Vasantrao Deshpande

(1923-1983)

About Vasantrao Deshpande

This article has been made available by Dr. Veena Nayak who has translated it from the original Marathi article written by Ramkrishna Baakre.

From: Veena Nayak

Subject: Dr. Vasantrao Deshpande – Part Two (Long!)

Newsgroups: rec.music.indian.classical, rec.music.indian.misc

Date: 2000/03/12

Presenting the second in a three-part series on this vocalist par excellence. It has been translated from a Marathi article by Ramkrishna Baakre. Baakre is also the author of ‘Buzurg’, a compilation of sketches of some of the grand old masters of music.

In Part One, we got a glimpse of Vasantrao’s childhood years and his early musical training. The article below takes up from the point where the first one ended (although there is some overlap). It discusses his influences and associations, his musical career and more importantly, reveals the generous and graceful spirit that lay behind the talent. The original article is rather desultory. I have, therefore, taken editorial liberties in the translation and rearranged some parts to smoothen the flow of ideas. I am very grateful to Aruna Donde and Ajay Nerurkar for their invaluable suggestions and corrections.

Veena

THE MUSICAL ‘BRAHMAKAMAL’ – Ramkrishna Baakre (translated by Dr. Veena Nayak)

It was 1941. Despite the onset of November, winter had not made even a passing visit to Pune. In fact, during the evenings, one got the impression of a lazy October still lingering around. Pune has been described in many ways by many people, but to me it is the city of people with the habit of going for strolls in the morning and evening. In 1941, Tilak Road was not bustling with vehicles as it is today. Rikshawaalas rushing headlong like wild boars were completely absent. Bicycles were the popular mode of transportation those days in Pune. Hordes of bicycles could be seen speeding down the entire length of Tilak road; yet one did not need white lines in order to be able to cross the road. Several bungalows had begun sprouting in the area beyond S.P. College, in the direction of Swargate. The place however, had not developed enough to indicate a settlement or colony. Music concerts were held at Hirabaag but they were not for ordinary folk. However, the corner there was definitely someone’s choice for a rendezvous.

It was at this corner of Hirabaag that one found, unfailingly at around 5:45 p.m. everyday, an old man standing in wait for a young man. A round black cap slightly askew on his head, a gleaming, proud forehead, neatly trimmed moustache, a close-collared, usually snuff-coloured, woollen coat, the large-pleated brahmaNi dhoti worn slightly below the knees, and a heavy walking stick in hand. Standing in the corner, he cut quite a dashing figure. The world of music knew that person by the name of Gayanacharya Pt. Ramkrishnabuwa Vaze. It would, of course, be unthinkable that the people of Pune would not recognize the figure standing in the park. Many would greet him. Buwa would acknowledge them and greet them in return. His sharp eyes, however, would be peeled for the arrival of the youth riding a bicycle along the Swargate side of the park.

The young man was equally smart-looking. He possessed the grace and bearing of a professional athlete. Every morning he would go for physical training at Shiva Damle’s Maharashtra Mandal on Tilak Road. About twenty-one years of age, he was not as radiantly fair-skinned as Buwa, but his complexion was considerably light. Hence, the vermilion marks applied to the earlobes in the morning were still prominently visible. His Nagpuri-style dhoti with its broad border was fashionably worn with its tuck tied fast and with a scout-style khaki shirt on top. Like a whizzing taan, the bicycle would enter the park and, with an abrupt halt in front of Buwa, the rider would disembark. Buwa would complain,

“Arre Vasanta, do you know what time it is? It took you so much time to reach Hirabaag from Vaanwadi? I have been waiting so long for you!”

“It’s a military accounts office, Buwa. Unless the boss leaves, I cannot budge from my desk.”

“Come on, don’t waste more time.”

The pair would then begin its rounds. Even at that time, Vasantrao was capable of singing soul-stirring music. The friendship with Vazebuwa, however, was not based on music. Buwa did not even have an inkling that Vasanta could sing. Buwa knew Vasantrao only as the Nagpuri youth who lived in a rented room next door, worked as a clerk, had a passion for physical training and was also a first-rate gourmand. With the exception of music, they would engage in discussions on countless other matters of the world. Vasantrao was as appreciative of Buwa’s predilection for food as he was of his music. At the break of dawn, Buwa would toss a rupee-coin in a silver bowl and one of his students would be dispatched on the urgent mission of purchasing fresh butter. Once the full bowl was brought home, its contents would be emptied into a stone mortar. Adding a cup of confectioner’s sugar, the student would then sit and stir the mixture. When the butter and sugar were nicely blended, it would be served in the large bowl to Buwa. The remnants in the mortar would be swallowed up by the students. Buwa, however, would savour the butter-sugar mixture in a leisurely fashion, licking it with his index finger, like a devotee whose slurps of water punctuate the chanting of the mantra, ‘keshavaaya namaha, narayanaaya namaha’. These evening strolls taken together by Buwa and Vasantrao, what were they all about? Gluttony, of course.

“Vasanta, let’s go to Govardhan MandaL. They would have just finished milching and if we go right now, we’ll be able to get fresh milk”, Buwa would declare. They would gulp down half a litre of milk each at the MandaL (The metric system was not used in those days; I am using “litre” here just to give you a quick idea). Outside on the road, they would encounter the banana vendor. A dozen bananas would be split between the two men. Buwa would carefully save two bananas in his pocket. It was only when they had seated themselves on a bench in Mathura Bhavan that the purpose of the reserved bananas came to light. Mathura Bhavan, a restaurant in Budhwarpeth, is as famous for its steaming hot fritters as it is for its “doodh ki loTi” (tumbler of milk). Buwa and Vasanta would polish off a huge pile of fritters right there. The bananas hoarded in Buwa’s pocket would then make their appearance and take a dip in the frying pan. “A sweet morsel for a finishing touch!”, Buwa would proclaim as they ate the fried bananas. It turned out not to be the “finishing touch” after all. Opposite Mathura Bhavan was a little shop that sold ‘baasundi’ (a Maharashtrian delicacy made of sweet evaporated milk – VN) which was served in leaf-cups. Their meal wouldn’t be complete without a final course of baasundi, which they did the utmost justice to.

How this friendship, based on shared neighbourhood and love of food, moved into the realms of music, is a profoundly touching tale. For almost two and a half years, Buwa

had no idea that Vasanta could sing a note, leave alone present a full-fledged khyal. Vasanta on his part, however, would regularly sit in while Buwa taught his students. He would assemble paan for himself from Buwa’s plate. One day, Vasantrao found one of Buwa’s students in a strange condition when he visited the latter’s home. In those days, one did not have the straps that spondilitis patients now wear around the neck. However, the student had something wrapped tightly around his throat.

Vasantrao enquired, “What happened to your throat? Some new ailment?”

“Nothing yet”, the student replied, “but I do this in order to prevent future ailments. As soon as I get home, I tie a pouch filled with sheera cooked in fresh ghee.” (sheera = a sweet dish made with cream of wheat or farina – VN)

“A bandage of warm sheera everyday”?

“I have no other choice”, said the student.

“Is the taaleem causing strain?”

“Yes. Buwa gives taaleem in paanDhri chaar and paanDhri paach. Such high notes are beyond me.”

“Then why don’t you just tell him frankly to lower the pitch?”

“What right do I have to say that to Buwa? He would stop my taaleem right away. As it is, I owe him a great debt as he is teaching me free of charge with my current financial state in mind.”

“So what? Your voice will be ruined for the rest of your life! You must tell Buwa clearly.”

“Impossible! I couldn’t do it, not in this lifetime.”

“Then I’ll tell him. Shall I?”

“Please, no. It will be taaleem-hatya for me”

“We will see. I will settle this matter tomorrow itself.”

Next evening after the daily walk, the student’s lessons started as usual. Buwa began singing with his heavyweight gamaks. Vasantrao immediately confronted him. He said, “Buwa, what a plight you have reduced this poor fellow to! Once he goes home, he has to tie a bandage of warm sheera around his throat. Can’t you lower the tonic a couple of pitches for his taaleem? On hearing the question, Vaze Buwa’s eyebrows knotted into a frown and his voice rose even higher! Hurling a choice expletive he said, “What do you, a wrestler, know about a couple of pitches higher or lower?”

“Buwa, don’t say that!. Hum bhi kuch nahin! I will sing anything you ask me to: khyal, tappa, thumri, bhajan. Right now, in this baithak!”

“Vashya~~~~, what are you blabbering about? You sing?!!”

“Of course! And with great abandon! Ok, I’ll show you. Come on guys, set the taanpuras a half-note higher!”, Vasanta ordered the students.

Buwa was beside himself with amazement. “You will sing in black four?!!”, he exclaimed.

“I can sing in (black) five too, but four will do for now.”

When Vasantrao began singing a khyal, Buwa’s eyes eloquently expressed his emotions. As Vasantrao’s youthful, intoxicating manner, his vitality and intelligence, his melodiousness unfolded before him, Buwa began to cry profusely. He was sobbing like a child! The hot embers of anger and anguish burning within him were flung on his students.

“Get out of my sight, all of you! Only Vasanta will remain here.”

The tears had not abated. Still crying, he said affectionately, “Vasanta, does it befit you to act this way? You have been in my company for two and a half years now. You sing so well. Didn’t you even once feel that you must learn a cheez from me?”

“To tell you the truth, Buwa, I brought along so much baggage when I came to Pune that I have not yet sorted it out. When I have not tidied up and properly arranged what is already within me, why bring in something new from outside and throw it into the mess? So I didn’t ask you for a new cheez.”

“But why did you not utter even one syllable about music in all these months with me? Did you think I would forcefully stuff a cheez down your throat? You played hide-and- seek with an old man like me! Does this behoove you?”

“I have those privileges with you, Buwa. If a grandson does not tug his grandfather’s moustache, does not play hide-and-seek with him, who else will?”

“I, your grandfather?! How is that?”

“You are Master Dinanath’s guru and Dinanath is my guru. Don’t these relationships make you my grandfather?”

The grandson had silenced his grandfather. Vasantrao has similarly silenced many in his lifetime.

In the early half of 1940 when Vasantrao arrived in Pune, the world of music in that city was bustling with reputed personalities. One could count these luminaries like the large Maruti temples that abound in Pune. Step out of Shivajinagar station to find Pandit Mirashibuwa, turn left at the Shaniwarwada and go towards Appa Balwant Chowk to meet Pt. Vinayakbuwa at Jamkhindikar’s bungalow, Patankarbuwa at the late Bhaskarbuwa’s Gayan Samaj, Vazebuwa at Bharat Itihaas Mandal, Master Krishnarao behind Maharashtra Mandal, Keshavrao Bhole and Hirabai Barodekar in the vicinity of the wild sadhus, Sureshbabu at Shukrawar, near the wooden bridge was Ustad Mohammed Khan, son of Kadar Bux, the sarangiya of Gandharva Natak Mandali. Bhimsen Joshi had yet to start dropping in at Vaidya Pandurang Shastri Deshpande’s house in Shukrawar for riyaaz. Sawai Gandharva was bedridden after a stroke of hemiplegia.

Such was Pune, a garden in full bloom! Vasantrao, however, chose Sureshbabu (as his teacher. The reference is to Sureshbabu Mane, son of Abdul Karim Khan – VN). In spite of Dinanathrao’s pronouncement that Sureshbabu was a cursed artist whose teaching would not take a student too far, Vasantrao went to Sureshbabu with the inner conviction that the music that he wished to learn was vested in him and none else. “In the decade between 1942 and 1952, I began to understand music”, Vasantrao had once said. If we bear in mind that Sureshbabu passed away in 1953, it becomes clear that he played a significant role in Vasantrao’s musical development.

Learning music and understanding music are two entirely distinct matters. Vasantrao picked up Dinanathrao’s gayaki by going back and forth between Nagpur and Amravati. Years later, in 1938, Vasantrao went to Lahore with his uncle who was transferred to that city during his tenure with North Western Railways. I do not know which half-wit coined the phrase, “Matulaha sarvanAshaya” (“Maternal uncles are a source of ruin”). Vasantrao’s life shows that the saying ought to be amended as “Matulo bhaagyavrudvaye” (“Maternal uncles enhance fortune”). It was Vasantrao’s uncle who entrusted him to Dinanathrao. It was also his uncle in Punjab who gave him strategic advice on how to glean musical treasures from the likes of Asad Ali, Barkat Ali and Bade Gulam Ali. It is greatly enjoyable to hear Vasantrao recount the tales of his wandering days in Punjab.

In 1938, Vasantrao came to Lahore on the railway pass that his uncle had sent him. Gandharva Mahavidyalaya was situated in Lahore, but Vasantrao went there only occasionally and for social purposes at that. Patiala gayaki had enamoured him and he began to take delight in its search. In the course of his wanderings at the koThas of dancing girls, he learnt that an excellent saarangiya such as Haider Bux would take the landlord’s buffaloes to pasture in the forest with a sarangi nestled under his armpit. As the cattle grazed unhurriedly, Haider Bux calmly did his riyaaz under a tree. At nightfall, he would take off to the brothels to ‘accompany’ the dancing girls. He earned his daily bread through these jobs. Such instrumentalists were called Mirashis. The fact that a Brahmin talked to the Mirashis so openly was a source of annoyance to the Arya Samajists. Vasantrao was part of a small group of people which was deeply involved in music. They were greatly sympathetic of the musicians in Lahore, especially Bade Ghulam Ali Khan. Once they planned a felicitation ceremony for Bade Ghulam Ali. Donations were collected. Their utmost efforts yielded a sum of forty rupees but they were not discouraged. A hall was rented and a silk scarf worth 75 paise was purchased. A horse- drawn carriage was engaged for Khansaheb’s transportation. Five rupees were thus expended and that left only thirty-five rupees! Bade Ghulam Ali sang with great love and affection. After listening to his music to their hearts’ content, it was Vasantrao who had to step forward to present him the thirty-five rupees. Handing over the cash nestled in the folds of the silk scarf, Vasantrao said, “It is our misfortune that we were able to collect only thirty-five rupees. Please do not be offended.” Bade Ghulam Ali, with tears in his eyes, replied, ” Why should I feel offended, my son? The people of Lahore do not give me even that much respect!”

That was in 1938. Six years later, Bade Ghulam Ali’s performance at the Vikramaditya Conference in Bombay earned immense fame. He achieved a marvellous feat that was practically unheard of: he sang Puriya right after having presented Marwa. After that conference, the lines of his destiny became distinct. For as long as Vasantrao was in Lahore, he got to listen to Bade Ghulam Ali every once in two days. In addition, he would got to Barkat Ali’s house to listen to his evocative thumris. Barkat Ali was very popular, unlike Bade Ghulam Ali whose fortunes had yet to take a turn for the better. The caliph of the Patiala tradition Ustad Asad Ali had become a fakir and was living in a durgah. A sanyasi of Islam, if you will. Vasantrao would go to the durgah in order to obtain cheez-s from him. He would get one cheez in exchange for one paisa. “Write it down”, Asad Ali would say. Thus, over a period of forty days, Vasantrao collected forty cheez-s for forty paise and one day, he proudly showed the notebook to his uncle, who said, “Now you should do just one more thing.”

“What is that?”

“Throw this notebook in that fire where we heat the water.”

“Why would you say such a thing? I have gone religiously to the durgah everyday to collect these cheez-s from Asad Alikhansaheb and you ask me to burn them?!”

“One doesn’t learn music by copying down cheez-s in this manner.”

“Then what do you suggest?”

“Do as I say. Go to the durgah tomorrow with gifts such as a nice garland, about a sher of mithai and eight-annas worth of charas. Offer them to him at his feet and insist that he teach you with proper ganda-bandhan. Then see what happens!”

Vasantrao was eighteen years at that time. Taking two rupee-notes from his uncle, he proceeded to the market. In Lahore those days, one could purchase a tola of charas for two paise. Ten annas commanded a sher of sweets made in pure ghee. When Vasantrao asked for 50-paise worth of charas, the shopkeeper’s eyes almost fell out of their sockets. He said, “Bada jigriwaala dikhaayi deta hai ladka! Itni si umar mein yeh shaukh!” (“This kid is something! Such a habit at so young an age?!”) Armed with all the paraphernalia, Vasantrao went to the durgah. Assuming that the boy wanted, as usual, to transcribe a cheez, Khansaheb said, “Aao beta, likh lo”. “Oh no, Khansaheb, today I have not come here to copy a cheez. I am here for a different purpose. Whatever cheez-s I had written down from you, I have thrown them in a well. Please grant me the favour of tying a ganda and teaching me formally.” As he was making this request, Vasantrao was unwrapping the packets he had brought with him. On beholding the sweets, charas, etc., Khansaheb probably felt as though he had entered Alladin’s cave. His eyes could not contain his joy. He signalled to five other fakirs who were also present in his durgah. All of them gathered around. They knew exactly what had to be done. Like anesthetists who get to work once a patient is laid on the operating table, the fakirs began making their preparations. Smoking charas is a strange ritual indeed. The coconut oil, the lamp, the long pipe, the practice of lying on one’s side as the smoke is inhaled, so much ceremony! All these were duly completed. The fakirs were by now floating high up in the air. Then they began eating the sweets. Poor Vasantrao sat on the edge of a well in front of the durgah and watched the proceedings. He was joined there by Khansaheb and the rest of the fakirs. The ganda-bandhan was performed.

Khansaheb suggested, “The evening is almost upon us. Shall I teach Marwa?”

“Sure, please do.”

“Why don’t you begin? Show me how you sing.”

Vasantrao began to sing Marwa. he sang the raag to the extent that he knew it at the time. The five fakirs, in their full-throated and robust manner, continued the raga after Vasantrao. The honour of the last position in this succession of singers, of course, belonged to Khansaheb. As he sang, he imbued Vasantrao with a personal realisation that the sole purpose of the shuddha dhaivat is to endow an dusky, contemplative quality to a raag separated from shadja-pancham, a raag that repeatedly portrays the longing of the komal rishabh. At that moment, Vasantrao felt that his efforts, not only of that particular afternoon, but ever since he had come to Lahore, had borne fruit. For four to five months in the durgah, he received taaleem only in Marwa. Many people may have experienced the introspective state that descends on listeners when Vasantrao begins to sing Marwa. I remember a concert in an air-conditioned hall at the Indian Merchants Chamber in Bombay, where Vasantrao, accompanied by P.L. (Deshpande – VN), held one thousand listeners deeply engrossed in Marwa for one and a half hours. The roots of his Marwa can be traced to the ganda-bandhan at Lahore.

Was there a musical gift that Punjab did not bestow upon Vasantrao? It was here that he formed a friendship with Ashiq Ali, the son of Fateh Ali who was known as ‘taan ke kaptaan’. Ashiq Ali fostered such an invaluable treasury of bandishes that once Roshan Ara, on her way back from a programme in Lahore, stopped at his place, unloaded her luggage from the tonga and cancelled her ticket just so that she could garner his bandishes. Vasantrao must have learned a lot from Ashiq Ali. Vasantrao spent the time from ’38 to ’40 travelling from Lahore to Varanasi, making numerous stops on the way. During 1938 to 1942, he trained his voice through riyaaz in the Meerkhand tradition. From 1942 to 1952, Vasantrao kept frequent company with Sureshbabu, Kumar Gandharva and Bhendibazarwaale Aman Ali, and gained musical insights from them. It is natural to ask why he did not make a full-fledged entry into the music profession in 1953, by which time he was an accomplished musician. Why did he wait until 1965 to quit his job with Military Accounts, to declare, “Now it’s the tambura and I”? One reason might be that he did not want to depend on music for a livelihood. Furthermore, he perhaps believed that although he had understood music, there were still a lot of experiments to be tried out. The job at Military Accounts was a low-paying one; nevertheless, it assured a steady flow of income. Once he had fulfilled his household obligations, he was free to pursue his musical ideas and experiments. Be that as it may, Vasantrao’s friends in the musical field were impatient and eager for him to leave his number-crunching job and fully immerse himself in music. In fact, Akbari Manzil in Lucknow was anxiously awaiting this moment for many years.

The reader may, at this point, wonder how Lucknow comes into the picture. The Empress of Ghazal, however, was constantly pestering Vasantrao in her letters to give up his job. I had heard that Vasantrao and Begum Akhtar had exchanged a significant volume of correspondence. When I asked him about it, he said, “I burnt all the letters.”

“Why did you do that?!”

“On 30th October 1974, I read that Begum Akhtar had passed away in Ahmedabad. This was a natural reaction to the news.”

“Alas! You should have saved that correspondence, Vasantrao.”

“For what? Our interaction in those letters was on a personal level. Why should it be saved? I treasure the music that she left behind. It is the only thing that needs to be preserved. ”

“But those letters might have been useful to some author such as the one who wrote ‘Vishrabdhasharda’….”

“That is exactly what I wanted to avoid. Why display those letters in front of the whole world?”

“Begumsahiba used to address you as Guruji, didn’t she?”

“Bhai (P.L. Deshpande) had written (about) it sometime. I too felt the same about Begumsahiba. Art and knowledge are often inadvertently exchanged between generous and creative minds. This enhances the respect they feel for each other. Why get fixated on such titles, Tatya? Great people just say these things..”

“When did you first meet Begum Akhtar?”

“In 1935. It would be more fitting to say that she got to know me rather than the other way round. I was only fifteen years old then. I used to visit Nagpur during Tajuddin Avaliya’s festival in order to seek his blessings. She too had come there for the same reason. She is about three years older than I am. I used to attend every programme at the festival. Would push my way through and sit in the first row. At one point in Bai’s recital, she negotiated a difficult turn very well. I was the only one to appreciate it and I exclaimed my approval so loudly that she noticed it. Later, she enquired around about the boy who seemed to be know so much at such a young age. Thus, we got acquainted and subsequently became good friends. If she was visiting Bombay, I too would come to Bombay. In Pune, Madhu GoLvaLkar, P.L., and Bai used to stay at Ram Maharaj Pandit’s place. Bai would sing through the night sometimes. Her music is engraved in the walls of that bungalow. In every letter that she wrote to me, she would insist that I quit my clerical job and become a full-time musician. Such a thing was not feasible for me until 1965. In 1964, I was transferred to NEFA. I suffered as though I had been punished with Kaala Pani. I felt like a fish out of water. At that point, I decided that, come what may, I had to free myself from this service profession.”

Vasantrao endured the Kaala Pani for almost two years. His exile to NEFA (at the north- eastern frontier) was like a sharp, bitter thorn in Bai’s mind. Once she heard that Vasantrao was going to Assam via Lucknow in the company of his colleagues. As soon as Vasantrao got off the train at Lucknow to stretch his legs, he found Begumsahiba in front of him. In her hand was a first class ticket that she had just purchased. It was in Vasantrao’s name and was a reservation on the train that left for Assam two days later. Waving the ticket at him, she said,

“Come on, Deshpande Saheb, Akhtari Manzil awaits you! Stay for two days and then go on to Assam. I have even reserved the ticket for you.”

“Afsos! How is this possible, Begumsahiba? I am travelling with the office unit. If I don’t go with them, the commanding officer will arrest me and take me away in handcuffs. This is the military profession, not a regular one. I am extremely sorry..”

Vasantrao left with the unit on the same train. Truth be told, Begumsahiba had no reason to be unaware of the ways of the military. Her brother-in-law, Barrister Ishtiaq Ahmed Abbasi’s maternal cousin, Major General Habibullah was in a top post in the military. Nevertheless, she did not understand (Vasantrao’s situation). Bai was vexed that Vasantrao had left without accepting her hospitality. The events that followed this incident are the stuff that great dramas are made of.

About fifteen days after he had returned from Lucknow, a telegram in Vasantrao’s name arrived at his office. The Commandant opened it, read it and probably got a little suspicious. He took it to Vasantrao’s desk. On reading the contents, Vasantrao understood. Ever the skillful drama actor, he invoked an expression of utmost seriousness on his face. Even some tears in his eyes. What was the message in that telegram? “Mother serious. Start immediately.” Only four words and at the bottom, in place of a signature, was just one letter! “B”. The Commandant asked,

“Whose signature is that?”

“Sir, it’s my daughter’s. My eldest daughter. We call her ‘Baby’ and I personally call her only by one letter, B.”

The Commandant was easily taken in by this explanation and by Vasantrao’s acting. Vasantrao was choking even as he was providing the explanation. As soon as he heard the Commandant announce that he had been granted a ten-day casual leave, Vasantrao destroyed the telegram. Immediately, he set out in search of a convoy to Dibrugadh. For the service personnel in NEFA, official leave goes into effect, not on the day that the worker leaves the office, but only when the worker has boarded the train at Dibrugadh. The medical unit’s convoy to Dibrugadh was the quickest. Vasantrao used that convoy and then, some hours later, leisurely stepped out on the railway platform in Lucknow.

Begumsahiba was, of course, waiting there to welcome him. After the first burst of laughter had died down, Vasantrao asked, “Is that the way to sign a telegram?”

“Why? What happened?”

“Why did you write just “B”?”

“Should I have written just Begum Akhtari then? You are splendid, Deshpandeji!”

“That wasn’t what I meant. Why didn’t you use some neighbour’s name? The Commandant was definitely suspicious.”

“Really?”

“You think I am lying? There was another mistake too —”

“What was that?”

“I am from Pune. You sent the telegram from Lucknow!”

“I had no other option, Deshpandeji. How could the Lucknow post office give me a Pune stamp? But surely the Commandant didn’t read the stamp?”

“I am lucky that he didn’t. Or else..”

“I thought these officers read only the contents. How am I to know that they look at all these details? Anyway, you did get leave, right?”

“Yes, I did.”

“How many days?”

“Ten!”

Begum Akhtar was delighted. Reserving two days for travel, Vasantrao was able to stay at Akhtaribai’s house for eight days. O, the hospitality that Bai showered on him! As long as there was a mehfil (and in those eight days, it went on almost continuously), Bai would station four persons at four different directions just to assemble paan. She had all her taiyyar students sing for him, not just once, but many times over. Akhtaribai’s husband was extremely religious. He would do namaaz five times a day. Despite having a pile of silver vessels in the house, he would drink water from a plain tumbler. Bai was prohibited from singing in Lucknow but not in the rest of India. In those eight days, Vasantrao heard her music to his heart’s content and himself sang for her. Eight days flew by without his realising it. He was in his own little musical world blissfully oblivious to everything else. The sun rose and set without in any way disturbing his rhythm. Eight days later, Vasantrao awakened from the dream and came to reality. Begumsahiba went to the station to bid him farewell. Again and again she urged him, “ Deshpandeji, do whatever it takes, but resign from this job.” It finally happened in 1965. Everything fell neatly in place when Vasantrao was deemed ailing and unfit for service. He began to draw the invalids’ pension. Begum Akhtar ensconced herself in Pune to make sure that everything was proceeding according to plan.

Taking an impartial view of Vasantrao’s life, one cannot but feel that he is a brahmakamaL in the garden of music. The brahmakamaL bursts into bloom at midnight. One has to wait a long, long time for such a midnight. Europeans call this flower, ‘The Star of Bethlehem’. It is their belief that Jesus Christ sleeps in the pollen sac of this flower and that each grain from this sac radiates, like a star, a ray of fragrance on his body. They attentively wait months on end, for the lotus bud to blossom and shower fragrance into the air. As the moment of bloom draws near, they circle around the bud and dance euphorically to the rhythm of clinking champagne bottles. Until Darvekar’s ‘Katyaar’ (note: the reference here is to the drama, Katyaar KaaLjaat Ghuslii, where katyaar = dagger – VN) was unsheathed, Vasantrao’s star was yet to explode, people had yet to dance around him. Prior to Katyaar, Vasantrao went through life embodying the attitude “vaatevar kaate vechiit chaalalo, vatale jase phulaat chaalalo. (I gathered thorns along the way and thought I walked among flowers). He had been a playback singer and had brightened many a mehfil. He had played the role of AshwinisheTh in sixty performances of Sa.nshaikalloL and had accomplished wonders with songs such as ‘Maanili Aapuli’ in Raag Shukla-Bilawal and ‘Mriganayana’ in Raag Darbari, songs that were considered inferior by the classical elite. During special training sessions with Asha Bhonsle, where he trained her to sing ‘Parvashata paash daive’ exactly like Dinanath’s rendition, he had reduced her to tears, overcome with the memory of her father as Vasantrao sang the song.

Vasantrao used to say jokingly, “Singing naatyasangeet is like creating public awareness”. Naatyasangeet, although a familiar territory, is so pervaded with raag music that it confounds an average listener. It is almost as though the ‘De’ in Vasantrao’s surname were a symbol of his generosity of nature. Once he wrote a letter, composed in the form of a bandish, to Kumar Gandharva. He only wanted to intimate Kumar that he was coming to Dewas, but he did so in Raag Madhuvanti. He wrote,

Aavoon tore mandarva

Paiyaan parat deho tore

manabasiya

Main aavoon tore madarva

(Aavon tore mandarva = I will come to thy abode Paiyaa.n parat deho tore = I fall at your feet manbasiya = beloved, one who dwells in my mind)

Kumarji promptly replied in the form of an antara: Arre mero maDhaiyya

Tora aahere

Kaahe dhari charan mero

manabasiya

(mero maDhaiyya tora aahere = my hut belongs to you kaahe dhari charan mero = why do you touch my feet?)

Today this bandish is included as Kumarji’s composition in his book ‘Anooparaagvilas’. Its asthayi is Vasantrao’s, but when asked for permission to publish it, Vasantrao promptly told Kumarji to publish the entire composition in the latter’s own name. It is not because Kumar was an adored idol. He was similarly generous with everyone. Consider, for instance, the case of the drama, Megh Malhar. The rehearsals for Megh Malhar were going on under the direction of Ram Marathe who was responsible for all aspects of the show from casting to music direction. Since Ram Marathe was himself a renowned singer, the producers felt it unnecessary to cast a singer-actor of equal stature in the friend’s role. Rambhau, however, told them in no uncertain terms: first ask Vasantrao; approach other actors only if he refused the role. Vasantrao accepted the offer. Subsequently, Rambhau’s mother suddenly fell ill as a result of which he was unable to commit much time to music direction. Vasantrao devised a solution: “I’ll compose the songs that I have to sing; Rambhau can focus only on his songs.” The question arose, however, as to who would be billed the music director of the drama. Would they have to name two composers in the manner of joint secretaries in politics? Vasantrao said, “Only Rambhau should be named the music composer. He is the captain of this show.”

Due to the Megh Malhar incident, Darvekar and PaNsikar (Marathi playwrights – VN) must have gotten an idea of Vasantrao’s value. Darvekar had asked Vasantrao to read the script for Katyaar. After he had done so, Vasantrao said to him, “If you don’t mind, may I make a suggestion?” “If you suggest something, then it must definitely be a worthy idea!” “From my experience with Khansahebs I know that once they decide not to impart knowledge to someone, they will not change their decision even if it costs them their life. This play is thematically similar to VidyaharaN and I think it should not have a happy ending. It must end in tragedy. What do you think?”

Darvekar rewrote the third act. It is an extremely well-constructed drama. Vasantrao resolved several times to not act on stage again, but he could not keep away. No other actor could have played the part equally well as it was hard to find someone of Vasantrao’s power and calibre. Many times, however, circumstances outside his control compelled Vasantrao to change his decision. When Prabhakar Phansikar fell seriously ill, the fate of all the people involved in Natyasampada fell under a cloud. Vasantrao went to PaNsikar and said, “Until you recover, I’ll work free of charge in as many productions of Katyar as are staged.” Such was his generous nature.

Vasantrao nurtures a state of intense restlessness about music, a constant desire to create or try something new. When he came to know that Baburao Rele had organized a program of only Hori songs for Maratha Mandir’s Kala Vibhag, Vasantrao promptly showed up from Pune for the rehersals. Like an incarnation of Dattatreya, this man has been wandering for the last 45-50 years. In spite of having a full-time job, he would commute from Pune to Deodhar Music School (in Bombay) so that he could be in Kumar’s company. From 1950 to 1952, he travelled back and forth between Bombay and Pune to learn the rhythmic play of sargam (solfeggio) from Aman Ali. It was the constant longing for something new that led Rele and Vasantrao to present in Maratha Mandir a wonderful listening program befitting the monsoon, ‘Ghan Garaje Barkha Aayi’. Even as I write, the two have undertaken a new venture called ‘Surdasaanchi Krishnabhakti’. It is sure to lead to a great music programme.

“Sing as easily as you speak”, was the guru-mantra given to him by Asad Ali Khan and Vasantrao has assimilated it to perfection. There is a world of difference between the gentle Vasantrao before the start of a mehfil and the Vasantrao resplendent and poised in an aggressive stance between two taanpuras. There is one sign that indicates that the khyalia and taaliya in him have been roused. From the flurry of movement at the tips of his index and middle fingers, one could safely conclude that the main switch had been turned on. Subsequently it becomes evident that all chambers have been charged. When Prakash Gore’s tabla begins to follow his singing, Vasantrao’s voice takes on the semblance of a note gliding off the instrument. Sometimes he weaves rhythmic patterns of sargam; at other times he takes flight from a random beat and swoops unexpectedly on the sam, catching the listeners completely unawares. The two strengths of his gayaki are amazing unpredictability and innate ease. An exception is made only in the case of abhangs. These statements of the great saints are sung by Vasantrao in clear, unembellished tones. The sentiment behind this restrained style of rendition was that such songs must not be tainted with unnecessary embellishments such as harkats, murkis or taanbaazi.

In all other types of music, his singing flows like heady champagne. It is not just the listeners who plunge joyfully in its currents. Sometimes his tabla accompanist Prakash

Gore also starts to relish the champagne and ends up committing an error. Once Vasantrao had asked him to play in eight beats in the roopak ang. The first few cycles were played correctly, but subsequently Gore slipped into the role of a listener and got so engrossed that he began playing the simple roopak taal in seven beats. Vasantrao turned to glance at Gore but once, continued singing the cheez and concluded it in seven beats. When the cheez ended, Gore went pale, but Vasantrao did nothing that would introduce confusion in the proceedings. Such was his generosity of spirit that he did not even mention the mistake to Gore. Vasantrao was skilled in enhancing his accompanists by looking out for them and publicly appreciating them at appropriate points. During a Sawai Gandharva festival, when Gore accompanied him for the first time, Vasantrao said to him, “Play as much as you want; we are on home ground today”. At a Parle Tilak Mandir concert he praised Chandu Limaye’s aggressive vocal accompaniment at least six or seven times with, “Wah beta”. In fact, Chandu has made capital out of this encouragement and Vasantrao has even proclaimed Chandu as his musical heir. Vasantrao is such a versatile musician, but until ‘Brihaspati’ had made his exit from Akashwani’s horoscope, he was persona non-grata at the radio station. The justification offered for this status conferred on Vasantrao was that he had not taken the audition! His recordings, however, were unashamedly played on the radio. Who knows why the arrogant department later changed its mind! They implored him to perform a national program. It was only after attaining international fame did a national program come to Vasantrao’s share!

Vasantrao possesses certain traits that are difficult to characterise as strengths or weaknesses. One is punctuality and another is his extreme avoidance of self-pride. He dislikes giving even the slightest hint of matters concerning his own fame and glory to even his close friends. So many of his recordings have been released and a cassette is along its way, but he has never asked for even one ‘retake’. He arrives at the studio a few minutes ahead of schedule and asks only the time at which he has to conclude a song. With his watch placed in front of him, he begins as soon as he is given the signal and finishes in exactly the 3-1/4, 7, 10, 20, etc. minutes that he had been allotted.

Two incidents in the last two years reveal Vasantrao’s opposition to any kind of self- importance. One night at the Sawai Gandharva festival, Vasantrao and Hirabai Barodekar were going to be publicly feted. The felicitation ceremony was at 9:30 pm and Vasantrao was scheduled to sing at 4:00 am in the later half of the night. Baburao Rele, a close friend of Vasantrao from Bombay was staying at Vasantrao’s house for the week. Since he was only visiting Pune in connection with a wedding, he did not know about the felicitation. He merely asked Vasantrao what time he was scheduled to sing. On being informed that it was in the wee hours of the morning, he requested that Vasantrao wake him up and take him along. At dawn, a car arrived to picked up Vasantrao and his guest. Vasantrao sang until 5:30 am. After chatting with Pt. Bhimsen Joshi for a while, everyone returned home by 6:30 am. Rele began leafing through the newspaper and read the news about the honour ceremony. Rele was dumbfounded. He had been staying with the honoree and had not gotten even the slightest hint about the ceremony! It has been said that self-glorification diminishes a person’s merit. It is for this reason, perhaps, that Vasantrao made no mention of the felicitation.

Consider the events that took place before his 61st birthday celebration at the Bal Gandharva Rangmandir in Pune. The function was originally scheduled to be held in

Bombay at the Dinanath Natya Griha in Parle. It was meant to be a surprise for Vasantrao and preparations were being made accordingly. Chandu Limaye had booked the theatre. The plan was to hold a ticketed performance of Vasantrao’s unique three-hour solo programme, ‘Naatyasangeetachii Vaatchaal’. The proceeds from the tickets and donations were to be gifted to Vasantrao. How Vasantrao managed to sniff out these plans is still a complete mystery. He said to Chandu, “ My 61st anniversary celebration is going to be held in Solapur. You and Prakash must attend”. The date of the Solapur celebration turned out to be same as the one that Chandu had reserved the hall for. So Chandu had to spill the beans. Vasantrao said, “I will see to it that the hall is utilised by someone else and you’ll not lose your money. But the ceremony will be held in Solapur and I want both of you to be present”. Thus, with an outright bluff, Vasantrao had put a spanner in the entire works. If he had had his way, he would not have allowed even the Solapur ceremony to take place.

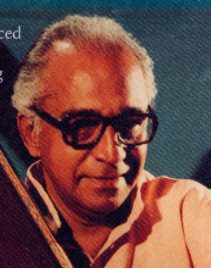

In private get-togethers, Vasantrao is an excellent mimic. One gets an idea of his talent from the photographs shown along with this article. In one of them, we get a glimpse of the late Aabasaheb Mazumdar participating in a mehfil, in another photograph, we see Principal G. H. Ranade. One also encounters the haughty visages of some listeners. I have already mentioned his guru’s advice to Vasantrao: “ Sing as you speak.” Vasantrao has assimilated not only this teaching, but also its inverse. In his speech, he reflects his singing style: straightforward, casual and easy, but quick-witted. A concert listener once slyly asked him, “Are you ever in rhythm with any tabalchi?”. Vasantrao replied in mild tones, “I am always in rhythm. The tabalchi accompanies me only to make sure that listeners like yourself can judge whether I am singing in taal.” At a recent Guru Poornima celebration, Vasantrao was served a plate of laadoos and chiwda, which he declined for health reasons. A reputed doctor who was seated nearby said, “I am here, Buwa. Don’t worry; go ahead and eat it.” “One look at my BP line will be enough to send you into a coma. Then you’ll be of no use to me”, quipped Vasantrao. Another incident relates to his activities on Marathi stage. These days, Vasantrao undertakes only two performances of Katyaar per month, one in Pune and the other in Mumbai. Someone who had come to see him in that regard remarked, “ Marathi theatre is indeed fortunate to receive your service (“seva”). Vasantrao replied, “Why do you want to make it all greasy by uttering words like seva-biwa? I accept these performances for my !@#$ and to earn a living. Marathi theatre will do just fine without me. It will strut along with the vermilion of some other name on its forehead.”

Such is this brahmakamaL, radiating it sweet scent from every grain. The fragrance of a brahmakamaL lasts four an a half hours after its bloom. When applied to Vasantrao, this measure translates into a different length of time. Don’t they say that one day of Divinity is equivalent to a thousand years of humanity? It is hoped that this brahmakamaL will continue to shower its fragrance for another forty years to come.