by Rajan P. Parrikar

First published on SAWF on May 29, 2000

Rajan P. Parrikar (Colorado, 1991)

Namashkar.

Our exploration of Hindustani ragaspace continues with a coup d’oeil of the hoary Raga Bhairav and members of its extended family.

Raga Bhairav

Bhairav connotes three entities: raga, raganga, and that. All the three converge only in the flagship Raga Bhairav. Concerning its etymology, “Bhairav” is an epithet of Lord Shiva, associated with his fierce, bhayanak swaroopa. In old treatises Bhairav is referred to as the adi-raga and comes attached with a wealth of lore. In his monumental exegesis Hindustani Sangeet Paddhati, Pandit Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande has sifted through Bhairav’s tortuous history and its passage through time in great, and sometimes painful, detail. We shall here confine ourselves to its contemporary musical structure and practice.

Bhairav is so fundamental to Indian tradition that its impaction on the nation’s musical soul can never be overstated. Even the unlettered in the land is familiar with its germ in some form or the other. The overlay of Bhairav strains on an quiet, bucolic Indian morning can be a purifying experience. Verily, it falls to the lot of the noblest of ragas, deserving of renewal and reflection every single day.

Throughout this promenade M = shuddha madhyam, m = teevra madhyam.

The swara set constituting the Bhairav that is: S r G M P d N. It is congruent with the 15th Carnatic melakarta Mayamalavagoula. The Bhairav raganga – referred to as Bhairavanga – is composed of two chief threads, one each in the poorvanga and uttaranga regions.

G M P G M (G)r, S

The point of note here is the special andolita komal rishab in the avarohatmaka movement. This uccharana is vital, represents Bhairav’s signature, and at once defines the raganga.

G M (N)d, d, P

This is the uttaranga marker of the raganga. The swara lagav of both r and d is andolita, a sine qua non for effective expression of the Bhairavanga.

The lakshanas of Raga Bhairav are now fleshed out:

G M (n)d, (n)d, P, P G M (G)r, S

The komal nishad, while nominally varjya, is nevertheless cultivated through an andolita dhaivat. That is to say, it is “gupt” (hidden), rarely set out explicitly in notation although in some of the old dhrupad compositions there is a somewhat less inhibited recourse to the komal nishad. Notice the pancham – ‘langhan alpatva‘ (skipped) in the arohi movement and ‘nyasa bahutva‘ (point of repose) in the avarohi movement. This is characteristic of ragadari music where a swara may be called upon to wear multiple hats in service of the raga. The swara, it must be emphasized, is not synonymous with note.

G M (N)d, (N)d N S”, N S” (N)d N d P

The dhaivat is caressed with a touch of shuddha nishad, the retreat from S”->d is mediated by a meend. The intonational nuance is difficult to convey through the written word but we now have at our disposal the fruits of modern technology – streaming audio at our fingertips. The subtleties of uccharana will be illuminated in the audio offerings to follow.

S G M P G M, G M (G)r, S r G M P

The rishab is often rendered alpa and skipped in arohi movements. An occasional deergha madhyam makes for a pleasing effect. The treatment of gandhar calls for careful handling since an inopportune nyasa may inadvertently invite Raga Kalingada (to be discussed later). Ragas Kalingda and Gouri of the Bhairav that use the same set of notes but embody different ragangas. See On Raga Lalita-Gouri.

Building on the foregoing discussion leads to the following sketch:

S, (G)r (G)r S, (N’)d’ N’ S, N’ S G M, G M (G)r, S

S r G M P, P G M (N)d, d, P, P GMPGM (G)r, r S

G M (N)d, d, P, G M P d N S”, r” S” N S” (N)d, d, P

The gayaki of the raga is complemented by linear arohi-avarohi runs (SrGMPdNS”:S”NdPMGrS) and other supporting gestures. With this propaedeutic we are now ready for a dip in the Bhairav ocean. The prefatory pieces are Bhairav-based samples drawn from the ‘light’ arena. The operative word here is “based. These ancillary genres often co-opt the scale of Bhairav but take liberty with its lakshanas.

We open with M.S. Subbulakshmi‘s bhajan from Jayadeva‘s Geeta Govinda: jaya jagadeesha.

M.S. Subbulakshmi

(From I&B Calendar 2005)

The Gemini composer duo of M.D. Parthasarthy and Emani Shankar Sastry brought forth this Lata number in SANSAR (1952): amma roti de.

Salil Chowdhary, by a long shot the most beautiful and complex musical mind to have come out of Bengal, files two beautiful Lata solos, one in MUSAFIR (1957): mana re Hari ke guna.

And the much loved melody from JAGTE RAHO (1956): jago Mohan pyare.

A haunting melody from composer Roshan in SANSKAR (1952), again in Lata‘s voice: hanse tim tim.

BAIJU BAWRA (1953) carried what is probably the most famous Bhairav-based composition in the popular imagination. Composer Naushad teams with Lata.

O.P. Nayyar throws caution to the winds in a cavalier romp through Bhairav territory. Asha Bhonsle figures in this PHIR WOHI DIL LAYA HOON (1962) sparkler: dekho bijlee dole.

On the Marathi stage the Bhairav scale is most strongly sensed in narrative musical passages known as ‘saki‘ (one may argue that Kalingada, not Bhairav, is the basis for these folk-inspired tunes). Vasantrao Deshpande flashes an instance of this sub-genre in the folksy (Lavani-esque) Hindi saki from SHAKUNTALA.

We switch off the ‘light’ round with a bhajan of the 14th C saint Namdev, rendered by Kumar Gandharva.

It is a pleasure to acknowledge the assistance of Sir Vish Krishnan in the above compilation.

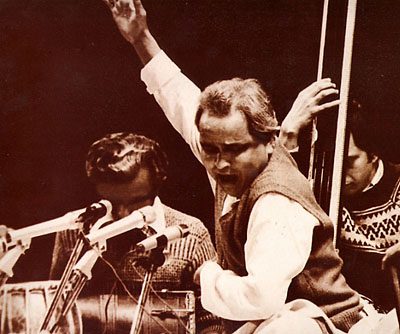

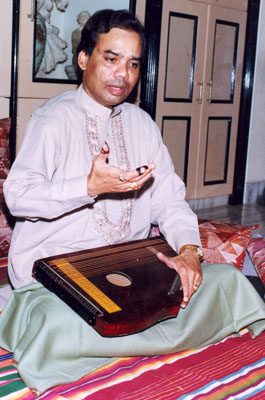

Kumar Gandharva

(From I&B Calendar 2005)

We turn now to the Classical department where we have gathered representative samples of Bhairav and associated melodies. The choice for inclusion of a clip was governed by the following criterion: Does it say something important about the raga, and say it well?

For all its pervasive influence and gravitas, performances in pure Bhairav are few and far between. The dhrupadiyas get the first shot. Nasir Aminuddin Dagar, in a composition set to the 10 beat Sooltala: Shiva Adi.

A comprehensive suite in Bhairav by one of India’s finest musical minds and the greatest living Hindustani composer, Pandit Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang” follows. The first two selections are culled from a public performance in Goa in 1999. Yours truly provides harmonium support and Tulshidas Navelkar plays the tabla.

Jha-sahab, vilambit khayal in Ektala: samajha mana baware.

Jha-sahab, druta khayal in Teentala: bana nahin aave.

The sahitya in Jha-sahab‘s dhrupad-anga composition known as sadra is inspired by Kabir. There’s a deft play on words, and he explains the import.

A sampler of Bundu Khan‘s sarangi where he plays a dhrupad in Chautala. Notice the caress of the komal nishad.

Barkatullah Khan, the grand Senia master of the sitar, is not a familiar name to today’s rasikas. Among his students were Ashiq Ali Khan and Ashiq Ali’s son, Mushtaq Ali Khan. Ah, what ragadari!

A youthful, sprightly Gangubai Hangal.

Kumar Gandharva‘s own composition contains delicate glides and shading of swara. In particular, keep an ear out for graces imparted to the dhaivat: ravi ke karama.

The Bhairav montage concludes with Mallikarjun Mansur‘s sterling display.

We now take up the variations on the Bhairav motif. The commentary from this point on will be terse. A few Bhairav prakars are ‘big’ enough to merit more spacetime than is allotted here. As we make our way through the Bhairav matrix, fix your attention on Bhairavanga, the creative interpolation and extrapolation of its kernel.

Raga Gunakali/Gunakri

In this nominally audav-jati (pentatonic) raga with S r M P d as its swara set, it is not unusual to lace rishab with gandhar along the M->r contour to precipitate Bhairavanga.

Jha-sahab has written a beautiful bandish describing Lord Shiva’s visit to Brindavan to see the baby Krishna. The text verbalizes the Great Yogi’s response to an apprehensive Jashoda.

Mushtaq Hussain Khan of Rampur-Sahaswan.

Kumar Gandharva‘s maverick treatment assigns explicit values to both gandhar and nishad. His own composition: ava mhara mana basiya.

Raga Bairagi

This audav-jati raga employs the following swara set: S r M P n. It was first introduced by Ravi Shankar in the 1940s and was readily embraced by the music samaj. As years went by, through accretion of appropriate melodic gestures it came to be considered a member of the Bhairav stream.

Amir Khan‘s sumarata nisadina tumaro nama is considered representative of the best this raga has to offer.

Incidently, another pentatonic Bhairavanga raga employing the S r M d N set has been advanced in recent times. It goes by the name “Kshanika.”

Raga Anand Bhairav

In this traditional prakar, the komal dhaivat in Bhairav is replaced by its shuddha counterpart. The komal nishad is parachuted into the scheme in an avarohi prayoga S” D n P inspired by Bilawal. In Bhairavanga ragas where either rishab or dhaivat is rendered shuddha, the madhyam tends to assume a powerful role and is often elevated to a vadi swara. Care must be exercised to not let Anand Bhairav stray into Bhatiyar’s neighborhood.

Jha-sahab presents a traditional composition of ‘Sadarang’ and tops it with his own druta cheez.

Jha, vilambit.

Jha, druta.

K.G. Ginde dispenses a smart, taut composition of his guru S.N. Ratanjankar: bina darasa mana tarasata nisadina.

Ravi Shankar‘s handling is exemplary. Notice the hint of komal nishad, not to mention the arresting layakari.

Raga Saurashtra Bhairav

In this uncommon derivate, both dhaivats are pressed into service. The basic idea involves sewing strands of Bhinna Shadaj (G M D N ) onto the Bhairav fabric. In such situations it is not unusual to find divergence in implementation across gharana borders as witness the following two cuts.

Jha-sahab sketches his composition: barani na jaya chhabi.

Ghulam Hasan Shaggan of Kirana.

Raga Mangal Bhairav

In this shuddha dhaivat-laden Bhairav prakar, the nishad is attenuated. Tthere prevails an avirbhava of Durga in the uttaranga via the M P D S” cluster.

Raga Bhatiyari Bhairav

The constituents of this hybrid raga are, as the name suggests, Bhairav and Bhatiyar. Jha-sahab’s design employs shuddha dhaivat only, retaining for the most part the Bhatiyar framework. The Bhatiyaric P G r S is displaced by the Bhairavanga molecule G M (G)r, S.

Pandit Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang” in vilambit Roopak: palaka na lage.

Ramrang’s druta composition: dhurana murana tanana son.

A different perspective is purveyed by Jagannathbuwa Purohit ‘Gunidas’ in his composition rendered here by C.R. Vyas: E aali ri.

Raga Bhairav Bahar

The attributes of a well-designed, wholesome hybrid raga are a judicious choice of the constituents and a smooth transition at the junction of the disparate constituents (Electrical Engineers like to talk of impedance matching in similar situations). Let us see how the various conceptions of Bhairav Bahar stack up.

‘Aftab-e-Mausiqui’ Faiyyaz Khan.

Basavraj Rajguru elaborates on a composition of Achapal (Tanras Khan’s guru): jobana re lalana ko.

Omkarnath Thakur spins a different yarn.

Raga Ahir Bhairav

Among the most popular Bhairav prakars today, Ahir Bhairav admits the shuddha dhaivat and komal nishad. The poorvanga patently hews to the Bhairav protocol, the uttaranga carries elements of Kafi. This is a solid composite and has carved out a swaroopa all its own. The powerful madhyam registers well. A sample chalan is:

D’ n’ r, S, S r G M, M, G M (G)r, D’ n’ r, S

G M P D n D P, D n S”, S” n D P, G M (G)r, r S

Amir Khan‘s deeply introspective mien pervades this piece.

Hirabai Barodekar: rasiya mhara.

Raga Virat Bhairav

A rather busy uttaranga characterises this uncommon raga. The nishad is komal, and both dhaivats are in attendance. The shuddha dhaivat is used sparingly, in special sancharis such as GMPDnDn and PDnS”.

Nivruttibuwa Sarnaik: nayo nayo bairagi.

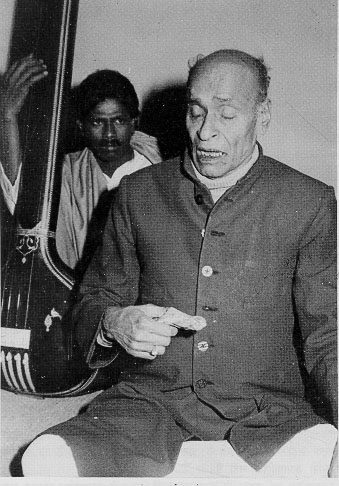

Mallikarjun Mansur

Raga Kabiri Bhairav

This Jaipur-Atrauli specialty also has a busy uttaranga and accomodates both nishads and dhaivats. Notice the lagav of D and n in the avarohi S->D prayoga and the special handling of komal rishab in the tar saptaka. We have two exceptional renditions on tap.

Kishori Amonkar‘s attack on the shuddha dhaivat takes one’s breath away.

Raga Shivmat Bhairav

The twist here lies in the prayogas involving the komal gandhar and komal nishad in an otherwise Bhairav framework. Although the specific nature of their swara-lagav varies across different regions and styles, the general prescription may be summarized in these two tonal strips:

G M (G)r, r g r S

P d n d P

In Jha-sahab’s druta cheez, Lord Shiva finds himself in trouble (again), this time on the eve of his wedding to Parvati. Parvati’s mom strongly disapproves of Him given his appearance. She says to the Great Yogi, “No way Jose! You are not getting anywhere close to my girl.” The G.Y. is taken aback and demands an explanation. But Parvati’s mom will have none of him. Parvati, after all, comes from a high-status family, is convent-educated, enjoys fine dining, loves traveling, movies and rollerblading – a perfect blend of the East and West. The G.Y. isn’t exactly her idea of a studly son-in-law and she says as much:

baurahe ko na doongi apno dulari Girija-kumari

rakhoongi ghara apno

ek na manoongi sikha kahu ki

“Ramrang” byahu na Girija-kumari

rakhoongi ghara apno

Jha-shab, Shivmat Bhairav.

Kumar Gandharva is a bundle of energy.

A different angle from the prism of Vilayat Hussain Khan ‘Pranpiya’.

The pupil follows his guru. Jagannathbuwa Purohit ‘Gunidas’.

And finally, the man who has reified this raga: Mallikarjun Mansur. This AIR recording is a modern classic. The huge meend from P back to S spanning the P->M->G->r->S locus betrays an unusually developed musical intelligence. Alladiya Khan‘s composition is the standard issue to all his Atrauli-Jaipur progeny: prathama Allah.

Raga Devata Bhairav

This raga was brought forth by the influential Agra figure, Azmat Hussain Khan ‘Dilrang.’ Its notable feature is a Bhairavi-like avarohi prayoga via the komal gandhar – M g r S.

(L-R): Azmat Hussain Khan, Alladiya Khan, Nathan Khan

Jitendra Abhisheki, a pupil of Azmat Hussain, and amplifies on the idea.

Raga Beehad Bhairav

A baby of Kumar Gandharva’s, it bears some resemblence to Shivmat Bhairav with its use of both g and n. The distinction lies in chalan bheda and swara-lagav. Kumar sings his own composition: bana bani aayo.

Raga Prabhat Bhairav

The introduction of a Lalitanga through the two madhyams placed cheek by jowl paves the way for an avirbhava of this old raga. The motivated reader will discern the varied flavours emenating from individual temperaments below.

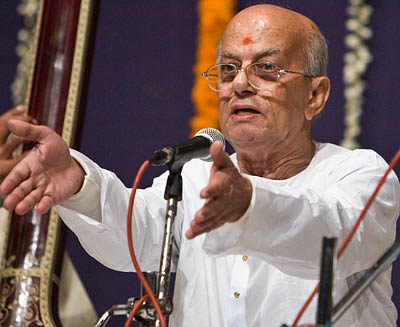

Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang”

© Rajan P. Parrikar

Jha-sahab hauls a traditional ‘Adarang’ composition.

K.G. Ginde volleys Ratanjankar’s bandish in Tilwada: ab to jago manava.

Gangubai Hangal also sings to Ratanjankar’s tune but in vilambit Ektala.

Raga Bhavmat Bhairav

This Lalitanga-laden variant was incubated in the imagination of Kumar Gandharva. The dhaivat is shuddha, and the nishad komal. Kumar himself lays out the preliminaries.

Raga Ramkali

The main plot here involves the insertion of a peculiar tonal phrase m P d n D P into the Bhairav flow. While Ramkali retains the primary Bhairav lakshanas it has its own eccentricities. For instance, there is a predilection for skipping the rishab in arohi prayogas as in: N’ S G M P.

K.G. Ginde presents a traditional khayal ascribed to ‘Sadarang’: machariya mendi suno.

Shruti Sadolikar‘s clip highlights the distinguishing Ramkali phrase. The composition is credited to Alladiya Khan of Atrauli-Jaipur: yeh bana sari raina.

D.V. Paluskar is a class act.

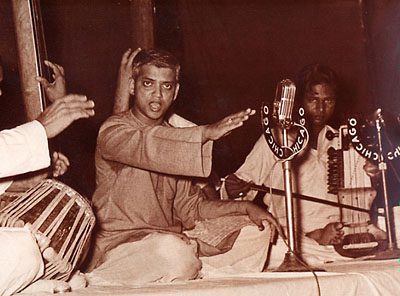

D.V. Paluskar with Ram Narayan on sarangi

(From I&B Calendar 2005)

Pandit Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande has discussed an arcane version of Ramkali that uses both gandhars.

Another idiosyncrasy is observed in the Maihar tradition which eschews the komal nishad. Ravi Shankar‘s resounding alap in this brief segment has a curious feature: the komal nishad manifests itself very subtly (and presumably inadvertantly given the Maihar proscription) as an abhasa (“swara ka abhasa hona” – i.e. when a swara is not consciously intoned but an impression of it is nevertheless created). Zoom in on the region between 0:26 and 0:27.

Raga Roopkali

The raga takes inspiration from Ramkali for its teevra madhyam but there is no komal nishad. An additional feature is the casual hire of shuddha rishab.

Aslam Hussain Khan

Aslam Hussain Khan‘s khayal is launched from that very swara.

Another cut by the Agra elder Khadim Hussain Khan.

Ragas Hussaini Bhairav, Bakula Bhairav, Basant Mukhari, Kaushi Bhairav

These different ragas are grouped together under one header for convenience. They have one common feature in that they share the same scale, corresponding to the 14th Carnatic melakarta, Vakulabharanam: S r G M P d n. But it cannot be emphasized enough that a mere scale does not a raga make. The reader is invited to figure out their respective lakshanas and implementation of the details.

Hussaini Bhairav by Younus Hussain Khan (Pranpiya’s son) discloses a peculiar swoop on the mandra pancham from the shadaj. The Bhairavanga surfaces in the poorvanga.

Bakula Bhairav derives its name from the parent Carnatic melakarta and was conceived by Sumati Mutatkar. In this, her own dhrupad composition, the treatment is Bhairav-like albeit with the komal nishad.

Basant Mukhari emits alternating scents of Bhairav (in the poorvanga) and Bhairavi (in the uttaranga). There are no universally accepted precepts for this raga in its Hindustani adaptation. In some treatments the Bhairavanga is not articulated, whereas in others it is. S.N. Ratanjankar renders his own composition: uthata jiya hooka.

Kaushi Bhairav comes in two varieties. The one considered here is credited to Baba Allauddin Khan of Maihar. This melody stands farther apart from the above three. The theme here is the insertion of Malkauns-anga. The tonal activity is centred on the madhyam. It is instructive to compare Allauddin Khan’s own interpretation with that of his pupil Ravi Shankar.

There is much to be said for Ravi Shankar‘s brilliant, searching mind. He has added to his guru’s theme, expanding the germ of an idea.

Raga Zeelaf

This haunting pentatonic melody is composed of the following swaras: S G M P d.

Jitendra Abhisheki gives a superb account with his own composition. Notice the strong madhyam. Zeelaf also employs the subtle GM->S meend: taba te juga samana.

Raga Devaranjani

This import from Carnatic tradition reveals a vichitra swaroopa. The rishab and gandhar swaras are varjit thus leaving open the wide interval S-M-S. I posted a note on this raga some years ago in the 1990s on the Usenet newsgroup rec.music.indian.classical (RMIC).

K.G. Ginde instantiates S.N. Ratanjankar’s composition.

Raga Nat Bhairav

A relatively recent entrant into the Hindustani catalogue, this melody was popularized by Ravi Shankar. He seized upon the idea after hearing a demonstration of an allied theme by Prof. B.R. Deodhar.

The sampoorna scale employed corresponds to the 27th Carnatic melakarta Sarasangi. The vakra sancharis, however, give it a distinct swaroopa. The Nat phraseology in the poorvanga – S R, R G, G M – is complemented by the Bhairav’s contribution in the uttaranga – G M d, d N S”, N S” (N)d.

Among the finest Nat Bhairavs on record, Vasantrao Deshpande.

Shubha Mudgal sketches an exquisite composition of Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang”: tana mana varun re tope.

Obiter dictum: Basant Mukhari’s scale is also used by a raga known as Hijaj Bhairav but there is a difference of opinion on this issue. Some insist that Hijaj Bhairav is the ancient form of what is today’s Nat Bhairav.

Raga Asa Bhairav

In this hybrid formed by constituents Asa and Bhairav, the Bhairavanga is expressed in the poorvanga, through G M (G)r S. The rest of the contour looks to Asa: S S(M)R M P, DNPD S” and so on.

Ravi Shankar furnishes a delightful play on the theme.

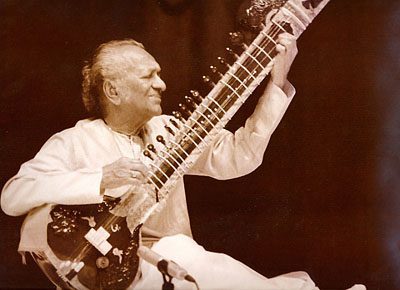

Ravi Shankar

(From I&B Calendar 2005)

Vilayat Khan plays an allied melody called Mand Bhairav where he uses the G M P D N S” pattern of Mand. It is a pile of rubbish, a schoolboy tantrum. He plays the big, fundamental ragas beautifully but is singularly inept at the more ‘complex’ constructions. I do not mean to say this diminishes his stature or musicianship in any way anymore than it does Bhimsen Joshi’s for precisely the same reason. Vilayat’s desire to mount the “me-too-member-of-fancy-ragas-club” bandwagon is understandble. But alas, he has not even a hundredth of the bandmaster’s bandwidth (“bandmaster” is how Vilayat is said to have referred to Allauddin Khan). As regards his much-touted six generations of pedigree, I say, are we talking about music or about Villie-the-Pooh?

Raga Jaun Bhairav

This blend of Ragas Jaunpuri and Bhairav was whipped up by Jagannathbuwa Purohit “Gunidas”. It has a crowded swaraspace – there are two rishabs, two gandhars and two nishads.

Gunidas displays great skill in navigation and manages to successfully bring an aesthetic unity to his design: aba meri suno tuma.

Raga Kalingada

Kalingada and Bhairav share the same scale but there is no Bhairavanga in the former. Kalingada has a flippant mien, its personality far less austere than Bhairav. The gandhar and pancham are advanced to positions of influence, the swara-lagav is mostly linear, without the andolita treatment prevalent in Bhairav. Elements of Kalingada are widely found in many folk forms and in bhajans.

A sample chalan is suggested:

S r G M P, d P M P M G, M G r G

P d P d N, S” N d N, N d P, d P M G M P

A remarkable man of diverse talents and a great master of the harmonium, Govindrao Tembe.

Raga Jogiya

The last item in our menagerie embraces all the swaras of the Bhairav that plus komal nishad. There is little presence of Bhairavanga here. The madhyam is a powerful presence (nyasa bahutva) and anchors the development. The gandhar and dhaivat are skipped in arohi passages.

The following outline clarifies Jogiya’s features:

S r M, M P, P M r S, r S d’ S

M P d S”, S” (N)d P, M P d n d M, M r S

Abdul Karim Khan‘s stirring thumri: piya ko milan ki aasa.

Epilogue

This monograph has brought within its ambit most of the important members of the Bhairav dynasty. A few other traditional prakars such as Bangal Bhairav, Komal Bhairav and so on elude us at this time.

Thinking about Bhairav is a profoundly moving experience. During the course of this compilation, I was often lead to wonder about the great rishis who saw in this primal scale the elemental patterns that finally coagulated into this wondrous melodic organism we now call Bhairav.

These ruminations also brought to mind the great German-English composer Handel. When his oratorio “Messiah” premiered in London to a thunderous ovation, a friend came up and said to him, “All the people seem to be greatly entertained.” Handel, who had spoken of visions of the Lord’s Creation during the making of his magnum opus, was not pleased. He replied, “My dear Sir, I should be disappointed if they were only entertained. My goal was to make them better.” It is hoped that this mighty Raganga Raga Bhairav will inspire similar sentiments in those whose good fortune it is to make its acquaintance.