by Rajan P. Parrikar

First published on SAWF on June 11, 2001

Rajan P. Parrikar (San Francisco, 1989)

Photo by: Dr. Anand Bariya

Namashkar.

Our incurable wanderlust through ragaspace now anchors at an illustrious port of call: Raga Asavari. Possessing the cachet of an elemental raga, Asavari has profoundly shaped the Hindustani musical imagination, casting its enduring spell over centuries. This installment undertakes an exploration of this luminous melody and its melodic progeny — the Asavariants, as I like to call them.

Raga Asavari, along with its kin, Raga Gandhari, is steeped in antiquity, with both finding mention in Sarangdeva‘s seminal treatise, Sangeeta Ratnakara. Pandit Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande, in his magisterial Hindustani Sangeet Paddhati, meticulously parses through the labyrinthine raga nomenclature and structure, elucidating their evolution through time with the precision of a jeweller appraising gemstones.

Bhatkhande’s exhaustive work sifts through conflicting accounts in ancient texts, unravelling, where possible, the Gordian knots that have tangled raga taxonomy over centuries. For the historically inclined, his magnum opus is a treasure trove. Here, however, we shall focus our lens on contemporary musical practice and the enduring splendour of Asavari in its present form.

Throughout this discussion, M = shuddha madhyam and m = teevra madhyam.

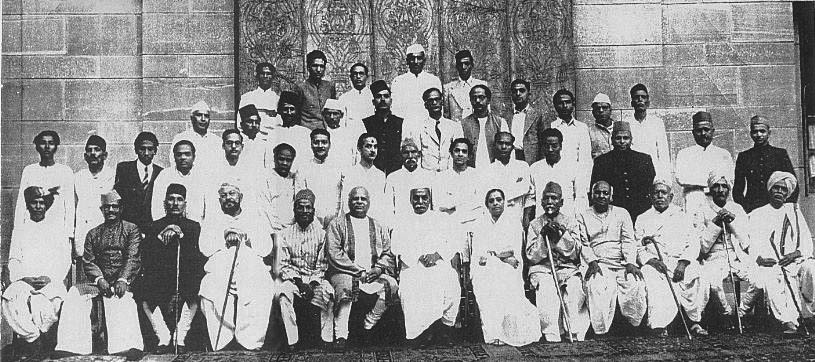

Group photograph with Indian President Rajendra Prasad (c. 1950)

Front row, sitting (l-r): Unknown, Nissar Hussain Khan, Ahmad Jan Thirakhwa, Hafiz Ali Khan, Mushtaq Hussain Khan, Omkarnath Thakur, Rajendra Prasad (First President of India), Kesarbai Kerkar, Allauddin Khan, Kanthe Maharaj, rest in the row unknown.

Second row (l-r): Ghulam Mustafa Khan, unknown, unknown, Keramatullah Khan, Radhika Mohan Moitra, Illayaz Khan, Bismillah Khan, Kishan Maharaj, unknown, Ravi Shankar, Ali Akbar Khan, Vilayat Khan, Narayanrao Vyas, Vinayakrao Patwardhan, D.V. Paluskar.

Third row (l-r): First four not known, Ghulam Sabir Khan, S.N. Ratanjankar, Gyan Prakash Ghosh, next four unknown.

Fourth row (l-r): Unknown, Vinaychandra Maudgalya, next three unknown.

Raga Asavari

Asavari denotes a that, a raganga and a raga. The Asavari that, introduced ad hoc by Bhatkhande as one of his 10 basic groups, represents the scale corresponding to the 20th Carnatic melakarta Nata Bhairavi: S R g M P d n. The raga, Asavari, itself comes in three flavours, each distinguished by the deployment of rishab. They are, respectively, the shuddha rishab-only (R) Asavari, the komal rishab-only (r) Asavari, and the third type employing both r and R. The swaras of the R-only Asavari are aligned with Bhatkhande’s Asavari that proper whereas those of the r-only Asavari align with the Bhairavi that.

Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande

The oldest version is the r-only Asavari and it is the preferred choice of the dhrupadiyas. The switch to the R-only is relatively recent and has come about through the agency of the Gwalior school. Bhatkhande alludes to the khayals by the Gwalior pioneers Haddu Khan, Hassu Khan and Natthu Khan in support of this claim. This shift to the augmented rishab facilitates fast tans so dear to khayaliyas in contrast to the original S r M movement. Bhatkhande observes that the dhrupad performers of Rampur favour the r-only Asavari. However, he also records, and this will be borne out when we hear Allauddin Khan later, that he heard Vazir Khan render Asavari with both the rishabs.

The aroha-avarohana set for the r-only Asavari is:

S r M P (n)d, (n)d S” :: S”, r” n d P, d M P (M)g, r S

The shuddha rishab Asavari is obtained by appointing R in lieu of r in the above contour. The essential features of Raga Asavari and Asavariants such as Jaunpuri, Gandhari and Devgandhar are contained in raganga Asavari. In the discussion below, we illustrate the lakshanas with the r-only Asavari.

S r P (n)d, d M P (M)g, r S

The key idea here is avarohi movement from P to g with only a hint of M (langhan alpatva). Neighbourly amity between r and g must be held in check, for a potential tirobhava (disappearance of raga swaroopa) due to Todi lies in wait (see The Empire of Todi for details of raganga Todi).

M P (n)d, (n)d S”, r” n d, P, M P n d, P, d M P (M)g, r S

The langhan alpatva of n en route to the shadaj in arohi movements is an Asavari signpost. The dhaivat and pancham are locations of repose (nyasa bahutva). The gandhar is also a nyasa swara but less so than P and d. Notice the Bilaskhani Todi-esque descending contour. The prescribed pause on P from d puts paid to any Bilaskhani aspirations.

That was the gist of the Asavari raganga, according to Hoyle. Not every subtlety and nuance can be conveyed or put down in words. While we do not wish to make light of the details, our guiding philosophy is that espoused by Einstein: “I want to know God’s thoughts; the rest are mere details.”

Obiter dicta: An oft-heard phrase, P M P S” (n)d P, serves as a conduit for uttaranga forays. The uccharana (intonation) of M P (n)d above radically differs from that in Darbari (see The Kanada Constellation). The motivated reader is encouraged to think up possible tirobhava combinations brought on by Bhairavi. Although a kosher Asavari omits the nishad in arohi prayogas, it is sometimes solicited in clusters around the shadaj, the tar saptaka shadaj in particular. To wit, n S” or n S” r”.

Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang” takes us on a guided tour of Asavari. In him are joined the twin virtues of clarity of thought and gift of expression. The exposition was taped via long-distance telephone and reins in all the points made above and more.

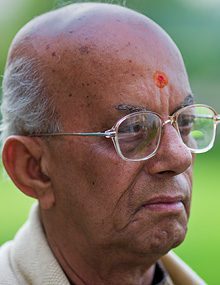

Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang”

(© Rajan P. Parrikar)

Jha-sahab’s fifth volume of Abhinava Gitanjali, long overdue, will be off the press within the next 2-3 weeks. A complete discourse on Asavari is among the contents. (Update: The fifth volume is now out.)

A superb cast of clips awaits us as we ring up the curtain in the classical theatre. The r-only Asavari is presented first and we set the ball rolling with a druta rendition by D.V. Paluskar. Both the old bandish and Paluskar’s elaboration sign up to a canonical Asavari: badhaiyya lavo.

Renditions of komal rishab Asavari abound. Several of the well-known conceptions appear to be seduced by Bilaskhani, leading to a violation of at least one standard Asavari clause, namely, the skipping of P in descent. Recall that r” n d M g is a vital Bilaskhani gesture. When introduced into the Asavari stream, quick measures are – or must be – implemented to stem any incipient Bilaskhani tide. One strategy is to first assert Asavari by, say, M P (n)d M P, before the slide down d M g, then reinstate Asavari through r M P, d M P. Although the specifics will vary, the reflective musician will signal his intent to stave off Bilaskhani and advance Asavari. Let us now examine the prevailing mores in light of this point and the various imperatives adopted.

An excerpt of alap by Rahimuddin and Fahimuddin Dagar reveals their cards. Later they pick up on a traditional dhrupad: aayo re jeet hi Raja Ramachandra.

Sawai Gandharva charms with delicate touches: preeta na keeje.

Following in his guru footsteps, Bhimsen Joshi.

Same lineage, similar mannerisms, a different bandish. Gangubai Hangal: mata Bhavani.

A vigorous Agra rendition by Younus Hussain Khan is somewhat tainted by his stepping once too often into Bilaskhani’s circle of influence.

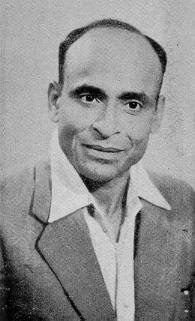

Gangubai Hangal

(© Rajan P. Parrikar)

Amir Khan‘s mehfil recording was first offered in the Todi feature under “Asavari Todi.” Komal Rishab Asavari and Asavari Todi are names of the same raga although some posit a distinction by prescribing an explicit Todi-anga for the latter. This masterly statement by one of the greatest musicians of all time shows Asavari at its most satvic.

Bade Ghulam Ali Khan sounds crisp and fresh in this 1950s mehfil recording.

Now, for the sole R-only Asavari exhibit, by the Gwalior duo of Akhtar Ali Khan and Zakir Ali Khan. It is a textbook Asavari mediated by the traditional Gwalior bandish, navariya jhanjari.

The third flavour of Asavari embraces both the rishabs. Typically, the higher shade prevails in arohi sancharis (S R M P d etc).

Faiyyaz Khan‘s stately alap makes it abundantly clear why the old bean was called “Aftab-e-Mausiqui.” Marvel at the swara lagav and his delicate meend work.

Allauddin Khan Maiharwale plays Asavari with both the rishabs as did his guru Vazir Khan (vide Bhatkhande). The proportion of r is calibrated, the Asavari lakshanas are beautifully cultivated and nourished.

Allauddin Khan’s boy, the nanga (naked) Emperor Ali Akbar Khan San Rafaelwale, surpassed him in performance. At his peak (pre-1970) Mr. Alubhai was without doubt the most complete instrumentalist of his generation. Ah, what a lovely Asavari!

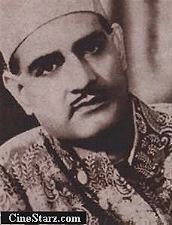

Allauddin Khan

Raga Jaunpuri

This raga is very close in spirit and substance to the R-only Asavari so much so that some musicians (for instance, Omkarnath Thakur) do not acknowledge any difference between the two. In recent times Jaunpuri’s dominance on the concert stage has virtually extinguished the shuddha rishab Asavari. A widely accepted point of departure in Jaunpuri concerns the komal nishad in arohi sancharis. Whereas in Asavari n is langhan alpatva (skipped) en route to the shadaj, that stipulation is relaxed in Jaunpuri. Still other minor areas of independence from Asavari are suggested, such as a higher weight for P over d. As in the shuddha rishab Asavari, R receives a pronounced grace of S. Whatever the case, Jaunpuri (and the ragas to follow) deeply embodies the Asavari-anga. A sample chalan is formulated:

P M P S” (n)d, P… PdnS”, d g” R” g” R” S” R” n d, P, d M P (M)g, (S)R S, (M)R M P n d, P

Madan Mohan‘s enduring composition from MADHOSH (1951) is among the myriad Jaunpuri-inspired melodies. It is delivered by that doyen of the maudlin brigade, the quivering palindromic lallu, Talat: meri yad mein tum na.

Jaunpuri is often rendered with a lightness of touch in contrast to the solemn Asavari. An energetic dhamar by Younus Hussain Khan spreads the spirit: marata pichakari.

The Atrauli-Jaipur musicians relish Jaunpuri and Kesarbai‘s is a superb performance: hun to jaiyyo.

The same bandish from her gharana confrère, Mallikarjun Mansur.

Kishori Amonkar‘s old masterpiece is well-known. Here we have her in an unpublished mehfil. The traditional vilambit, baje jhanana and the druta chestnut, chhom chhananana bichuva baje.

Roshanara Begum, a traditional khayal: so aba ranga ghuliya.

Faiyyaz Khan imparts deft graces to a well-worn Jaunpuri staple: phulavana ki gendana.

Faiyyaz Khan

Kumar Gandharva‘s Jaunpuri marches to the beat of a different drum, as is to be expected from a man who was no liege to any existing style or ideology. The bandish, his own: ari yeri jagari.

Ramkrishnabuwa Vaze breezes through as only he could.

Bismillah‘s piece will evoke nostalgic memories of festive occasions back home.

The final two items in Jaunpuri are among the earliest recordings made in India.

First, Gauhar Jan‘s 1902 release of the famous bandish…

… and a 1905 tarana by Abdul Karim Khan.

Raga Gandhari

Although Gandhari is of ancient vintage there is no consensus regarding its contemporary swaroopa. The Gandhari in common currency takes in both rishabs, the shuddha in arohi and the komal in avarohi prayogas. This puts it in proximity of the bi-rishab Asavari discussed earlier. Then there’s the Gandhari that likes both dhaivats. And yet another one that could be mistaken for Jaunpuri. Precise raga bheda within a specific school must, therefore, be determined empirically by examining their complete suite of Asavariants.

The Gandhari of two rishabs purveyed by Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang” has Bhatkhande‘s sanction. The Chaturpandit, in turn, holds out the dhrupad taught to him by Vazir Khan – kahiyo Udho tuma – as the touchstone for this raga. The contours of Gandhari take after Asavari/Jaunpuri and the komal rishab typically enters the frame in conclusion of a melodic idea. For instance:

R M P d M P (M)g, (S)R M P n d P (M)g, (g)r (g)r S

Ramrang suggests that there is a increased presence of Todi here. Hence the raga also goes by Gandhari Todi. Both these compositions lay bare the raga.

S.N. Ratanjankar takes a similar view of Gandhari in two marvelous compositions one of which is a tarana rendered by K.G. Ginde.

Mushtaq Hussain Khan‘s version is for all intents and purposes a standard issue R-only Asavari. There was clearly more than one version circulating in Rampur-Sahaswan.

Mallikarjun Mansur

Gwalior, too, is ambivalent on the issue. There’s the bi-rishab Gandhari, recorded in this splendid performance of D.V. Paluskar: beerava manuva saguna bicharo.

And there’s this breakaway version with just one rishab (shuddha) and both dhaivats, as witness this rendition by Hameed Ali and Fateh Ali Khan.

Atrauli-Jaipur gets to have the last word. True to form, Alladiya Khan has conceived his Gandhari with a twist. There’s just one rishab (shuddha), the avaroha traces out a peculiar trajectory bypassing the pancham (R” n d M g R). The cameo role of the shuddha dhaivat is masterful and will be left to the reader to ferret out. Mallikarjun Mansur, kara mana tero.

Raga Devgandhar

The recipe for Devgandhar: take shuddha rishab Asavari, add shuddha gandhar as in R n’ S R G, M. Shake well (but don’t stir). This proviso of G adds a most beautiful touch to the proceedings if executed judiciously. The raga is popular with the Gwalior musicians. A sample chalan assumes the following form:

R M P n d P, d M P (M)g, (S)R S, R n S R G, M, P (M)g (S)R S

K. L. Saigal‘s very first recording in 1932 went on to become a national chant. He was initially paid 25 rupees for the song, and when the recording company later offered him much more in response to the massive sales, Saigal-sahab refused the largesse: jhulana jhula’o.

K.L. Saigal

From SARGAM (1950) comes this nugget conceived by C. Ramchandra. Lata Mangeshkar and Saraswati Rane: jab dil ko satave gham.

Ramrang‘s composition, samajhata nAhiN, formally introduces the raga.

S.N. Ratanjankar: first the traditional composition, raina ke jage, and then his own bandish, aaja suna’o.

C.R. Vyas: raina ke jage, and then the Gwalior favourite, ladili bana bana.

Ladili bana is reprised in vilambit Tilwada by Krishnarao Shankar Pandit.

The concluding piece by Jitendra Abhisheki is the much-loved cheez of “Manrang,” distinguished by its staccato design: barajori na karo re Kanhaie.

En passant: An extension of Devgandhar with an additional komal rishab has been developed by S.N. Ratanjankar and it goes by “Devgandhari Todi.”

Jitendra Abhisheki

Abdul Karim Khan‘s recording of chandrika hi janu mistakenly carries the “Devgandhar” label. It is the Carnatic Raga Devgandhari (not Devgandhar) that has swara contours closely allied to the song, a clue to the origin of the labeling error.

Raga Khat

Most vidwans are of the opinion that the word “Khat” is an apabhransha of “Shat” (meaning six in Sanskrit); the reference is to the six ragas said to constitute Raga Khat. However, even among those who work with this premise, there is no consensus on just what those six ragas are. Consequently, a wide variety of opinion is encountered concerning the swaroopa of this sankeerna raga. The curious reader is referred to Pandit Bhatkhande‘s detailed discussion of the several prevalent flavours of Khat. Here we shall take the empirical approach and briefly nibble at snapshots from available recordings.

Kesarbai Kerkar

Although Raga Khat does not lend itself to a generalized shastraic capture, a few observations usually hold up: most current versions take Asavari for their base and then co-opt material from other ragas. The andolita nature of komal dhaivat stands out as a defining characteristic. None of the versions finds use for the teevra madhyam. The adjunct ragas are drawn from a pool with members as varied as, but not limited to, Bhairavi, Desi, Sarang, Suha Kanada, Sughrai and Khamaj. With its inscrutable twists and turns, Raga Khat has traditionally shown a bias for dhrupad-oriented treatment. The sadra in Jhaptala, vidyadhara guniyana son, has been the vehicle of choice for a number of performers as seen in the next four expositions.

The andolita nature of d and the recurring n P sangati find expression in K.G. Ginde‘s excerpt. Also take measure of the avarohi D in the astha’i and the arohi M P D n S” prayoga in the antara.

Vazebuwa‘s treatment of the andolita komal dhaivat occasions delight.

Ramkrishnabuwa Vaze

The influence of Raga Desi in the poorvanga is conspicuous in the Atrauli-Jaipur panorama flashed by Kesarbai Kerkar.

Mallikarjun Mansur injects an occasional P D n S” sangati in the antara (for instance at around 3:29 into the clip).

The final item in the Khat parade markedly deviates from its predecessors. Whereas the earlier flavours all employed shuddha rishab, Bade Ghulam Ali Khan builds on matériel furnished by Komal Rishab Asavari.

Bade Ghulam Ali Khan

Raga Shobhavari and Audav Asavari

The audav-jati (pentatonic) scale – S R M P d – has been developed into a raga. The absence of gandhar inhibits the full realization of the Asavari anga. We have two instances on offer.

Mohammad Hussain Sarahang of Afghanistan sings it as Raga Shobhavari: Prabhu karatara.

Another approach is taken by Amarnath, a pupil of Amir Khan, who files it under the Audav Asavari label. After listening to his rendition a friend perceptively observed that he aspires for the heights of an Amir Khan but ends up being waylaid by Banditji.

Other variants of Asavari, mainly hybrids such as Jogiya-Asavari, Sindhura-Asavari etc., are also heard in the lighter genres. They are not considered ‘big’ ragas.

Acknowledgements

Very many thanks to Romesh Aeri, Ashok Ambardar and Ajay Nerurkar for fulfilling some of my requests for published and unpublished recordings. Anita Thakur of the (now-defunct) SAWF website supplies the kindness, energy, and cheer to keep this effort going.