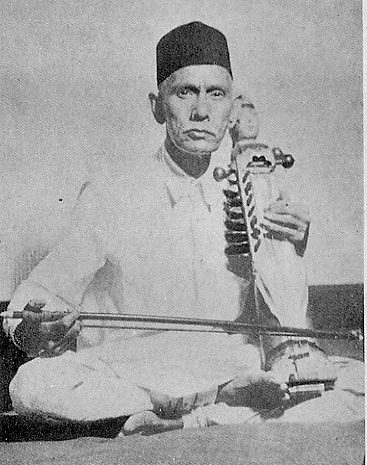

Bundu Khan

(1880-1955)

About Bundu Khan

From: Here’s Someone I’d Like You To Meet by Sheila Dhar

Playing for the Flowers – Excerpts

I don’t know exactly when my family adopted Ustad Bundu Khan as their favourite outsider. He had always been there as far back as I can remember, lending colour, variety and a little bit of magic to our lives, specially on occasions like the Holi festival, a wedding in the family, or even a dinner party my father sometimes threw for the cultural elite of Delhi. A sarangi recital by Ustad Bundu Khan usually preceded or followed the eating and drinking and was regarded as a great treat offered by our family. Not many of the invitees had specially cultivated ears but the general view was that classical music was a good thing and should be sought after. The charm of the music was greatly enhanced by my father’s fabulous introductions. He tended to romanticize and mystify the greatness of the artiste, his instrument, the raga, and the treasure-house of Hindustani music in general.

…Bundu Khan’s occasional visits gradually became a regular weekly feature. He came every Sunday when my father was home and spent the whole day playing and explaining ragas to whoever cared to listen, and even to those who did not. Most of the time my father was the core of his audience but, even when he was not, Bundu Khan’s enthusiasm for his art continued to overflow. He would play for whoever he sighted – a child, a servant, giggling teenagers or serious adults. And when there was no one, he happily and compulsively played for himself. He always carried his sarangi on his person as though it were a part of his body. It was said about him that though he was a renowned artiste who had been court musician of the princely states of Rampur and Indore, he would just as happily accompany a lowly wayside villager reciting couplets from the Ramayana of Tulsidas or play at the Ramlila celebrations in the Parade Grounds in front of the Red Fort…

One Sunday morning Bundu Khan got lost in our house. Dependable old Masoom Ali, my grandfather’s chauffeur, had driven the family Dodge to Suiwalan and brought the maestro back in accordance with my father’s standing instructions and deposited him on the veranda. After a few moments my father hurried out of his dressing room to greet him but he was nowhere to be seen. Not in the lavatory, not still in the car, not on the terrace, nowhere. My father’s faithful valet, the smirking Jai Singh whom we all hated, was sent hunting every where without result. Half an hour after the panic set in we heard the faint, scratchy sounds of a sarangi. They seemed to be coming from the garden but we could not see anyone there. We followed my father in the direction of the sound and tracked it down to a tall, thick hedge of sweetpeas that divided the huge garden in front of our house into two sections. Ustad Bundu Khan was lying in the flower bed on the farther side, his instrument balanced on his chest and shoulder, his eyes closed, completely engrossed in the music he was playing. Even my father who prided himself on courtly manners did not know how to awaken such a great musician from his reverie or how to call out such a revered name aloud. Anyhow, with much fake coughing and embarrassed clearing of the throat my father managed to catch his attention. Ustad Bundu Khan opened his eyes, just a slit, and scrambled to his feet when he saw the concern on the faces of the small assemblage.

‘It is spring time, and I was playing for the flowers’, he said in complete explanation. …My mother poured a cup of tea for the Ustad and handed it to me encouragingly. Her manner told me that she had absolute confidence in my ability to offer it to our eminent guest in a proper way. Ustad Bundu Khan took the cup from me with a vague smile as though it were a bird that might fly away. I brought the sugar bowl next and asked him how many spoons he wanted. He looked mystified and said in his soft, hoarse voice, ‘As many as you feel like putting in, it doesn’t matter’. I started to add sugar to his cup, hoping he would stop me at some point; but when he didn’t, even after I had put in six teaspoons, I put the bowl down myself. From the platter of hot samosas my mother prompted me to offer next, he picked up two and thrust them into the teacup, stirring the whole mess vigorously with a teaspoon, looking into the middle distance with faintly rheumy eyes…. All the other members of the family present at the tea were gazing adoringly at him as though he had just provided yet another proof of his other- worldliness.

…Once in a rare mood he began to talk about the rigorous training he received in his youth from his maternal uncle Mamman Khan. The incident he described was not aimed at anyone. Perhaps he just enjoyed recalling it himself.

‘I had practised fast runs in the raga Bahar for three years. Both the ascent and the descent of the raga are looped, so it is not easy to be fluent at speed. But I was determined to earn a word of praise from Mamu. I worked hard at a typical taan of the raga until it was perfect and then I confidently played it for him. He made a face and shook his head. It was not supple enough, he said. According to him, my taan in the descent was like the neck of a pig which is so thick that it cannot even look back. I went to work for another year, for several hours a day, just concentrating on the problem of the pig’s neck. Finally, I managed to get it right. You see, the taan does not actually need to look back over its shoulder, but to be beautiful it must sound as though it could bend if it had to.’

‘So, what did your Mamu say when you got it right?’, my brother asked eagerly.

Ustad Bundu Khan smiled shyly, looking like a grizzled elf. ‘Mamu heard me go up and down many times. Then he said “Yes”.’

…Once a music circle in Allahabad invited him to perform and offered a thousand rupees as his fee in addition to travel and living expenses. He brought the original letter and the reply he had dictated to his son Umrao Khan for my father’s approval. The reply said in polite Urdu, ‘Unless I am paid at least five hundred and Umrao Khan is paid at least two hundred, I must refuse’. It took quite a lot of effort for my father to explain that the offer he had received was better than what he was asking for and that his son had not been mentioned at all in the invitation. Bundu Khan looked bemused, tried to count and add on the fingers of his hands but gave up after a while, his lined, childlike face wreathed in smiles.

…The Partition of the country in 1947 was a terrible trauma for the Ustad who did not understand at all what had happened and why. He did not want to go anywhere, or change his life in any way. He must have been about sixty years old at this time but no one knew his age for certain. Soon after Partition, many members of his joint family went away to Pakistan, including his brothers, sisters and son. He couldn’t bring himself to go, to leave the courtyard in his old family house where he had practised, played and taught for almost fifty years. So he clung to his old life for almost three years depending for emotional support on the depleted household of cousins and nephews who had stayed behind. But we could all see the change in him. He would just come in and sit down quietly with his eyes closed as though he were dozing, instead of playing as he used to. When invited to do so, he would get into the music and drown in it completely, but this did not happen automatically as before. One day my father asked him what was bothering him, and his eyes filled with tears.

‘I have tried’, he said, choking a little, ‘but it is difficult. My children have gone. My wife has gone too’.

After much agonizing, he decided to uproot himself and follow his family. My father devotedly undertook to make all the arrangements for his safe travel and went to enormous trouble to ensure that he didn’t have to worry about anything. I remember that he was very attached to an old radio set he had and wanted to take it, along with his large collection of sarangis. To arrange this was quite complicated at the time but with the help of friends in various offices and the army, my father managed to transport him quite painlessly and safely.

We never knew how he coped with his new life in Karachi. My father received only one extraordinary letter of thanks three months after his departure. He had dictated it to someone in Urdu and signed his name in his shaky, illiterate scrawl. The letter carried two sentences, the first said that he would never forget all that my father had done for him. The second was somewhat longer and said ‘Here are the important taans of Malkaus’. About twenty note-patterns in the raga Malkaus followed. My father was so touched that he wept. He said he would never need to use the Malkaus taans in his life, but Ustad Bundu Khan’s intention was to offer him what he considered most precious. This letter of Bundu Khan’s reverberated through the remaining years of my father’s life…

*****

B.R. Deodhar on Bundu Khan (from Pillars of Hindustani Music)-

…The Maharaja of Indore took sympathetic interest in Pandit Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande and his research work. In fact, he issued an edict to all court musicians to help Panditji in his work because of which it became obligatory on all musicians to call on Panditji whenever he was in Indore. Khansaheb Bundu Khan, being naturally inquisitive in musical matters, needed no persuasion to visit Panditji from whom he derived light on the theoretical aspects of music. He had great respect for Panditji’s way of thinking, his analytical approach to ragas and the concept of thaat (raga divisions). Panditji used to tell me that Bundu Khan had given him a great deal of help in preparing textbook compositions (describing the special characteristics) pertaining to various ragas. Bundu Khan benefited greatly by his excursions in the field of theory of music. He thereby acquired a new insight because of which he could eloquently explain to others the precise nature of each raga he played. Because of his grasp of theoretical matters, whatever he said was logical and analytically sound…

…Apart from regular riyaz on sarangi the day was spent in contemplation of cheejs along with a modicum of writing. He was completely unaware of political upheavals or events. I heard an interesting anecdote about this. During the days of partition when the talk of a separate Pakistan filled the air, a number of Muslim employees of All India Radio (e.g., sarangi and tabala players) were discussing these matters. Barrister Jinnah was about to visit Delhi and the Delhi Muslims were preparing to give him a grand reception. Khansaheb happened to visit the Delhi Radio Station for his broadcast. He was as usual playing something on the sarangi when he overheard someone saying, “Jinnah saheb is also expected to visit the Radio Station.” Khansaheb promptly said, “Who is this new Jinnah Khansaheb? I thought I knew all Indian singers by name, but until today, I had not heard this singer’s name. Let me know when he is expected at the Radio Station. I shall accompany him (on the sarangi).” Obviously, Khansaheb was ignorant of epoch-making political events – he did not know whether Jinnah was going to visit the radio station for a music broadcast or for making a speech…

…Khansaheb rarely lost his temper. But, on the rare occasions, when he did, he found great difficulty in regaining control. There was little love lost between him and Umrao Khan, son of Khansaheb Tandraj Khan. There had been occasions when each had used invectives against the other. His Delhi friends once told me that Khansaheb had found a novel way of wreaking vengeance on his adversary. Having discovered that his first-born was a male he named him Umrao Khan. Later, whenever his sworn enemy did anything to displease him, he would vociferously shout recriminations at his rival’s ‘substitute’, viz., his son Umrao Khan. It helped to assuage his anger…

…Khansaheb loved his son dearly and spoilt him. He did not deny him anything – provided the child by his bawling and tantrums did not disturb his sarangi playing. Khansaheb’s son too was eccentric like him. He was fond of riding pick-a-back on his father and poor Khansaheb was often seen strolling in the bazaar in this manner… …Bombay audiences are not unfamiliar with Khansahib’s sarangi playing. During recitals he played difficult ragas but rarely. He had a preference for complete (ragas with straightforward ascending and descending scales). During riyaz too, he used to concentrate mainly on such ragas. In moving up or down he would use spirals of notes and build up the ascending or descending scales into a sort of circular movement. Having presented the two scales in a straightforward manner a couple of times, he would proceed to drop each note by turns and then interchange the notes. But since everything he played was rhythmically perfect, it held the listener spellbound. Having decided the kind of technique he wanted to employ, he was scrupulous about presenting all the combinations that followed. He did not ignore alapi and jodkam.

When Khansaheb was in an expansive mood he was completely unassuming and status meant nothing to him. He would accompany even a child on the sarangi and make the recital interesting. But God save the arrogant person who wanted to show off while Khansaheb accompanied him on the sarangi! It was not in his nature to provoke anyone but let someone provoke him and he would invariably accept the challenge. On one occasion, a celebrated singer who considered himself a notch above everyone else gave a recital. Khansaheb provided the sarangi accompaniment. The vocalist started off on a series of spirally ascending tanas. But halfway through a tana when he found that he was short of breath, he would terminate the passage abruptly and halt on the sam. But Khansaheb, refusing to acknowledge the halt, would proceed to complete not only the palta (note combination) in question, but the remaining passages in the series, systematically, and after a couple of rhythmic cycles arrive at the sam in a grand finale. Then he would turn to the singer and say, “This is where the passage ends.”

Khansaheb published a twenty-page Hindi book Sangeet Vivek Darpan in 1934. In this book he confines himself to two ragas Bhairavi and Malkauns and mentions the names of the different varieties of tanas I have referred to earlier. He wanted to commit to writing whatever he knew about music, his store of cheejs and varieties of tanas etc. He even showed me the Urdu manuscript of this book. Unfortunately the book was never published for want of funds and high printing costs. I think if some wealthy patron financed its publication the book would certainly make a very useful addition to the available literature on music. During the partition riots, Khansaheb sent the rest of his family to Lahore but himself continued to stay in Delhi. After a few months he went to Lahore to bring his family back to Delhi. Some of his friends and admirers there persuaded him to accompany them to Hyderabad (Sind). He was about to start for India when he found his way barred by the newly imposed restrictions against entry of Pakistan nationals into India. The All India Radio people tried their level best to obtain a special immigration permit for him and his family but they did not succeed. Khansaheb died in Pakistan on January 13, 1955 at the age of seventy-five. His death created a void which could not be filled.