive, this overview sets the stage for further exploration. The accompanying audio buffet promises ample opportunity for the curious reader to savour the finer details.

The driving phrases of the poorvanga are:

S n’ S r g M [g] r S

The square brackets on gandhar signify a shake of that swara that is sui generis to Bhairavi. This cluster at once precipitates the essence of Bhairavi.

g M d P, d P M P (M)g, M (g)r S

The rishab and/or pancham are often skipped in arohi prayogas, viz., n’ S g M d P.

The uttaranga forays are launched via: g M d n S”.

This tonal phrase is Malkauns-like. An extension of the idea is: g M d n S”, d n S” r” n S” (n)d P.

Since Bhairavi is a sampoorna raga, linear (“sapat“) runs of the S r g M P d n S” kind are frequently admitted.

Stitching together these elemental strips, a chalan of the ‘shuddha‘ swaroopa of Bhairavi is formulated:

S n S g M d P, (M)g M P d M P (M)g, d’ n’ S r [g] r S

g M d n S”, S” r” n S” (n)d P, d P M P (M)g, S r g M, (g)r S

The typical modus operandi for each the five vivadi swaras is now outlined.

Shuddha rishab: arohi – S, d’ n’ S R [g] r S ; avarohi – P, d P M P (M)g R g, r S.

Invocation of the vivadi R is common in most Bhairavi renditions.

Shuddha dhaivat: g M P d P, D n d P

Teevra madhyam: P d M P (M)g, g M m g r S

Shuddha nishad: S, r N’ S, d’ n’ S r [g] r S r N’ S

Shuddha gandhar: S r g M, M G M, S r G r S

Notice that shuddha gandhar does not lend itself to as good a fit in the Bhairavi aesthetic.

The nyasa swaras are S, g and P; in addition, M and d are often sought for elongation. Care has to be observed in the treatment of d so as to keep Asavari anga at bay. As to the vadi, there is no prevailing consensus. Traditionally, M has been considered for the role but in recent times the accent has shifted to other swaras. For instance, Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang” argues in his classic work Abhinava Geetanjali that d and G are the vadi and samvadi, respectively. These differences in outlook notwithstanding, there is no mistaking the core of Bhairavi.

A variation known as Sindhu Bhairavi retains all the mannerisms of the parent but with rishab augmented to its shuddha shade. These days Sindhu Bhairavi is sung with both rishabs and both dhaivats. Other variants such as Jangla Bhairavi, Kasuri Bhairavi and such like also exist. These are relatively minor offshoots originating from the Bhairavi stem; I prefer to locate them all under the “Mishra Bhairavi” rubric.

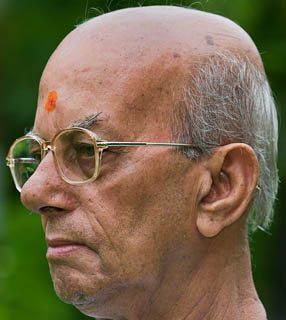

Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang”

© Rajan P. Parrikar

This completes our prolegomenon on Bhairavi’s structural matters. The raga affords a wide compass for rumination, and numerous melodic templates with which to develop its motif have evolved.

Obiter dictum: The profoundly significant Raga Bilaskhani Todi is carved out of swaras from the Bhairavi campus. The kinship ends there, for Bilaskhani Todi is a horse of an entirely different colour with its special prayogas, its Todi-anga uccharana and its meends. An inadvertent step into Bhairavi territory may deal the kiss of death to Bilaskhani.

In its width and penetration the work of Pandit Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang” is the only one in recent times that approaches the standards established by Pandit Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande (see Appendix at the end of this essay). Jha-sahab regards Bhatkhande as his param-guru, and has critically extended the Chaturpandit’s ideas on the nature and structure of raga. Jha-sahab’s raganubhava is an accretion of decades of reflection and play. To get there, the raga must have done time in your mind. Mere taleem won’t cut it. A musician with years of rigorous taleem and not much else is little more than a well-trained dog. This point cannot be underscored enough, for the Hindustani firmament is littered with the droppings of these “lakeer-ke-faqeer” chumps, these viveka-atrophied baboons.

Jha-sahab‘s parley opens with a demonstration of the vivadi swaras and then turns to the ragavachaka prayogas. There is also a discussion of Bilaskhani Todi vis-a-vis Bhairavi. This session (like many in this series of articles) was recorded over a California-to-Allahabad telephone link.

Bhairavi has been cultivated extravagantly by the Hindi film music composers. Many of the lasting creations of the 20th C have their roots in this raga. The distinction between ‘light’ and ‘classical’ is largely moot in this case since a good Bhairavi rendition is seen as “Bhairavi” without regard to genre or source. Indeed, as will be clear soon, the greatest Bhairavi on record sprung not under the auspices of the Classical world but through the artistry of a musical genius affiliated with the popular imagination.

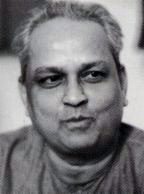

K.L. Saigal

The banquet we are about to sink our teeth into contains many inviting items, but bear in mind that it represents a tiny sample of the Bhairavi goodies extant. From this point on, I intend to practice severe economy of word and chime in only when, and if, necessary (if I can help it).

We begin with an invocation to that abiding symbol of learning, Goddess Saraswati. The text is a traditional description of the devi. The tune, credited to Allaudin Khan, was adapted by composer Jaidev for ALAAP (1977). Lata Mangeshkar is assisted by Dilraj Kaur: Mata Saraswati Sharada.

There has not been a greater exponent of Bhairavi than K. L. Saigal and this is not an opinion. It is in the fitness of things that we steal some moments with Saigal-sahab.

This number from MY SISTER (1944) was composed by Pankaj Mullick: aie katib-e-taqdeer.

Every Bhairavi that Saigal touched turned to gold. Soordas’s famous bhajan, for instance, from BHAKTA SOORDAS (1942), set to music by Gyan Dutt: Madhukar Shyam hamare chor.

With this song on your lips, your small-beer tale of a life can acquire the sheen of an epic at dinner parties. Composer Naushad pulls in an all-time pleaser for SHAHJEHAN (1946): jab dil hi toot gaya.

Lata Mangeshkar

These Saigal numbers reveal his mastery of Bhairavi and his flair for joining melody to word.

From KISMAT (1943), composer Anil Biswas, singer Amirbai Karnataki: ab tere siva.

A quick flavour of the creative ferment in Bhairavi can be had by examining Lata Mangeshkar‘s oeuvre.

From DULARI (1949), composer Naushad: aie dil tujhe.

It was fresh then and it is fresh now. The classic from GOONJ UTHI SHEHNAI (1959) composed by Vasant Desai: dil ka khilona.

Composer Madan Mohan, film DEKH KABEERA ROYA (1957): tu pyar kare.

Chitragupta‘s tune in MAIN CHUP RAHUNGI (1962): tumhi ho mata.

Ravi Shankar‘s classic from ANURADHA (1960): sanware sanware.

S.D. Burman in TERE MERE SAPNE (1971): jaise Radha ne.

Lata and Rafi

It is fashionable in the West to talk about the “complexity and beauty” of African drumming or the “intoxicating beauty” of Gammelan or this and that and the other. The ‘savage’ has now turned noble. Long before the advent of these childish Western fads, the brilliant Indian duo of Shankar-Jaikishan scoured the world’s musical hotbeds incorporating into their work the best from all lands while staying true to their Indian soul. For instance, their adaptation of this number of the celebrated Arab chanteuse, Umm Kulthum (1898-1975)…

…for the runaway superhit from AWARA (1951): ghar aaya mera pardesi.

Shankar-Jaikishan‘s fondness for Bhairavi and their unshakeable faith in Lata‘s artistry stood at the cradle of many of our national chants. These five corkers are all rooted in the soil of the land.

PATITA (1953), kisi ne apna bana ke.

(L-R): Anil Biswas, Lata, Pannalal Ghosh

MAYUR PANKH (1954), kushiyonke chand.

SEEMA (1955), suno chhoti si.

This number from BASANT BAHAR (1956) is also famous for Pannalal Ghosh‘s interludes on the bansuri: main piya teri.

DIL APNA AUR PREET PARAYI (1960), dil apna aur preet parayi.

Enter Mohammad Rafi.

From Naushad‘s workshop, this sparkling number was forged for MELA (1948): yeh zindagi ke mele.

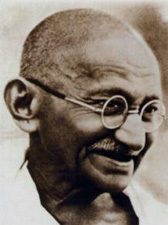

Mahatma Gandhi

Some years ago, a vast and shameless Bong conspiracy to wangle a brilliant Goan composer as one of their own was exposed. The man in question was N. Datta (Datta Naik), who teamed with Sahir Ludhianvi to give us many unforgettable numbers. From DHOOL KA PHOOL (1959), in Mohammad Rafi‘s voice: tu Hindu banega na Musalman banega.

(L-R): Jaikishan, Shankar, Lata, Talat

Mahatma Gandhi’s life is celebrated in song by the poet Rajinder Kishan, music composers Husanlal-Bhagatram, and Mohammad Rafi: suno suno aie duniyawalon Bapu ki yeh amar kahani.

Lata Mangeshkar and Mohammad Rafi in a soft Khayyam composition from SHOLA AUR SHABNAM (1961): jeet hi lenge.

Composer Roshan‘s turn. From DEVAR (1966), this is Mukesh‘s sole entry: aaya hain mujhe phir yaad.

Ladies, it is time to pull out your hankies. Talat-bhai, the quivering doyen of the ronaa-dhonaa brigade, is here. From DAGH (1952), composers Shankar-Jaikishan: aie mere dil kahin.

O.P. Nayyar goes balle balle, that unappetising Bhangra ritual invented by uncouth Punju primates. Asha Bhonsle and Shamshad Begum in NAYA DAUR (1957): reshmi salvar kurta.

Lata and Kishore Kumar

Pt. Kishore Kumar‘s garden has a few Bhairavi lilies blooming. Such as this riveting masterpiece from AMAR PREM (1971) fashioned by R.D. Burman: chingari ko’i bhadke.

S.D. Burman cajoles Panditji into nibbling at a few vivadi swaras in GAMBLER (1971): dil aaja shayar hain.

The great man once again in BEMISAL (1982) under R.D. Burman: kisi baat par main.

That completes our Hindi film-based round. We next turn to melodies in other languages.

Dnyaneshwar‘s transcendental words in this Pasayadan are set to music by Hridaynath Mangeshkar and recited by Lata.

Jyotsna Bhole

Marathi natyasangeet has liberally drawn on Bhairavi. The famous musician-actress of yesteryear, Jyotsna Bhole, in the drama KULAVADHU (1942), with music composed by Master Krishnarao: bola amrutabola.

Veer Savarkar

Jyotsnatai was born Durga Kelekar in a tiny village in Goa, younger sister of Girijabai Kelekar (Jitendra Abhisheki’s first guru). I am often asked about the suffixes “tai” and “bai” used on names of Maharashtrian and Goan women. Research has shown that they are tied to the woman’s biological cycle: “tai” is assumed at the crack of puberty and automatically turns to “bai” at the conclusion of menopause. As for women over 60 pretending to be the self-righteous virgins – we call them “Lata-didi.”

The Marathi drama SANYASTA KHADGA (1931) written by the Indian nationalist and freedom fighter Veer Savarkar features Dinanath Mangeshkar‘s arresting Bhairavi: sukatatachi jagi ya.

Kumar Gandharva

The Marathi musical EKACH PYALA (1919) is packed with memorable tunes. Kumar Gandharva: prabhuaji gamala.

Over to the Department of Kannada. Basavanna‘s vacana is tuned and rendered by Basavraj Rajguru: chakorange chandramana.

Rabindranath Tagore is represented through his famous mor beena delivered here by Debabrata Biswas.

We round off this section with a clip of Greek Rembetika music set in the scale of Bhairavi.

The Bhairavi story continues in Part 2.

Part 1 | Part 2