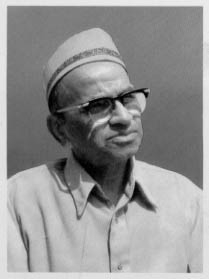

Basavraj Rajguru

(1917-1991)

About Basavraj Rajguru

From cnsnews!parrikar Mon Aug 5 09:11:16 MDT 1996 Article: 19498 of rec.music.indian.classical

From: parrikar@spot.Colorado.EDU (Rajan P. Parrikar)

Newsgroups: rec.music.indian.classical

Subject: Great Masters 26: Pandit Basavraj Rajguru Date: 5 Aug 1996 06:05:58 GMT

Organization: University of Colorado, Boulder Lines: 284

Namashkar.

The Dharwad district of northern Karnataka boasts a formidable tradition in Hindustani music and adduces the following redoubtable list in support of its claim: Bhimsen Joshi, Gangubai Hangal, Mallikarjun Mansur, Kumar Gandharva and Basavraj Rajguru. All exceptional, apratim performers. Today’s Great Masters 26 dwells on the last-named in the list, the late Pandit Basavraj Rajguru.

Pandit Basavraj Rajguru belonged to the now-extinct breed of musicians who earned their musical escutcheon by hitting the rough itinerant road, traversing the length and breadth of Bharat in indefatigable pursuit of the good and beautiful, and in the process fashioning their musical perspectives in marvellous and exquisite detail. A performing artist of a very superior calibre, Rajguru was also a highly learned man whose understanding of the Veerashaiva tradition and its literature and poetry was peerless. Likewise, his mind was home to an enormous amount of compositions of Purandaradasa and other Carnatic composers.

His personal relations with people were characterised by a simple candour refreshingly devoid of malice, pretension and hypocrisy. He was known for his extremely frank manner of opinion and he didn’t suffer fools gladly, often employing his sharp wit and also downright discourtesy to bring to ground pompous cocks-of-the-walk. Such a disposition didn’t endear him to the musical or political “establishment” in the country and he was, for the most part, sidelined. But Basavraj didn’t mind. He was content leading the quiet life in his native Dharwad and made teaching his prime focus and mission during the latter half of his life.

In the following account, Nachiketa Yakkundi (Sharma), his young and gifted shishya who lives in the Bay Area, writes lovingly about his guru, offering this piece as part of his guru- dakhshina on the occasion of the recently concluded Guru Poornima.

Regards,

Rajan Parrikar

*****

Pandit Basavraj Rajguru

by Nachiketa Yakkundi (Sharma)

Blessed is Yeliwal, a quaint village in the north Karnataka district of Dharwad, for it is the birthplace of one of the greatest exponents of Indian music, Pandit Basavraj Mahantaswamy Rajguru. Born on 24 August 1917 in a family of scholars, astrologers and musicians, Basavraj was initiated into classical music at the age of seven by his father, who was himself a renowned Karnatic musician trained in Tanjavur.

Basavraj was fond of nATyagIt from a very young age. He landed himself in trouble one time too many for playing pranks trying to persuade drama producers and actors to let him sing in their plays. Recognizing Basavraj’s obvious talent and zeal for the stage, his father had him inducted into Vamanrao Master’s travelling drama company, where Basavraj tasted his first morsel of fame. At the age of 13 Basavraj lost his father. His uncle, fearing for his aimless future in the drama world, put the young Basavraj in the Samskrta PAThashAlA at the MUrsAvira MaTh in Hubli. Soon thereafter, in a rare twist of fate the blind Ganayogi Panchakshari Gawai discovered Basavraj and with little convincing from the MaTh’s swamiji, took the lad into his tutelage. It’s from then on that Basavraj’s music embraced a whole new beginning.

At the Shivayogamandir where Panchakshari Gawai bestowed the wealth of his immense knowledge upon Basavraj and other students who were not privileged enough to even pay gurudakshina to their guru, Basavraj mastered several rAgas and styles. He also became adept in such arts as wrestling, swimming and cooking. The Gawai, Pt. Rajguru would reminisce, had a style of teaching unlike anybody else. He would drill into his students the basics for hours together and would personally make sure each of his students practised for at least 12-15 hours a day. If he had to scold or strike anyone, he would make the student position his face accordingly and then he would slap him. Panchakshari Gawai was a very affectionate man, and had a soft corner for Basavraj, his most prized pupil. When Basavraj expressed his sadness because of his inability to pay gurudakshina to his guru, Panchakshari Gawai replied, “your gurudakshina to me will be the passing on of what you have acquired here to your own disciples.” In 1936 at the six hundredth anniversary celebration of the founding of the Vijayanagar empire in Hampi, Basavraj gave his first concert, accompanied by the Gawai himself on the tabla. Fifteen thousand people listened in awestruck silence to the young lad render a sonorous Bageshri and a Nijaguna Shivayogi vachana. The maestro’s career had commenced.

Basavraj recorded several rAgas for AIR Bombay and HMV between 1936 and 1943. Chief among the classics are the stupendous “BalmA na jA ghar soutan ke” in Hamsa Kalyan, the awe-inspiring “Sagari umariyA mori” in Brindavani Sarang, the fiery “Anahata NAda” in Shankara and several Basaveshwara vachanas, including “Parachinte emage eke ayya” and “Madakeya mADuvare maNNe modalu”. Listening to these still evokes a horripilated hair or two.

After the untimely demise of Panchakshari Gawai in 1944, Basavraj came to Bombay where he had the good fortune to learn from Sawai Gandharva. When the Sawai was struck with paralysis because of which he had to leave Bombay, he summoned Sureshbabu Mane and said, “Take good care of Basavraj.” Basavraj once again had the good fortune to learn under yet another stalwart. His thirst for knowledge then took him north-west into present-day Pakistan, where he came under the pedagogy of the Kirana gharana master, Ustad Waheed Khan, guru of Panchakshari Gawai. Basavraj then headed towards Karachi where he learned from Ustad Latif Khan for about six months. Basavraj’s brash, bold and confident personality had already created waves all around him. He would take up challenges from renowned performers, and effortlessly put their egos to rest.

On one such occasion, he was challenged to sing after Ustad Nishad Khan, who had finished rendering Purya. Basavraj confidently went up on stage and announced, “Ap dekhte rahiye, hum Nishad Khan ko Shadaj Khan banAdenge!” What followed was a Sohni that was so definitively supreme that the Ustad had no choice but to accept defeat. On another occasion where there was a bout of rivalry between Hindu and Muslim musicians, Chhote Ghulam sang a Todi so well that nobody dared follow him. But then, there was the young Basavraj. Upon the slightest coaxing by Pt. Nivrittibuwa Sarnaik and Pt. Vinayakrao Patwardhan, he sang Jaunpuri and immediately won the hearts of all the listeners present.

The dreaded time had arrived – 1947 – the partition of India and Pakistan. Hindus were being hunted down and beaten to death. Following the advice of Ustad Latif Khan, Basavraj hastily boarded a train that was carrying thousands of Hindus across the border. As luck would have it, the train was stopped near the border and most of its passengers brutally massacred. In a desperate effort to cling to dear life, Basavraj managed to escape unscathed and clung to the bottom of a railway bogey all the way from the border to Delhi. Basavraj then moved to Pune where he rented a room and performed on an average of two to three concerts a day. Just as his musical prowess was taking root in Pune, another disaster befell. Gandhiji was assassinated. What followed his assassination was a city-wide rampage on Brahmins, who were being singled out and killed because Gandhiji’s assassin, Nathuram Godse was a Brahmin. Since Basavraj was renting from a Brahmin, his life came very close to an end. Luckily for him, he was a Lingayat. When the killers confronted him, he showed them his Shivalinga and managed to escape unhurt. Having had enough of lucky breaks on his life, Basavraj left Pune bag and baggage. He returned to Dharwad and settled down.

His fame had spread far and wide and continued to spread; invitations for concerts came from every corner of the country. His repertoire included a kaleidoscope of styles, from the pure classical khayAl and dhrupad/dhamAr to vachanas, nATyagIt, Thumri, and ghazal spanning eight languages. His collection of bandish’es was truly remarkable. (He would tell me that he knew at least forty to forty-five cheez’s in each rAga, and would sing them one after another right then and there. Alas! if only I had half the sense to record all of his wisdom…) Although wooing audiences wherever he went, Pt. Rajguru never however, failed to meet a challenge and squelch it. In 1955 at the Nagar Bhavan in Delhi, failing to see anybody follow Pt. Omkarnath Thakur’s magnificent recital, the organizers were ready to stage an instrumental piece, when Pt. Rajguru boldly announced, “Hum gayenge.” There are old timers who were present then who will still attest to having heard the finest Nayaki KanaDa ever rendered by any musician. In the same year, at the Nanded Sangeet Sammelan, Pt. Rajguru had the audience spellbound for almost twelve continuous hours (since Pt. D. V. Paluskar failed to show up), after which the then Information Minister, B. V. Keskar announced, “Arre, hamAre Rajguru to hukumi yekka hai!” Ace of trumps, indeed. Begum Akhtar, at another Rajguru concert, declared, “Rajguru yAne sUr kA bAdshAh.” The Government of India bestowed upon him the Padmashri in 1975 and the Padmabhushan in 1991. He also received several Sangeet Natak Academy awards from the central and state governments alike. Aside from being awarded prestigious titles by various organizations, he was also awarded an honorary doctorate by the Karnatak University, Dharwad.

When he wasn’t impressing and spellbinding audiences all over the country or being bestowed with lofty honors, Pt. Rajguru was busy refining yet another chapter in his life –

that of being a preceptor in Dharwad. He held his students very dear to himself. I have never seen or known of a teacher so accomplished, so talented, so great and yet so patient, so caring and so zealous about his students as Pt. Rajguru was. He never raised his voice or his hand at any student at any time. His way of correcting mistakes was through rigorous yet careful, unmitigated yet patient repetition of the correct way. There would be times when he would repeat a tAn for his students 15-20 times, and yet never tire. In the end he would not be satisfied if we got it right just once. He would not quit till we had the tAn perfectly executed at least three times in a row. He would sometimes not teach for days at a time and sometimes, four-five times a day, starting at five-thirty in the morning. Who, of his stature, would exhibit such patience and enthusiasm? The degree of tayAri and credibility of his students were his way of measuring how good a musician he was. He would always say, “Listen, no matter how big and great you are, if you cannot pass on what you have acquired to somebody else, your greatness is worthless. This is what my Guru, (Shri Panchakshari Gawai) used to say.” True to his guru’s words, Pt. Rajguru molded some of the finest gAyaks in India (Ganapati Bhat, Parameshwar Hegde, Shantaram Hegde, et. al.) and left behind more than forty disciples who are now dispersed all over the world.

The music world would be such a fabulous place if everybody followed the simple lifestyle that Pt. Rajguru followed. He was a strict vegetarian and had no vices. Ever. He had never even tasted tea in his life. He adhered to a strict regimen of pUja, sAdhanA, rigorous teaching, walking and a very voice-conscious diet. He never ate or drank anything fried, frozen, sour or fatty. The best part of travelling with him was lugging the 20+ pieces of luggage wherever we went with him, most of which consisted of food items! He was so conscious and careful about his voice that he would take all the ingredients for his meals, including boiled water, from Dharwad itself. Such was his dedication to Saraswati.

His layakAri was tremendously complicated at the same time that it was seemingly effortless. His tAns and boltAns spat fire at times and at times, carried the sea breeze. The sheer complexity in his style and the ease with which he used to render a complex rAga as though it were a written speech sharply defined his musical character. His ability to span three octaves would sometimes astound even himself. There were concerts where his key would be Safed-4 or Safed-5, so high that it would be almost impossible for his vocal accompanists to keep up with him! Harmonium, sArangi and tablA players who accompanied him would always have complete liberty to play and create as they wished, which is why so many of his accompanists to this day acknowledge their growth and merit to Pt. Rajguru’s encouragement and generous personality. Witnessing him on stage was an unparalleled spectacle. The pure energy, aura and charisma he exuded would throw the entire mehfil into a world filled with endless colors and emotions. The training he received from twelve gurus – his father, Panchakshari Gawai, Neelkanthbuwa Mirajkar, Sawai Gandharva, Sureshbabu Mane, Bashir Khan, Mubarak Ali, Waheed Khan, Latif Khan, Inayatullah Khan, Roshan Ali and Govindrao Tembe – in three gharanas – Kirana, Gwalior and Patiala – was intricately amalgamated as only Pt. Rajguru could have, to bear a stamp which could be aptly termed as nothing less than that of the Rajguru gharana.

Pt. Rajguru is known to have put to tune and popularized the great vachanas of great reformers and saints like Basaveshwara, Akkamahadevi, Nijaguna Shivayogi and others. Another great stalwart from Dharwad, Pt. Mallikarjun Mansur is known to have initiated this movement. Pt. Rajguru rendered MaraThi nATyagIts, Purandaradasa (and other saints’) padas and vachanas as if they flowed in his blood.

His dream of coming to the U.S. eluded him. After carefully planning a Fall 1991 concert tour in the U.S., I visited India that summer. I accompanied him and his wife to the Madras Consulate where he was given the performer’s visa. On his way back to Dharwad from Madras, he took ill in Bangalore, where he had a mild heart attack. Already a patient of diabetes and low blood-pressure, the three-pronged attack was fatal. All his might to survive was of no avail. I was fortunate enough to be at his side in moments when he breathed his last. A few hours before he died he said to me, although his consciousness was fuzzy and he had no inkling about what time of day it was, “Take the tambura from the corner and sing the Sa for me. It’s time for Bihag.”

Surely enough, the time was 11 P.M. After the Government of Karnataka under the then chief minister S. Bangarappa managed to utterly defame and degrade itself by expressly refusing to carry the dead body of my Guru from Bangalore to Dharwad, we rented a taxi in the wee hours of that fateful July 21 1991 morning and carried the dead body. In Dharwad our taxi was greeted with virtually the whole city lined up outside Rajguru Chawl. Pt. Mallikarjun Mansur paid his last respects to the departed Rajguru and declared, “Wah! Even in his death he looks like a king!” Fitting words indeed to a fitting king.