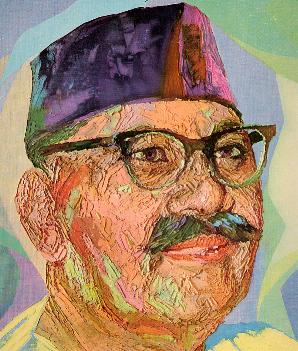

Bade Ghulam Ali Khan

(1903-1968)

♫ Bade Ghulam in conversation with Thakur Jaidev Singh

About Bade Ghulam Ali Khan

Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan by Susheela Mishra (from Great Masters of Hindustani Music)

The death of no other classical musician in recent times has had such a stunning effect as the passing away of Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan had in April 1968 on the world of Indian music. AIR was flooded with poignant tributes and homages from great musicians, musicologists and music- lovers from all over the country.

The great maestro used to say: “Music is to me more than my food. It is my only life and I cannot live without it. I would rather die with a song on my lips than live without music.” Years ago, he had to undergo a serious goitre operation after which he was advised complete vocal and physical rest by his surgeon-friend. Hardly 24 hours had elapsed when he burst into a taan covering 3 octaves! When his surgeon affectionately admonished him for it, his childlike reply was: “I had to see if my voice has been affected. Without it, what use is my life to me?”

When Bade Ghulam Ali was stricken with paralysis in 1961 his admirers all over the country felt deeply grieved not only for themselves, but even more for the great Ustad for whom life without music would be nothing better than the silence of the tomb. Those who had seen his utter helplessness after the stroke, had no hope of hearing his wonderful singing voice again. But after some time, excited rumours spread that he was going to stage a come-back, rumours that seemed too good to be true. But he proved how mind can truimph over the body. There he was on the stage- “frail in body, but exuberent in spirit, looking like a disabled lion – still majestic in his deportment, a twinkle in his eyes, and that impish smile on his lips”. Music circles took the lead in restoring his self- confidence. In his programme (relayed by AIR) after receiving the Presidential Award, he seemed to have set a challenge for himself by singing Khayals and Tarana (in Yaman) – just to reassure himself that his taans had at least not been “crippled” by the stroke.

Another of his “come-back” appearances was in the Fourth Music and Dance Festival (1967) sponsored by the Goverment of Maharashtra. He had to be brought on a chair and seated on the stage before the curtain went up. He was surrounded by his various accompanists and admirers on the stage; but he refused to start singing. Reason:- “You have switched off all the audience lights and I can see no one in the dark. How can I feel like singing unless I have a darshan of my dear listeners who have come from far and near in their affection for me?” A glimpse of the adoring crowds, and he broke into his inimitable Khayal in Rag Chchaya (“Jo kare Ram Kripa”) full of [The kHayAl in Chhayanat is actually “Sugreeva Rama Krupa” – RP] devotional fervour. For the true musician, there is only one God – by whichever name you address Him. The great artist that he was, Ghulam Ali was not interested in political and religious differences. He knew of only two categories of humanity – music-lovers and the uninterested ones. “I know only one thing – Music ! I am little interested in other things. I am just a humble devotee of God and Music.”

Ghulam Ali not only believed in the divine origin of music but also in the story that music came into his family when one of his Pathan ancestors (Fazl Peerdad Khan) migrated to Hindustan from Ghazni, became a Fakir, and worshipped the Goddess of music for years among the lonely mountain-tops of the north until one day she appeared before the music-mad devotee and blest him. “Music will run in your family from generation to generation”. Peerdada handed over his ilm to Miyan Irshad Ali Khan (great- grandfatber of Ghulam Ali) from whom it came to Id Mohammad Khan (Ghulam Ali’s grandfather), to father Ali Buksh, uncle Kale Khan, and on to Bade Ghulam Ali. Their Gharana was known as the Kasur Gharana.

Born in Lahore in 1901, Ghulam Ali’s musical gifts were evident at an incredibly early age. As an infant he once wailed in the same pitch in which his father and his famous uncle Kale Khan were singing! Reminiscing over his childhood, the Ustad once said: “I do not know at what age I began to master the 12 notes. This much I can say. At the age of 3 or 4 when I started talking, I had some idea of the 12 notes. I learnt sargam as a child learns his mother-tongue.”

Recognising the musical potentialities of the child, Ali Bux put him, at the age of seven, under the tutelage of Khan Sahib Kale Khan of Patiala for the next ten years. After the Khan Sahib’s death, Ghulam Ali continued his training under his own father. Both his uncle and father bad received good training from Khan Sahib Fateh Ali Khan, the court musician of Patiala. What fired him with a feeling of challenge was a small incident. When Kale Khan died, a certain musician made a caustic remark that “music was dead with Kale Khan.” This put young Ghulam Ali on his mettle. In his own words: “For the next five years, music became my sole passion. I practised hard day and night, even at the cost of sleep. All my joys and sorrows were centred on music.”

Ghulam Ali was gifted with all the attributes of a great musician: musical lineage, sound training and high artistic sensibility. “To me the purity of the note is the supreme thing”, he used to say. Ghulam Ali also had the privilege of receiving talim from Ashiq Ali (who belonged to the Gharana of Tanras Khan), and from the late Baba Sinde Khan. Some people detected shades of Ustad Wahid Khan’s charming style in his Khayal alap. Whether it was a Khayal with a courtly theme, a Thumri with wistfully romantic word- content, a playful Dadra or a soulful Bhajan, Ghulam Ali Khan could always put his heart and soul into the song. We have no dearth of great traditionalists and purists who can impress the intellect by their technical mastery. But what is music without a soul! Ghulam Ali’s music was “the best imaginable blend of appeal and technique.” Few could touch the listeners’ hearts as he could. No wonder, that no other classical vocalist earned such country-wide adulation as he did. Among his many contributions to Hindustani music, the outstanding one is that he opened the eyes and ears of contemporary musicians and music-lovers to the prime importance of voice culture and voice-modulation and the supreme value of emotion in music. “A voice is not just a ready-made gift from the gods. One has to earn it, polish it, and gain absolute command over it by Sangeet Sadhana” – he used to say.

A remarkable fact in Bade Ghulam Ali’s life was his transformation, in the early part of his life, from the role of a Sarangi player to that of a vocalist. This experience really enriched his taans and we admire him all the more for it, but somehow Ghulam Ali never liked to be reminded about that -early phase of his life!

The amazing pliability of his voice, his unpredictable swara-combinations, the incredible speed of his tans, and the ease with which he could sway his audiences by his emotional renderings – these were some of the qualities which became the envy and despair of many a rival.

As I sit and recall the numerous concerts of Bade Ghulam Ali that I had the good fortune to attend, I find that there was not a single rasa that he could not bring to life through his music. Such was the power of his music that be it summer or winter, if be chose to sing Basant and (or), Bahar, he could conjure up before the audience, the entire beauty, youthful exuberance, bursting buds, and blossoms, the poignancy of separation and the entire atmosphere of Spring. Suddenly he would wave the magic wand of his music, and when he started that peerless Desh of his “Kali Ghata ghir aye Sajani”, the audience could almost hear the rumbling of thunder (in the deep, growling mandra notes) see the flashes of lightning (in his sweeping taan), and share the beloved’s agony of separation (through the exquisite meends) and so on. In his Thumri “Naina more taras rahe” (in Jangla Bhairavi), he could bring out the entire longing of the eyes to behold the “Pardesi balam.” What passion cannot music raise and quell! He sang strictly within the traditional framework, but what varied emotions he could pour into his dignified and devotional Khayals (like “Mahadev Maheshivar”, or “Prabhu ranga bheeni”), sensuous thumris like “Yadpiya Ki aye”, or “Tirchh najariya ke Baan”), poignant Dadras (Saiya bolbolo) playful Horis, and soulful Bhajans. By his richly expressive style, he has silenced the detractors of classical music who argue that it is “dry and flat,” and therefore, sans appeal. This pained Ghulam Ali, who used to say – “This is because generally our musicians are more interested in technical virtuosity. But really, emotion is the very soul of our music which has the power to express the subtlest nuances of feeling”. He proved his point by his own style. “From the heart of the singer to the heart of the listener” was true in the case of his music. For the rare perfection and popularity that he brought to the Punjab ang Thumri, he has been rightly called “the King of light classical music”. He had cultivated a full and splendidly modulated voice that charmed listeners. It was a soothing, polished voice that could float effortlessly over the 3 octaves, in slow long glides (meends) or in faans of inimitable speed.

It is true that Ghulam Ali belonged to a long and illustrious musical lineage – the Patiala Gharana. But it was his genius that chiselled off all the harsh crudities and angularities of the once dry Patiala Gharana, and lent it such a rare polish and glow that today it has achieved countrywide popularity. Bade Ghulam Ali Khan has left behind not only hundreds of singers trying to emulate him, but also thousands and thousands of music- lovers who cherish his music. No other North Indian vocalist ever attracted such large audiences in the South as did Bade Ghulam Ali Khan.

Bade Ghulam Ali never tried to win the approbation of those classical purists who judge the excellence of a perfor mance by the length of delineation of each raga. His aim was to appeal to the hearts of the millions who heard him. He would say: “What is the use of stretching each raga for hours? There are bound to be repetitions.” He was one of those rare musicians who was an adept in matching his music to the mood and tastes of his audiences. Indeed, few classical musicians have equalled his shrewd knowledge of audience-psychology. He used to give brief renderings of ragas at big conferences because he rightly felt that too elaborate alaps and badhat might sound tedious to the uninitiated who form the bulk of big gatherings. However, he inevitably poured out his sweetest art at exclusive private soirees. It was at the great Vikram Samvat Conference in Bombay that Ghulam Ali shot up to dizzy heights of fame. It was an unforgettable occasion. All the shining jewels of Hindustani classical music like Aftab-E-Mausiqui Ustad Faiyaz Khan, Ustad Alladiya Khan, Kesarbai and all the rest of the brilliant galaxy were present.

Young Ghulam Ali’s performance made him the sensation of the day. Those who heard him on that occasion still rave about the Khayals in Pooriva, and Marva and the Thumris that he rendered then.

At his abode, wherever he used to stay, whether Bombay, Delhi, Calcutta or Hyderabad, he was surrounded by his admirers all the time, and the Swarmandal was always with him. Every few minutes he would break into song to illustrate a point he was making. A firm believer in the debt that classical music owes to folk music, he could, with amazing dexterity, demonstrate the simple folk tunes like a real villager, and then suddenly sing out its fully polished classical counterpart in a scintillating manner! No wonder his admirers were always crowding around him throughout his waking hours. An ample, corpulent figure with a handlebar moustache, his face would become lighted up with expression as he sang, and music enriched with unsurpassed melodiousness would flow out of this great maestro.

During the Ustad’s last stay in Bombay (prior to his departure for Hyderabad and his last fatal attack), my brother, a devout BGA fan, in the course of his Cochin-Bombay- Calcutta flight, had a few hours’ halt in Bombay, before taking a plane to Calcutta. It was 11 pm when he reached Bade Ghulam Ali Khan’s place. Yet, with joy, the Ustad showed his hospitality, not by serving tea and sweets but by something more precious. “Bring my swarmandal,” he said to his son Munawwar. “Let me sing awhile for my dear guest.” My brother was overwhelmed by the great artiste’s humility, affection, and his utter absorption in music. One of my brother’s most cherished. possessions today is an old autographed Swarmandal of the Ustad.

Bade Ghulam Ali was not only everyone’s favourite, but the favourite of many musicians. When the news of his death spread (April 1968), great contemporaries like Begum Akhtar, Siddheswari Devi, Bhimsen Joshi, Dilip Chandra Vedi and a host of others spoke out in their grief over the “irreparable loss”. Siddheswari Devi looked nostalgically at a group-photo in which she sat next to the great maestro after a grand music conference in 1936, and said in a tearful voice: “The like of Bade Ghulam Ali Khan will never come. There will not be another like him.”

Begum Akhtar who had known him since long, paid her tribute thus: “I have never seen such a rare combination of greatness and simplicity. When I first heard him, I felt that I was hearing real music for the first time. He was my honoured guest for several months in Calcutta. He used to sing all day long. In fact, music was his sole interest in life, In sorrow he would draw solace from music. In joy also he would burst into song. What a rare musician!”

Under his pen name, Sabrang, he has left numerous lilting compositions – khayals and thumris. Sabrang had only one passion in life – Music. Today the great singer has merged into Nadabrahma, eternal bliss through music. His favourite Bhajan ever was and will be: Hari Om Tatsat.

Who knows future generations may refer to him with awe and reverence as we do of Tansen. Luckily, AIR has treasured the recordings of many of his memorable recitals for us and for posterity.

*********

Part 2: Vignettes from the past

From: PILLARS OF HINDUSTANI MUSIC

by B.R. Deodhar (Popular Prakashan)

[On Khansaheb BADE GULAM ALI KHAN]:

I believe the year was 1945. Khansaheb and I were seated on Chowpatty sands, chatting. The sun was about to set and its last rays had fanned out and bathed the West in red. The picturesque scene above was reflected in the calm waters of the Arabian Sea. It was a habit with Khansaheb to go to Chowpatty regularly every day to see the beautiful sunset. As he sat transfixed by the scene before us Khansaheb turned to me and said, “Deodharsaheb, this is the precise hour to sing raga Marwa. I am amazed by the ingenuity of our ancestors! Consider their perceptive artistry in employing that particular rishabh (re, ‘D”) and dhaivat (Dha, ‘A’) as they did! The hour of sunset is a most fascinating time. Lovers who have been separated begin to wonder at this time how they are going to spend the night in loneliness. The same thing happens to people who do not have a roof over their heads. The day passes by itself-but the night? They start worrying about finding a shelter for the night. In the seven notes of Hindustani music the most important resting place is shadja (sa, ‘C’). But in Marwa the very note (sa) virtually vanishes and whenever we use it briefly we feel a sense of relief. I am of the opinion that the chief aim of Marwa is to portray this anxiety or uncertainty”.

…[Bade Gulam to Deodhar]: “When I happened to be seated on the bank of a river, or in a park, I see birds flying here and there. I see them darting and dancing around without a care in the world; they suddenly take to flight and having reached a certain height dive down to their resting places in some tree. I am fascinated by all this. I want to translate all their delightful movements into music and I try to do this by means of a suitable tana e.g. one which moves very fast from the Sa (tonic) to pancham (Pa, ‘G’) of the higher octave and then circles down like a bird in flight, to the middle Sa…”

…One day Khansaheb had a radio broadcast at 1 p.m. As I was working for the Bombay Radio Station at the time, I too had to be in attendance. After he had finished, Khansaheb said, “Wait for a while. I have sent for a taxi – we shall go together.” It was mid-july and the rain was coming down in torrents. Besides, I was hungry. But I did not have the heart to say ‘no’ to Khansaheb. The taxi came along and we got in. Water in any form made Khansaheb happy and heavy rains in particular were pure bliss for him. Some of the rain- water seeped into the taxi and began to drench us but Khansaheb seemed to be in high spirits. He said, “Come Deodharsaheb, let us go to the sea-shore; the sea would be something to be seen right now.” I protested, “For one, I am famished and besides my clothes are beginning to get wet. So let me go straight home.” However, by way of compromise I agreed to let the taxi driver take us via Marine Drive. We came to Marine Drive and Khansaheb asked the cabbie to stop his vehicle at a spot where there is a cement-concrete projection. The waves of the turbulent sea at this point were thirty to forty feet high. Khansaheb said, “Deodharsaheb, the time and this place are just right for doing riyaz. Listen.” And he began to sing. Whenever a particularly massive wave broke and water spouted up Khansaheb’s tana rose in synchronization and descended when water cascaded down. Water rose in a single massive column but split at the top and fell in broken slivers; so did Khansaheb’s tana in raga Miyan Malhar. Sometimes, if his ascending notes failed to keep pace with the surging water, he was angry with himself but tried again till it synchronized perfectly with the surging water. This went on for three quarters of an hour. I got so interested in the whole proceeding that hunger and thirst were forgotten. Finally Khansaheb’s son, who happened to be with us, said to his father, “Let us go now – it is two-thirty p.m. and we are both hungry.”…

…I remember another interesting incident. One evening, Khansaheb gave me a long lecture on the importance of celibacy, especially to singers. The following day, while on his way to Chowpatty, he came to the school and urged me to go with him. I said it would take me a few minutes to get ready. Khansaheb said he would wait for me by the roadside. When I came down, I saw an extraordinary sight. A lovely Punjabi girl – she must have been around eighteen years old – was going towards Chowpatty. Our school is practically at one end of Chowpatty, and Khansaheb seemed to be a few steps behind and following her. The girl caught the attention of every passerby because of her beauty and the grace of her movements. I caught up with Khansaheb, tapped him on the shoulder and said, “Khansaheb, were you not yourself holding forth on the virtues of celibacy yesterday? But a passing lass seems to have turned your head today!” Khansaheb said, “You will hardly understand what I am thinking or looking for. Look what a beautiful piece of creation that girl is! And how intelligent the Creator must be to produce such captivating figure! She has turned the eyes of every passer-by to herself and she is completely unaware of this. Watch her graceful gait – the beautiful movement of her arms and neck! Come, I shall sing to you what I have just seen.” We returned to our school and Khansaheb started singing a thumari in which he painted a vivid tonal picture of the beauty we had met…

…Khansaheb was whimsical. If the audience was up to his expectations he could give an unsurpassable recital. But if the atmosphere, or something else, was not absolutely right he would make do with an offering of thumaris. In 1945, at a recital at Kolhapur, the percussion accompaniment did not come up to his expectations. Consequently, he wound up the pure classical part in the first forty or forty-five minutes and started singing thumaris. He was upset by his having given a lacklustre recital. He returned to his lodgings (at Deval Club) around 2.30 a.m. followed by fifty to sixty members of the audience. Khansaheb said to the people, “All right now, you sit here in the verandah. I shall sing for you.” He asked one of his disciples to provide basic percussion accom- paniment on a dagga and took up his favourite musical instrument swaramandal in his lap. He started singing and went on till 6 a.m. Theatre-goers on their way home heard his voice and came to Deval Club to hear him. They stayed on to enjoy the music until Khansaheb stopped singing. No one was in a hurry to get home. There was a similar incident at Belgaum. There too the main recital did not go well. Khansaheb, anxious to catch the 5 a.m. train to Bombay, went straight to the railway station – followed by the usual crowd of inveterate music lovers. The percussion maestro Thirakawa, was also there. Everybody made himself comfortable on the railway platform and Khansaheb started singing. The recital began at 3 a.m. and continued until the arrival of the Bombay train. The unplanned audience, in its final stages, numbered some two hundred people who went home when the recital ended. Needless to say, the voluntary recital was incomparably successful – unlike the earlier (paid) one…

…My relationship with Khansaheb was extremely cordial. So I had no hesitation in questioning him about the variable quality of his recitals. I said, “Khansaheb, your presentation of khayal music seems to be lacking in order. You do alapi for some time. Then you take up notation (sa, re, ga, ma etc.) and before the listeners quite realize what you have done, start on tanas. After some time, you once again turn to alapi. Consequently, other musicians consider your gayaki outside any gharana discipline.” Khansaheb heard me out and said, “I won’t answer you in words but by my music. Listen, I am going to sing raga Darbari.” He presented that raga for forty-five minutes so beautifully that I could not find a trace of his usual untidiness. His first twenty minutes were spent in alapi, so relaxed and leisurely that the listener would begin to wonder whether Khansaheb was incapable of producing a single tana. The first part consisted entirely of charming gestures and alapi in which he glided from note to note. There were no twists or turns or the tiniest of harkats. The bol-anga that followed was equally beautiful. Finally, he ended with spiral tanas which reminded one of cannon fire. I asked him, “Why don’t you sing like this always?” He replied at length: “Because all are not discerning listeners like you. I am a Punjabi and people think of me as a musician who is adept at harkats of Punjabi style and good at notation (sa, re, ga, ma). I am also known for my powerful tana. If I do alapi as I just did, within a short while listeners begin to look displeased as if they were saying to themselves, ‘Why is Gulam Ali singing today like a singer lacking in guts? What we have come for is some fireworks, fast tanas and harkats of Punjabi flavour. This man is wasting his time in alapi!’ When I see the audience getting fidgety I lose my concentration and then give it what it wants. But all the same, what you say, Deodharsaheb, is true. I am sometimes guilty of untidiness in my presentation. It is true. I do realize it, but am somehow powerless to check it”… Khansaheb was temperamentally very cheerful and a god-fearing kind-hearted person. He was invariably touched if he encountered an abjectly poor or helpless person. On his daily visit to Chowpatty he made frequent stops to hand out money to beggars. He would put his hand in the pocket and hand out whatever he found there, be it a few annas, a rupee or a five-rupee note.

Khansaheb was an uncomplicated person – even a little naive in some matters. It was not in his nature to tell lies and deceive anyone. At one time I did not know that he had once been a sarangi player. One day, he happened to see a sarangi in our school and immediately started playing it. He, of his own accord, told me that at one time he had had to support himself by playing that instrument. When he told me about the privations he had to undergo and the circumstances through which he had to pass there was not the slightest touch of self-consciousness about him.

Whenever we engaged in a chit-chat on Chowpatty sands, a small crowd of music lovers would invariably gather round us. On one such occasion Khansaheb started singing. Within a short time he had an audience of thirty or forty people round him. They were all greatly delighted with his music. Khansaheb’s glance happened to fall on a paanwala who had also left his stall to listen to him. Khansaheb said, “Did you see how music makes you forget everything? This paanwala has been standing here for a long time oblivious of the fact that he must sell paan to make a living. The crowd will melt away when the show is over but the poor chap would have lost the evening’s business. I must do something for him.” He then called the paanwala to his side and asked him to serve paans to every one of the thirty or forty people present, at his expense.

Khansaheb had a keen sense of humour. In 1945 he had to go to Kolhapur for a recital. I accompanied him. At Dewal Club, where we were staying, tea was brought in the morning in somewhat diminutive cups. Khansaheb was amused to see such tiny cups. He turned to me and said, “Deodharsaheb, what is a man of my size going to do with this minute quantity of tea? It is barely enough for one sip!” He ordered an entire pot, drank his fill and treated all others staying at the club to tea. During that visit he decided to go shopping for some vests. He visited several shops but was unable to find one large enough for his size. Finally he found one single garment of the requisite size at a shop. Khansaheb said to the shopkeeper, “What kind of a city you have here! I cannot find a vest I can wear!” Khansaheb was a spend- thrift. Whenever he was flush with money he would indulge in an orgy of spending. Naturally some people took advantage of his gullibility and extravagant habits. But Khansaheb rarely complained. He would say, “Fate earmarked the money for them – so they got it.”

Khansaheb’s fondness for food is well known. It is true that he loved good and nourishing food. If he happened to be hungry and food was late in coming he would become visibly disturbed. But stories about his gargantuan appetite, for example that he habitually polished off four chickens and fifty rotis, were largely apocryphal. I can vouch for the fact that he was not a glutton. It was his parasitic companions who gorged themselves on his food and spread stories about his huge appetite.

As Khansaheb was a Pakistan national he had to return to Pakistan when his visa was about to expire. He had innumerable admirers in India and he was in great demand all over the country for concert performances. Consequently he was inclined to take up Indian citizenship which was not easy. Those who were originally residents of what became India but migrated to Pakistan for security reasons could regain their Indian citizenship. But Khansaheb, being a resident of Lahore (in Pakistan), was unlikely to be able to acquire Indian citizenship.

On one occasion, Khansaheb gave a recital at the residence of Morarji Desai when the latter was the Chief Minister of Bombay. Morarji was greatly pleased with the recital. Khansaheb, seeing this to be a good opportunity for bringing up the subject of his citizenship, said to Morarji, “I am really more fond of India than Pakistan. There are thousands of people here who love my music and I should very much like to settle down here. But because I come from Lahore (which makes me a Pakistani national), I have to obtain a visa for coming to India. When the period of the visa, which is some seven to eight months, is over I have to return to Pakistan.” Morarji heard him out and said, “Khansaheb, if you wish to live here and are determined to become an Indian national let me know. I shall try to arrange it.” Khansaheb having made a declaration to that effect, Morarji got him to make a formal application which he forwarded to Delhi with his own recommen- dation. Khansaheb succeeded in acquiring Indian citizenship in 1957-58….