First published on SAWF on May 28, 2001

Introduction by Rajan P. Parrikar

Rajan P. Parrikar (Colorado, 1991)

Namashkar.

Among the refrains of my childhood were the hymns of veneration sung by my elders to Goa’s musical luminaries. Four names stood out, exalted above the rest, their accomplishments stirring devotion almost divine: Kesarbai Kerkar, Mogubai Kurdikar, Dinanath Mangeshkar, and Khaprumama Parvatkar. Yet, even in this pantheon, Khaprumama’s name often rose to singular heights, evoked with a fervour that set him apart.

Some of those admirers, now long departed, had personal connections with Khaprumama. Few among them could fully grasp the intricacies of laya or fathom the profound breadth of his command over laya-shastra. Yet they recognised the magnitude of his genius, cherishing the privilege of having crossed paths with this extraordinary figure.

Khaprumama, born in 1879 in Parvat, near the village of Paroda, dedicated his entire life to the study and mastery of laya-shastra — the science of tempo, its divisions, and rhythmic structures. While the principles of this discipline are deceptively simple to state, their exploration swiftly ventures into realms accessible only to the rarest intellects. A parallel might be drawn with Number Theory in pure mathematics, where seemingly elementary propositions yield to solutions only in the hands of the supremely gifted.

What set Khaprumama apart, even among the greats of tala-shastra, was his unmatched ability to simultaneously hold multiple rhythmic cycles in his mind and synchronise them with effortless precision. A kindred spirit in this rarefied faculty was Johann Sebastian Bach, whose genius lay in weaving intricate counterpoints across multiple melodic lines in the Western classical tradition.

In the late 1970s, the Kala Academy in Panjim was privileged to count the illustrious Tabla maestro, Taranath Rao Hattangady, among its faculty. It is among my most treasured memories to recall the many stories Taranathji shared with my brother and me about Khaprumama, illustrating the dazzling rhythmic puzzles that this maestro had conjured and resolved.

Today, the memory of Khaprumama has all but faded, an occupational hazard for those who operate within an oral tradition. He left no written record to bear witness to his astonishing abilities. Nor did a critical mass of students emerge to carry forward and propagate his revolutionary contributions. When his mortal remains were consigned to the flames, so too was the vast library of knowledge he embodied — a conflagration that erased a lifetime of unparalleled achievement. What remains as a testament to his genius is the archive of recordings below, an enduring homage to the feats of this rara avis.

The profile on Khaprumama presented below is taken from an anthology in Marathi entitled Kalaatm Gomantak (“Talented Goa”) by the late Shri Gopalkrishna Bhobe. It has been skillfully rendered into English by Dr. Ajay Nerurkar. The first public release of this transcript was on the Usenet newsgroup rec.music.indian.classical (RMIC) in 1996.

Excerpts from Prof. B.R. Deodhar‘s essay from his book Pillars of Hindustani Music are also reproduced below.

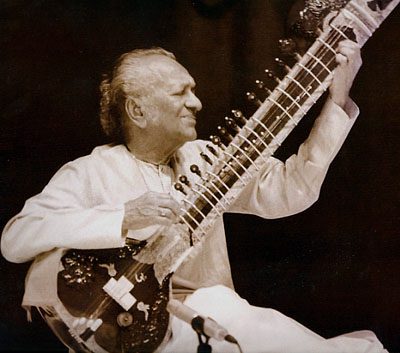

Also included below is a tribute to Khaprumama by one of the world’s most eminent musicians, the sitar maestro Ravi Shankar. It was specially taped for this feature on May 19, 2001 at Ravi Shankar’s home in southern California. We thank Smt. Sukanya Shankar and Ravi Shankar for their gesture.

Warm regards,

Rajan P. Parrikar

“LayaBhaskar” Khaprumama Parvatkar

by

Gopalkrishna Bhobe

(Translation: Dr. Ajay Nerurkar)

Without mental acuity it is impossible to touch the core of laya – rhythm with all its different facets. The swara can be mastered with effort, but the sense of laya has to be inborn. Even venerable ustads are in awe of it. Those who are able to conquer both the swara and laya can be said to have understood the very essence of music. A lifetime’s ardent devotion may be enough for someone to acquire sway over the swara but more than a bookish knowledge of laya may still elude him. To perform the miracle of laya, one needs to have it in one’s blood, and thus blessed performers instantly acquire fame and admiration.

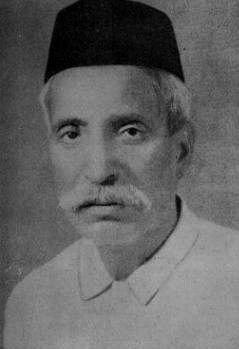

Khaprumama Parvatkar (1879-1953)

Not too long ago, in Goa there lived a person who had not only touched the core of laya but had achieved a sort of enlightenment in this art. He immersed himself in the acquisition of this divine learning and as a result was able to grasp tala in its entirety. This ascetic-musician could have gained the immortality of an Amir Khusro, a Tansen, a Sadarang or a Pakhawaji Bhagwandas had he been in the court of an aesthete ruler in an earlier age. A university would have been built around his work, volumes written on his discoveries. These books would then have become the Word of God to future generations.

His name was “LayaBrahmaBhaskar” Khapruji Parvatkar. To his dying day, Khapruji devoted himself to the study of laya, unencumbered by any triumphal ambition. The only opponent he wanted to subdue was the power of laya. In the process every part of his body had imbibe rhythm, as it were. Much as a sadhu would teach theology to his disciples by peeling away the skin to reveal what lay inside, Khapruji brought the science of laya under control and then simplified its most unfriendly aspects so that everyone could comprehend the substance of this profound body of knowledge.

Khaprumama was like a living almanac of laya. He knew its minutest details. It is doubtful whether there has been another like him in India. Upon greater thought, one feels certain that he was infact in a class by himself. Unfortunately, he did not record his achievements systematically, so that today we can do no more than say that once upon a time Goa had produced such a person. The generation that saw and heard Khaprumama was lucky and the ones who knew him closely were truly fortunate.

I can still clearly remember how I first met Khaprumama.

Khaprumama was born in this house in Parvat, Goa

It was Holi Poornima. The brightness of a fourteen-wick lamp was competing with the full moon as the devotional song Shri Bhagwanta yaadavanchya raaya ho began. Musicians from around were present and were standing in a circle playing in unison various kinds of drums, triangles and mridangams. The sam was on the first syllable of Bhagwanta.

A visiting ghumat (a type of drum) player eager to show his skill, delicately played a mukhda, followed it up with a paran and attempted to catch the sam. As luck would have it, he erred in the mukhda and missed the sam. The audience laughed mockingly. This offended the visitor and a debate began between his side and the others. Wiser heads prevailed when this argument threatened to take a serious turn. They pleaded, “Let us not disrupt the worship. We can refer the issue to Khaprumama tomorrow and have him adjudicate.” The proceedings resumed albeit with some misgivings on both sides.

The next day Khaprumama was in the village. He was wearing a flat, grey cap, a collarless Parsi-style coat, an ordinary dhoti and Kolhapuri chappals. His snow-white moustache attracted my attention first. The half-closed eyes attested to his being deep in thought. Khaprumama pronounced his verdict which everyone joyfully accepted and the festivities continued. I also got to see with what ease his hands moved over the ghumat and the solid sound they made.

At a later time, I had the opportunity to see him demonstrate various examples of his layakari at the music school of his student, Vishwambar Parvatkar. Ever since understanding what laya was, I had heard a lot about Khaprumama’s miraculous layakari. I was not much impressed by what I saw before the actual performance got under way. But once that happened, I was speechless, dumbfounded by the unbelievable display.

A chakradhar with five dha’s, some others with seven, eight, nine, ten, fifteen, twenty, all the way upto thirty five and forty dha’s, proceeded from his mouth as Vishwambar held the theka. After this came some arithmetical tricks like adding whole and fractional matras, subtracting, multiplying or dividing them. However, I was truly wonderstruck when he played the sixteen-beat Chitaal on the tabla and at the same time recited the fourteen matras of the Chautaal theka, the two of which he then managed to bring to the sam synchronously. There was more – he played a chakradhar from a tripallavi on the tabla as he vocalised it in reverse and, of course, brought them simultaneously to the sam. I was humbled by this enormous wisdom. To this day I have not heard of anybody else reproducing these exploits. And it is doubtful whether this will ever happen. Such divine performers are born but once in a hundred years; and they take their amazing gift with them when they depart.

Khaprumama was born in ‘Parvat’, a village lacking all the conveniences of modern life. On a hilltop was a temple with a self-existent linga of Shri Chandreshwar (Lord Shiva) and surrounding this were 16-17 houses with brick-lined roofs. This was the entire village community. Residents had to walk four miles down a twisting and turning road to Parode to shop for necessities. But by the grace of Shri Chandreshwar every house in this village has produced extraordinary musicians.

Chandreshwar-Bhutnath temple in Parvat, Goa

The famous singer Dulubai Parvatkar hailed from here. Smt. Mogubai Kurdikar was from around here too. Other names include Harishchandra Parvatkar, an excellent pakhawaji, Shaamba Parvatkar, Raghuvir Parvatkar, Balkrishna Parvatkar, all expert sarangi players. In the present generation, there are musicians like Dattaramji Parvatkar who has made a name for himself as a sarangiya.

Khaprumama was born around 1878-79. His given name was Lakshman. However, his mother lovingly called him Khapru and this name stuck. In the early years of his life, Khaprumama used to play the sarangi. The Kalavant community of Parvat filled their days with music and dance. This festive atmosphere moulded the minds of the children there. They built up an intimate relationship with all the musical instruments and could then easily master any instrument of their choosing. Khaprumama received his preliminary training on the sarangi from his uncle Raghuvir Parvatkar and on the pakhawaj from his cousins Harishchandra and Ramkrishna Parvatkar.

While learning to play the tabla the young boy wondered why, when a tempo can be speeded up twice, thrice or four times, it should not be possible to achieve a fractional speed-up. On asking elders about this, he was told to not concern himself with such matters and concentrate on the straight and the narrow instead. But this did not satisfy Khaprumama’s searching mind. He began to research and found himself so rivetted by this new field of study that this was all he did all day long. He forgot himself. Immersed in laya, he spent days, weeks and even months pondering over knotty questions of tala-shastra and theorizing about them.

Khaprumama’s recordings

Khaprumama successively divides the 16-beats Teentala into 9, 10 and 11 matras following up each sub-division with its dugun (doubling in speed) as well as a short composition for each take.

Khaprumama successively divides the 16-beats Teentala into 13, 14 and 15 matras following up each sub-division with its dugun (sometimes also chaugun) as well as a short composition for each take.

Khaprumama recites the bols of the 12-beats Ektala within a Teentala cycle of 16 beats, successively increasing the number of avartans of Ektala within the 16-beats cycle.

Khaprumama spells out some darje in Teentala.

The recordings for the first two clips above were made available by Madhav Pandit of Margao, Goa.

At a music symposium organised by the late Pt. Vishnu Digambar Paluskar in 1919, Khaprumama presented, for the first time, his solutions to some of the most intricate riddles in the science of tala. Many learned tabla and pakhawaj players assembled there saluted him. The late Pandoba Gurav Waikar (a disciple of the famed Nana Panse of Indore) who considered himself an authority in this field, spontaneously declared, “Khapruji, you have no equal. Only you have achieved true enlightenment in this art!”, when Khapruji effortlessly answered a query he had raised.

In 1921, Khaprumama’s rendering of various aspects of layakari regaled all those present at a mehfil organised by Pt. Bhaskarbuwa Bakhale. Panditji himself commended him with the words : “Khapruji, you reign supreme in layashastra“.

In 1933, Bombay was the site of a mammoth mehfil. SangeetSamrat Khansaheb Alladiya Khan, Khansaheb Vilayat Husain Khan, Aaftaab-e-Mousiqui Faiyyaz Khan and other well-known vocalists, instrumentalists and tabla players had gathered. Some of the tabaliyas casually challenged Khaprumama to “produce a theka of thirteen beats and play it at the tempo of a twelve beat theka“.

Khaprumama had privately done hundreds of such tricks. He did not find this much of a challenge at all. He not only built a thirteen matra theka but also topped it off with a tiha’i. The tabaliyas who had intended to poke fun at him were astonished. Even Alladiya Khan couldn’t contain himself. Overcome with emotion, he exclaimed, “Good Lord ! I bow my head a hundred times before your learning.”

At another such mehfil Khansaheb Aman Ali blurted out, “Amaa, my entire existence shall henceforth revolve around your laya”. Khaprumama had produced a composition having a tiha’i with three dha’s around a theka of 13.5 beats. A Hyderabadi tabaliya there fell at the feet of Khaprumama with tears in his eyes.

In 1935, Mogubai Kurdikar had a statue made of him and ceremonially handed it to Khaprumama. On this occasion some distinguished ustads from Hyderabad, after analysing his mastery over laya, honoured Khaprumama with the title “The Shining Sun of Laya”. Later, in 1939 artistes from Bombay feted him in what was a celebration of a lifetime’s devotion to music. It was a celebration graced by the presence of the SangeetSamrat himself. Khansaheb Alladiya Khan presented him with the title “LayaBrahmaBhaskar.” At a small function in his home-state of Goa, music lovers decorated him with the title “TalaKanthaMani” (The glittering jewel in the crown of tala). He was also honoured in a ceremony in Poona with Barrister Babasaheb Jaykar in the chair.

Khaprumama was a proficient sarangi player, singer and pakhawaj player as well, but his obsession with laya forced him to give up everything else. He lost himself in the universe of rhythm. He occupied his mind with exercises such as : play a tala at a particular tempo, slow it down by half, by a quarter, speed it up by a quarter, by a half, by three-quarters, then add half a beat, perhaps a quarter-beat and so on. He occupied himself so thoroughly that he abstracted himself from his surroundings. He became oblivious of sensations like hunger and thirst. In the middle of a bath, he would think of something and without bothering to wipe himself dry, would come out, Archimedes-like, in the nude. Towards the end of his life, to use whatever was convenient – his lap, chest or head – to mark time, and fill in the bols within the matras, became a daily routine.

The ParaBrahma tala with 15.75 beats was a one-of-a-kind creation of his. He made it complete in all respects. Around this tala he weaved a MahaSudarshan paran, an extremely difficult tabla composition, that had 125 dha’s. Cognoscenti of tala couldn’t believe their ears when they heard it. This feat carried his fame all over the country.

In perfecting this tala, laya imbued every pore in his body. Deep in sleep, he would move his hands over the floor or on the board, as if playing the MahaSudarshan paran.

He knew thousands of mukhdas by heart. He himself had composed hundreds of gats, relas, todas and parans. An attempt to describe his variations on the talas would require an epic of the size of the Mahabharata.

He was of generous nature. Someone wanting to learn a mukhda or a bol would be taught four or five mukhdas and gats. He would tirelessly toil to get through to those who came to learn from him. He was untouched by the paranoia that someone might steal his knowledge. Whoever approached him was wholeheartedly given what he wanted. He was as much of a giver as he was learned. He had the capacity to establish a gharana of his own, much like Pt. Ram Sahay‘s Banaras gharana, but an entire Banaras had stood behind Pt. Ram Sahay and he had been revered as a saint. This was not the case with Khaprumama. There were oral praises sung to his devotion to his art, but such praise is evanescent. Nothing enduring was ever done.

Such was this LayaBrahmaBhaskar, ever affectionate and humble at heart, never failing to earnestly enquire after one’s well-being even in the course of a small chat in the street. Even while speaking, his entranced eyes were proof of the spell laya had cast over him. When made aware of the betel juice that had trickled down from his mouth he would brush it off like it were dirt and with his fingers fidgeting, plod on.

The other day Thirakhwa Saheb said — “O to Laya ke auliya thhe” (He was a prophet of laya). The Young India Gramophone Company made recordings of him. They must be a treasure to those who possess them today. The Young India company is now no longer in existence and with it these recordings have also vanished.

Just before his death Khaprumama had lost consciousness. He was unable to swallow even his medicine. But his body was busy tackling some mysterious laya conundrum. He was muttering something unintelligible. And on the Third of September 1953, this rare, noble sage’s soul became one with Laya, taking with it all his propositions, theorems and the miracles he performed with laya. His uncommon achievements were lost for ever much like the spirit of an age dies with it.

…I requested [Khaprumama] to give a demonstration which he readily agreed to give. He clapped out the beats on one hand and starting with the (standard) four claps, he produced respectively 3, 5, 6, 7 up to 16 beats (in the basic interval) with perfect precision. I asked him, “Would you be able to do 17 beats in the space of 4?” “That is nothing,” he said, “I can not only do 17 but as many as 64.” To my amazement he did so. Then he started playing trital (a tala of 16 beats) on his hand. Simultaneously, while he clapped out the sixteen beats on his hand, he went on to recite the bols of all other talas including – ektal, dhamar, zaptal and sawari. The bols invariably started from the first beat of the tala chosen and promptly terminated on the sam of that tala; all the while, the tala clapped out on his hand continued to be trital. After this he started sawari (a tala of 15 beats) in place of trital while reciting the bols of dharnar. The individual sams of the two talas were placed with complete accuracy. Thereafter, while continuing to beat out sawari with his hands, he went into numerous even and odd variations of the tempo of dhamar bols. Finally, to cap it all, while continuing to play sawari in the standard rhythm on his hand he recited the improvised bols of dhamar in a variety of rhythms.

Only those who are masters of the percussion art will realize how difficult it must be to achieve such complete proficiency in the arithmetic involved. When I requested him to demonstrate other interesting things he performed another amazing feat. He started counting out on his hand the 12 beats of chautal, and simultaneously proceeded to recite the bols of dhamar (14 beats). Gradually in place of the basic chautal rhythm being clapped out by his hands he introduced the bols of chautal while continuing to recite the bols of dhamar. This was followed by replacement of the standard rhythm of dhamar by the improvised bols (padhant), of dhamar. Rhythmically, the clapping and recitation of bols were completely unrelated but both were true to their respective talas and the two time cycles accurately terminated on their sams. It might be clear to the reader by now how difficult the whole exercise must have been. I asked him, “Mama, I hear that you perform another impossible feat, viz. to stamp out two different talas by your feet, a third and fourth tala with your two hands, and simultaneously recite the bols of a ‘fifth tala. Is that true?” He said, “Just watch me – I shall demonstrate it to you.” With his left hand he proceeded to beat out the (16 beat) trital, with the right foot zaptal (10 beats), with his right hand dhamar (14 beats), with his left foot chautal (12 beats) while reciting the theka (standard or basic bols) of sawari (15 beats). The five different time cycles accurately terminated on their respective sams without any obvious effort on his part but I found it most taxing to watch what he was doing on all five fronts. The readers might now be in a position to understand the kind of mastery Khaprumama had achieved in the field of layakari…

… Each tabala player proceeded to demonstrate by clapping what was enjoined by his particular tradition. Several minutes passed but there was no sign of the discussion coming to an end. I was wondering how best to put a stop to the wrangling. An idea struck me. I respectfully said to them, “You are all experts in your field but I have one small doubt. You are clapping out the beats and reciting the bols of your tala. Would they synchronize perfectly with the metronome?” Some of the tabala players indignantly said, “Do you take us for some half-baked tabala players? Bring along your metronome and see whether we keep pace with it.” I sent for the metronome, wound it up and set it in the rhythm they indicated. Each tabala player proceeded to clap out the tala while reciting the bols. But they themselves noticed that within a few minutes the strokes of the metronome and their clapping were not perfectly synchronized. When the expert tabala players discovered that they were not able to stick to their rhythm and recite the bols accurately when measured against the instrument, they began to retrace their steps to the auditorium one by one. Only Khaprumama stayed behind. I placed the metronome before him. He said, “Others could not manage it. Let me try it.” He, like the others, started clapping out the rhythm and reciting the bols. He went on doing it for two or three minutes but there was not the slightest lack of synchronization between his claps and the strokes of the metronome. I tried to run the instrument faster, then slower but Khaprumama’s timing and the strokes of the metronome were identical. It was an amazing demonstration of his mastery of rhythm!…

Acknowledgements

– Dr. Ajay Nerurkar

– Arun Parvatkar (ex-Librarian, Kala Academy, Goa)

– Ravi Shankar

– Sukanya Shankar