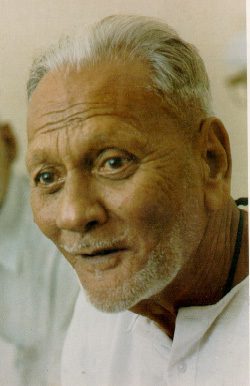

Bismillah Khan

(1916-2006)

♫ Bismillah Khan in conversation with Uma Sharma

About Bismillah Khan

From: G.N. Joshi’s 1984 book Down Melody Lane

Ustad Bismillah Khan The shehnai is perhaps the most popular of all the instruments in Indian music, because it sounds extremely sweet. It is an ancient wind instrument played all over India. It is played morning and evening at the time of prayer in most big temples, during holy festivals, and on all auspicious occasions. The sound of a shehnai at once fills the atmosphere with a soothing sweetness and sublime peace. This small instrument, hardly two feet long, produces magic notes that hypnotize listeners.

Bismillah Khan, the most outstanding and world-famous shehnai player, has attained astonishing mastery over the instrument. He was born in a small village in Bihar about 60 years ago. He spent his childhood in the holy city of Varanasi, on the banks of the Ganga, where his uncle was the official shehnai player in the famous Visvanath temple. It was due to this that Bismillah became interested in playing the Shehnai. At an early age, he familiarized himself with various forms of the music of UP, such as Thumri, Chaiti, Kajri, Sawani etc. Later he studied Khayal music and mastered a large number of ragas.

I met and heard Bismillah for the first time in 1941, when he came to our studio for a recording. At that time his elder brother also played with him. Both the brothers were expert players, but the famous Urdu saying “Bade bhai so bade bhai, lekin chhote bhai – Subhanallah!” perfectly described the brothers. When they played together Bismillah Khan always played down his own part as he did not wish to overshadow his brother. ‘Even though I have the ability, I must always remember that he is my elder brother’ he always said with humility and modesty. I ventured to question him about this after the death of his elder brother. He said again, ‘He was my elder brother, hence it was not proper for me to play better than him’.

Bismillah Khan’s party included three or four accompanists, one of whom gave him the main complementary support. Instead of a tabla, a duggi player provided rhythm accompaniment. Nowadays, Bismillah Khan has a tabla also. The duggi consists of two drums, like a tabla and dugga, but smaller in size. The duggi has neither the resounding quality of the tabla nor the peculiarity that the tabla has of sustaining the frequencies of a note (aas) but since it is the traditional instrument in UP, Bismillah Khan prefers to have it.

Ever since Ali Akbar Khan and Ravi Shankar introduced Indian music to the West, a number of Indian musicians have been invited to perform abroad. It was therefore hardly surprising that a musician of Bismillah Khan’s calibre should be one of them. In 1964, when I visited London and Europe, I found that many music lovers in UK, France, Germany and other countries had already come under the spell of Bismillah’s LP records. On my return I repeatedly urged Bismillah Khan to accept invitations from those countries. But he was mortally afraid of air travel and hence avoided going abroad. When in 1965, he received an invitation to play in Europe, he made impossible demands just to get out of it. The LP records which we used to release every three or four months further increased the interest of western listeners. In 1966 he again received through the Indian government a flattering invitation from the UK to participate in the famous Edinburgh festival. He resorted to his old tactic of making impossible demands such as, ‘I won’t go by plane, I want 10 people to accompany me and I want so much remuneration besides…’,etc etc. This was done in the hope that the invitation would be withdrawn. But he was pressurized into accepting the invitation by a very senior official in the Indian government who offered him fresh inducements. Bismillah Khan agreed to go to Edinburgh, but on one condition. He demanded that he and his staff should be first taken, at state expense, on a pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina. This wish was granted and, at last, Bismillah Khan boarded a plane. He completed the Haj pilgrimage at state expense and, fortified by prayers and blessings received from Allah, reached England safely. Bismillah Khan was the star attraction at the Edinburgh festival that year. His shehnai, sometimes soft and sweet, sometimes vibrantly alive with sonorously rich alapi, filled the air and brought the vast audience under its magic spell. The next day the papers were full of lavish praise for his divine performance. The following year, he received an invitation from the USA. Having realised how comfortable it is to travel by air, he did not raise any objections. He toured all over America regaling millions of people. He has since become a veteran air traveller and is always willing to visit any country of the world.

The Government of India bestowed on him the title “Padmashri”; later he was further honoured by the title “Padmabhusan”, and now the “Padmavibhusan” has been conferred on him. Inspite of being glorified in this manner he remained as modest as ever. When invited for a recording he always came without demur. He once had a program at seven in the evening, and had a reservation on a early morning train the next day. At my request he came to our studio at about midnight, after the concert. By early dawn had recorded material sufficient for two records. After having breakfast in our studio he went straight to the station to catch the train.

I was always trying to find new ways to increase the sales of our records. When the jugalbandi record of Ravi Shankar’s sitar and Ali Akbar’s sarod proved to be a hit, I decided to record a jugalbandi of the shehnai with some other instrument. A jugalbandi of the shehnai and the sitar was used in the film ‘Gunj Uthi Shehnai’ and it was a great success. It had been played by Bismillah Khan and Sitar Nawaz Abdul Halim Jaffar Khan. When I put my idea to Halim Jaffar he said to me candidly, ‘It won’t work. The jugalbandi in the film fit in the situation in the picture’. Also the jugalbandi in the film lasted for only three minutes. An LP record, 20 minutes long, would not according to him, be able to hold the interest of the listeners. The sitar sounds very soft and gentle compared to the vibrant and powerful notes of the shehnai. The volume of a sitar can be electrically magnified only upto a certain limit. Any further increase will result in distortion (This is true of all musical instruments). I therefore gave up the idea for the time being. But when Bismillah Khan went abroad to perform in the Edinburgh festival where Ustad Vilayat Khan also was giving a sitar recital, I grabbed the opportunity. Through our London office we were successful in bringing an LP with these two star artists on the shehnai and the sitar.

After this successful experiment, the idea of making another of the shehnai and some other instrument gripped me. The famous violinist Pandit V.G. Jog was at that time a producer at AIR Bombay. I made this proposal to him. Jog immediately favoured the idea and in a few days a joint programme of shehnai and the violin sponsored by All India Radio was held before a select audience. The programme, in my opinion, was not a success and was not at all what I had expected it to be. However, I still felt that it could be done well and came up with an idea which I discussed with my friend Pandit Jog. I suggested that the two instruments having similar tonal qualities would sound well together if they were played in different octaves. When, for instance, Bismillah Khan played in the Taar Saptak, Pandit Jog could play in the Mandra and Madhya saptak, and when Khansaheb was in the lower saptak, Pandit Jog could play in the Taar saptak. There would thus be a striking contrast in tone, pitch and timbre. The artistry of both the veteran players would be emphasized and there would be a perfect blending of the two instruments. When we did this and issued the record, true to my expectation, it was a thundering success.

During my 7-month trip around the world, no fresh record of Bismillah Khan was made. As soon as I resumed duty after my return in March 1971, I decided to record two fast selling artists who had not been available during my absence. They were Bismillah Khan and Bhimsen Joshi. The annual music festival of Sur Singar Samshad usually takes place in Bombay in April every year and it is usually inaugurated by Bismillah Khan. I therefore sent him a telegram and a letter asking him to spare time for a recording during his visit to the city.

As a member of the governing body of the Sur Singar Samshad I attended a meeting at the residence of its director Mr. Brijnarayan. Bismillah Khan also dropped in at the time of the meeting which was held on a Thursday. The sammelan was to open on Saturday and we therefore agreed to have a recording session the previous morning, that is, Friday is the Muslim day of prayer, and devout Muslims take particular care not to miss their noon prayer. Khan Saheb therefore agreed to do the recording from 8.30 in the morning so that he would be able to attend the Jumma after the recording. Accordingly I came to the studio at 8.30 on the dot. I was followed almost immediately by Bismillah Khan’s accompanists. Soon afterwards Khan Saheb came up in the lift. I went to greet him and was surprised to see him in dark glasses and all the more perplexed to see him wearing them so early in the morning. Bismillah gave an explanation. Bombay at that time was in the grip of a particularly infectious eye epidemic – conjuntivitis – and Khan Saheb had fallen victim to it.

He said to me, ‘I couldn’t sleep at all last night and I’m feeling very miserable’. I said, ‘You shouldn’t have bothered to come then’. ‘Oh no! I couldn’t do that,’ he said, smiling. ‘I gave you my word that I would come at 8.30. I didn’t want you to say that I don’t keep my promises’. I was touched to the core. A true artist is always careful to preserve good relations with his friends. Khan Saheb really looked as if he was in great pain. Seeing him thus I said, ‘We will cancel the recording’. ‘No no’, he said. ‘Since I am here now we shall see what we can do’. He took his seat on the platform and in two hours he recorded two ragas and a thumri for an LP. I was standing right in front of him. He was holding the shehnai to his lips and was completely engrossed in the haunting music that poured out from the tiny instrument. He played on, completely oblivious of his discomfort and his streaming eyes. He finished the magnificent recording and asked me if I wanted more!

What I miss most after my retirement from HMV is the pleasure I used to get from Bismillah Khan’s shehnai. I am sure that by God’s grace, he will continue to delight millions in our country and abroad for many years to come.