by Rajan P. Parrikar

First published on SAWF on October 16, 2000

Rajan P. Parrikar (Boulder, Colorado, 1991)

Namashkar.

In this article we present a review of the book Raga Malhar Darshan by Dr. Geeta Banerjee. The material for this publication evolved from her doctoral work at Allahabad University completed under the supervision of her guru Pandit Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang.” Dr. Banerjee has been a longtime performing vocalist and was on the Music Department faculty at the University. Following Jha-sahab’s retirement she succeeded him as Head of the department. She is now retired from active duty but maintains a part-time appointment.

Raga Malhar Darshan represents a summary of a thorough investigation of Raganga Malhar and its derivatives. The organization of the subject matter is chronological, and three major time periods are identified in the development of the Malhars: prachina (before the 15th C), madhyakalina (15th C – 18th C) and arvachina (19th C to the present).

Ragas Shuddha Malhar, Megh Malhar and Gaud Malhar belong to the first period. Many of the Malhars we relish today fall to the second lot. The treatment is comprehensive, a product of first-rate scholarship. Although the title bears the name of only one author it is clear that the shastraic backbone and many of the insights are due in no small measure to Jha-sahab himself.

Chapter 1, titled “Raganga Raga Malhar or Raga Shuddha Malhar,” cuts straight to the core. The paterfamilias, Raga Shuddha Malhar, is traced historically as it occurs in the ancient texts such as Sangeet Ratnakara, Sangeet Parijat, Raga Manjiri, Sangeeta Darpana, Raga Tarangini and a host of other treatises. The attendent views of the author-pandits are recorded and critiqued. This historical section is followed by a detailed musical analysis of the Raganga Raga Shuddha Malhar. Just what it is that constitutes the Malhar anga is fleshed out. Comparisons and differences are drawn with two other ragas – Durga and Jaladhar Kedar – that employ the same pentatonic scale S R M P D, where M = shuddha madhyam. Throughout the volume every theoretical discussion of a raga culminates in a collection of notated compositions: dhrupads, khayals and taranas, old (‘traditional’) and ‘new’ (mostly Ramrang’s compositions).

Chapter 2 lays the groundwork for the time-framed Malhar prakars of the chapters following.

Chapter 3 discusses the prachina prakars.

Chapter 4 addresses the madhyakalina period.

Chapter 5 deals with the arvachina ragas (see Footnote for the names of the actual ragas covered).

The major prakars are put under the lens and analyzed; their variations are also dealt with. For instance, Gaud Malhar has a less-familiar version that deploys komal gandhar, Nat Malhar comes in two flavours, one of them with both gandhars, and the more common type with only shuddha gandhar. A distinction is drawn between Megh and Megh Malhar and variations of the latter are fleshed out. The compositions are for the most part offered only in the principal versions (so determined by the author’s background).

In Chapter 6 the sampoorna jati Malhars are assessed.

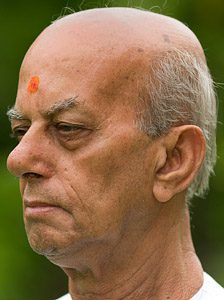

Geeta Banerjee and Ramashreya Jha

in Goa (2000)

Chapter 7 reviews a few recently-hatched (i.e. conceived by Ramrang) Malhars and their compositions.

The concluding Chapter 8 contains a brief discussion on rasa and its realization in the different Malhars.

There have been other published works dedicated to the Malhars. For instance, the volume Malhar Ke Prakaar by Jaisukhlal Shah, which contains some useful traditional compositions but is otherwise a rather sloppy piece of work and called as such by Dr. Banerjee in her prefatory remarks. Pandit Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande gives a detailed discussion on the Malhars in his magnum opus, Hindustani Sangeet Paddhati, from which Dr. Banerjee has freely drawn on.

Two features of Raga Malhar Darshan make it particularly outstanding. One is the assemblage of many traditional compositions many of which are not easily accessible. Furthermore, Jha-sahab’s own compositions are a testament to his creative genius and stature as one of the preeminent Hindustani vaggeyakaras of our time.

Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande

Of particular profit to the serious student or performer is the methodology of raga analysis that is proposed. The reader is introduced to the shastraic language and familiarized with the kind of critical thinking necessary for an inquiry into the innards of a raga. Jha-sahab’s earlier volumes demonstrate well this approach where the raga is taken apart swara-by-swara and then re-constituted. Although Jha-sahab’s pedagogic virtuosity and analytical acumen are fomidable, he credits Bhatkhande for “showing me the way.” But Ramrang is no uncritical follower, no “lakeer ke faqeer“. In a recorded conversation with Satyasheel Deshpande, Jha-sahab leaves no doubt of the debt owed Bhatkhande. That conversation brings to mind a moving passage that Satyasheel’s father, Vamanrao Deshpande, wrote decades ago concerning his first meeting with Chaturpandit Bhatkhande:

“…Around this time Panditji was terminally ill with cancer. Once I expressed a desire to be introduced to Panditji and Bhal with great alacrity took me to his bungalow at Walkeshwar. Panditji was lying on his back on his bed, beneath a window in the ground floor room, with both arms on his chest. Bhal introduced me saying, ‘He is an Accountant – also practises music’ and seated me on Panditji’s bed. Panditji stroked me on my back and said, ‘Educated people should take an interest in music. Continue working hard at it. You will find our Bhal very useful.’ I consider the touch of his hand on my back as one of the most significant happenings of my life. I also consider that my subsequent progress in music and whatever little I wrote on the subject is a direct fruit of his blessing…” (Between Two Tanpuras).

A translation of a passage from Raga Malhar Darshan illustrates a typical analysis. Similar analyses are to be found in Jha-sahab’s own volumes.

On the swara prayogas in Raga Megh Malhar:

“Shadaj apart, the rishab occupies an important position in this raga, both in arohi and avarohi movements. Despite its ‘deergha bahutva‘ role in Megh Malhar there can be no nyasa on the rishab. That swara is almost always andolita and looks to madhyam for assistance. To wit, S (M)R (M)R, M R R, n’ S. The rishab‘s position in Megh Malhar is precarious. It cannot be elongated for the Megh Malhar swaroop to come through. If rendered stable (“sthira“) it runs the risk of losing itself to Sarang. And because it is kept andolita with the assistance of madhyam it cannot establish an identity of its own. To strengthen the veera rasa component of the raga, rishab is also used in the ‘alanghan bahutva‘ role. This mixed mode use is seen in the following passage:

(M)R (M)R M P (andolita) and P M R M, (M)R (M)R S (mixed).

The rishab swara is never skipped, for it is the ‘mukha swara‘ of the raga. In those cases where the intonation of a particular swara immediately suggests the raga identity the said swara is known as the ‘mukha swara.’ The rishab of Megh Malhar and the gandhar of Darbari are such examples…”

The remaining swaras in Megh Malhar are similarly illuminated and the raga is then put back together. These tools of raga analysis should be part of every serious student’s armoury, for they give insight into the raga’s genetic blueprint. At a later point in time I will post clips, time and weather permitting, of this swara-by-swara dissection demonstrated by Jha-sahab in delineating the scale-congruent Ragas Megh, Megh Malhar and Madhmadh Sarang. [Update: Listen to it here.]

Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang”

(© Rajan P. Parrikar)

Two areas for improvement suggest themselves. An index at the end of the volume would have been useful. If Jha-sahab can be pursuaded to record a CD-ROM of the outlines of all the compositions in the book, that would constitute a document of immeasurable archival value.

A few samplers of the bandishes in the book are now offered. Jha-sahab sings his composition in Raga Gaud Malhar: jhingura jhanana jhanakara.

The following two clips are in Raga Chhaya Malhar.

Ramrang first provides an outline of the composition (of Kunwar Shyam) as received from his guru, Bholanath Bhatt: sakhee Shyama nahin aaye.

And the same composition by Bhimsen Joshi.

The final clip is a traditional composition in the uncommon Raga Arun Malhar, in Ramrang‘s voice: kaha na gaye saiyyan.

For a discussion on Ragas Chhaya Malhar and Arun Malhar, see A Tale of Two Malhars. A medley of Ramrang’s compositions may also be found in Ramrang – A Bouquet of Compositions and A Stroll in Ramrang’s Garden.

Raga Malhar Darshan (1999)

Pratibha Prakashan

(Oriental Publishers and Booksellers)

29/5, Shakti Nagar

Delhi 110007

INDIA

Telephone: 91-11-7451485

Price: 800 Indian rupees

Dr. Banerjee has authored two other books that serve as adjuncts to Jha-sahab’s 5 volumes of Abhinava Geetanjali.

Abhinava Geetanjali (Vol 1-5) by Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang.”

Raga Shastra, Parts 1 and 2, by Geeta Banerjee.

Publisher for Abhinava Geetanjali and Raga Shastra:

Sangeet Sadan Prakashan

134, South Malaakaa

Allahabad, INDIA

Telephone: 91-9935725812

Email: sangeetsadanprakashan@gmail.com

Footnote

(Ragas in Raga Malhar Darshan)

Chapter 1 (Raganga Raga Malhar):

Shuddha Malhar

Chapter 3 (prachina):

Megh, Megh Malhar

Gaud Malhar

Chapter 4 (madhyakalina):

Miyan Malhar

Soor Malhar

Ramdasi Malhar

Nat Malhar

Mirabai ki Malhar

Dhulia Malhar

Gaudgiri Malhar

Charju ki Malhar

Jayant Malhar

Chapter 5 (arvachina):

Samant Malhar

Chanchalsas Malhar

Arun Malhar

Roopmanjari Malhar

Chhaya Malhar

Tilak Malhar

Sorath Malhar

Des Malhar

Sveta Malhar

Nayaki Malhar

Kedar Malhar

Jhanjh Malhar

Chandra Malhar

Chapter 7 (nava-nirmita)

Mahendra Malhar

Anjani Malhar

Janaki Malhar