Asghari Bai

(c.1911-2006)

About Asghari Bai

From Outlookindia.com, January 29, 1997

A Song Of Penury

Bitter and angry, legendary Dhrupad exponent Asghari Bai would sell all her honours for two square meals a day

SOMA WADHWA

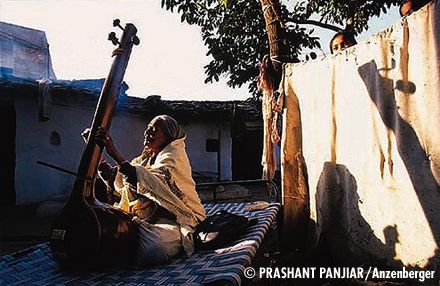

THERE is no music in the air. Only hunger pangs. Only grim complaints. And the melodious voice that once held millions in thrall, is hoarse with anger. “I want the sarkar to take back my Padma Shri! I’ll barter it for two square meals a day. I’ve discovered my family can’t lick it when they’re starving!” These days, songs rarely touch the lips of Asghari Bai, the living legend of Dhrupad and the country’s only woman vocalist in this dying discipline. The unlettered maestro doesn’t know of the books written on her. Nor is she interested in any of the films made on her.

She’d sell them all, she says, to buy a decent lifestyle. Dismissing the Padma Shri, the Tansen and the Shikhar Samman as dusty memorabilia from happier times, the 86-year-old says she now finds little to sing about. “Neglected souls can’t have singing voices,” she pronounces with a sad shake of her grey head. Then, ire wins over resignation, and she turns prophetic: “Beware, I tell you. Art will not thrive in a country that forgets its artistes!” The bitter Dhrupad exponent says that those who would earlier invite her to sing at functions in their modest homes have stopped ever since she received the Padma Shri in 1990. “Now, they feel foolish giving me Rs 51. I am just not able to convince them otherwise,” a frustrated Asghari says. Socially too, the honour has played havoc with her life. Dowry demands for her granddaughters have shot up. “Suitors want money that befits my status. How do I tell them I live in penury?”

Her tired eyes brimming with helpless tears, the octogenarian bids her two invalid sons and young granddaughters to queue up. A timid, unkempt crowd gathers around her. Asghari, the performer, takes her cue. The pitch of her voice rises with each word. And she sets out to shame the philistine world: “Line up my liabilities. Line up, my children, in this ramshackle home of ours. Let musicians of the world know they should be gathering money for their children instead of wasting their youth on music!” Emotions are charged by now. Everyone watches in rapt attention as Asghari’s old finger undertakes a tour of her hutment home. She points to the torn curtains. The empty kitchen. The broken walls. The marriageable granddaughters. The ill-clad grandchildren. The son on crutches. Finally, the finger returns. To brush away tears that can no longer be contained. And, for once, the great musician seems to have lost her voice.

Asghari’s son, Kamaal Khan steps in to help his ammi. Suppressing a dry sob, the 52- year-old adopts a matter-of-fact tone. Ammi receives a monthly Rs 1,500 from the Government. But it comes in a lump-sum every six months and is not enough to sustain her huge family. Former human resources development minister Arjun Singh did help her with a small place and some musical instruments to start off a music centre. But there are few in Tikamgarh wanting to learn Dhrupad. “And ammi doesn’t take money from the few disciples who do come in. Instead she insists on bearing their expenses,” the son says with a tinge of disapproval.

This gets Asghari’s defences up. Singing Dhrupad, she declares, requires enormous stamina that only comes from a teacher’s nurturing care. The guru-shishya relationship is obviously close to her heart, for it has her talking about her own teacher for the next half hour. Each wrinkle in her face gets animated as she remembers him—Ustad Zahur Khan from Gohad. “He had asked for me from my mother when I was eight. I spent 15 years with him,” she reminisces.

Warming to the extraordinary stories to follow, she spits out her tobacco. Coaxes her pet mongoose, Chonna, to snuggle up to her. And talks of her Ustad’s eccentricities. He had ordered her tonsured because she had dared to apply kohl as a teenager. “She who indulges in fashion cannot be serious about learning music, my Ustad felt,” Asghari remembers. He never taught his daughters but only Asghari. “I was the chosen one,” she says with childish pride. But the garrulous woman turns reticent when it comes to discussing her background. Her mother was like Umrao Jaan, is all she is willing to disclose. But gentle prodding reveals matter for a biography that would boggle.

ASGHARI’S mother, a servant with the Raja of Tonk, was gifted to a Tikam-garh courtesan who had a liaison with the raja. “So my mother grew up to be a court singer. I would have too if my Ustad hadn’t taken me under his wings,” she says. It was here that young Asghari learnt the art of Dhrupad with obsessive devotion. Later, she met and married Agra-based textile mill manager Chaman Lal Gupta. “No Muslim would have married me. My in-laws never accepted me. But he loved me dearly,” recalls Asghari. “Till he died of paralysis in 1962.” She returned to Tikamgarh and started making pickles to support her seven children. All of whom she renamed. “We turned Muslim. My brother became Kamaal Khan from Kamal Gupta and I became Anjumara from Anju,” says her Kanpur-based married daughter. “But despite the hardships and our irritation, she kept up with her riaz (practice). It was intolerable to wake up to all those funny noises every morning at four.”

The first break came in 1981, when one of her acquaintances arranged for her to sing at the Allaudin Dhrupad Samaroh in Gwalior. After that there was no looking back. “I was taken to countries I still don’t know the names of and I sang at functions I never knew the importance of. Illiterate and unsmart I never made the most of any opportunity,” the maestro regrets.

Contemporaries like Begum Akhtar went into the popular domain of ghazal and thumri while Asghari remained adamant about singing only pure Dhrupad. “It helped my pride remain intact. But I neglected my children. It got me meetings with Indira (Gandhi) and a picture with the President. But it didn’t help get my family rotis,” the artiste confesses remorsefully, “I was too absorbed in my music and myself to care.”

So amidst state-gifted tanpuras, harmoniums and tablas she sits. Nursing her guilt and grudges. With not a song on her lips. Neither one in her heart. Oblivious, like the rest of us, that the Ustad Hafiz Ali Khan Trust would be announcing an award of Rs 1 lakh for her the very next day. Our following visit, then, may see a different Tikamgarh. There may be music in the air.