About D. Ame’l

From: Music to Thy Ears: Great Masters of Hindustani Instrumental Music by Mohan Nadkarni (Somaiya Publications, 2002)

D. Ame’l

by Mohan Nadkarni

Who was D. Ame’l? If his sudden death in February 1990 passed off almost unnoticed by the music world, it was quite possibly because he himself may have wished it that way. D.Ame’l was the man who, in 40 years of dedicated service to the broadcasting organisation, had become synonymous with the music division of AIR Bombay – a fact which many of avid and old-time listeners may well have overlooked, or ignored or even forgotten.

How many have cared to remember that D.Ame’l was the innovator of 500 odd musical compositions, vocal as well as instrumental, which were the rage of radio listeners of those times ? And whoever knows that most of the signature tunes which are still being played in the scheduled AIR programmes are his creations?

To know more about the pioneering work of D.Ame’l, one has to trace the history of broadcasting itself right from its inception in the late twenties.

To me, the name D.Ame’l – acronym of his real name Amembal Dinaker_Rao – takes me back to those halcyon days in the late ‘thirties and early ‘forties . I was a teenager then, and classical music had almost become an obsession with me. Those were the days when All India Radio was about the sole purveyor of what was rightly hailed as wholesome music – be it classical, light classical or popular – to most listeners.

There were barely half a dozen broadcasting stations in the vast subcontinent and, possibly, next only to the unit in Delhi, the Bombay station catering to the western zone deservedly enjoyed pride of place in the radio network for the high quality of its programmes. Incredible as it may seem today, it was a small group of talented, imaginative and dedicated staff that managed the music division of AIR Bombay. The Bombay station, it would seem, was singularly lucky to have a succession of cultured and perceptive station directors, like Zulfikar Bukhari, his brother, Ahmed Shah Bukhari, B. S. Mardhekar and Victor Paranjoti, to name a few. All of them associated themselves with the programme planners and producers in their day-to-day work. And D. Ame’l was one of the most talented and innovative of producers.

I was one of the old-timers who was never tired of listening to operatic presentation – besides, of course, concerts of raga music – like ‘Karna’, ‘Badkanche Gupit’ or Natashreshtha’, all written by Mardhekar, who was, incidentally, one of the most celebrated names in modern Marathi poetry. And D.Ame’l, who had his grounding in traditional music, was the composer who scored the music for these presentations.

Then there was a series of Marathi, Gujarati, and Kannada songs, styled ‘Saptah Geet’, which were charming raga-based renditions of choice lyrics from popular poets. What was then known as the Bombay Province was a tri-lingual set-up, and the object of the series was to cater to all the linguistic groups. The artistes billed for singing these geets were all popular names of the time. The important point is that these were all the ventures not conceived or attempted before for the purpose of broadcasting. ‘Saptah Geet’ was a series that ran through the whole year and proved to be tremendously popular among all sections of listeners.

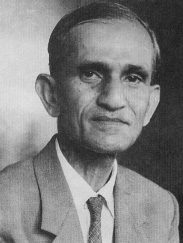

Dinaker Rao (as I always called him) was 81 at the time of his death, and led a quiet retired life at his modest flat near Opera House in Central Bombay. Soft-spoken, mild-mannered and deeply religious, he remained immersed in contemplation, reading and music in that order. In his last few years he had turned deeply spiritual a yogi at heart.

Time was when [the] tall, fair and handsome Rao looked every inch an artiste. His perfectly chiselled features, bright eyes and a sensitive, mobile expression were truly eye-catching. In keeping with those times, he used to be meticulously clad in Western dress, and go about his work, silently and unobtrusively, without throwing his weight about among his subordinates and colleagues, quite unlike most bureaucrats in a government set-up.

Amembal Dinaker Rao came of a cultured and well-to-do Chitrapur Saraswat family from South Kanara in Karnataka. The Amembal family has been known for its love of music and the performing arts. Dinaker Rao’s generation took to music as a joyous pursuit from early childhood. Like him, his brothers have been self-taught musicians. But it was left to Rao to take up music as full-time career.

Rao decided to forsake his academic career in favour of music while he was studying for his final B. Sc. examination at Fergusson College in Pune. While in college, he had already become popular as a singer, who would regale his audiences at college functions and private baithaks (concerts) with his songs. Endowed with an intensely musical and flexible voice, he excelled in singing devotional songs. He had modelled his style on that of the eminent vocalist, the late Master Krishna or Krishnarao Phulambrikar, and had even cut discs for HMV in those days. Side by side, Rao also acquired a thorough command over the harmonium. His urge to be a musician grew so compulsive that he left college to come to Mumbai and in 1927 joined what was then the privately-owned Indian Broadcasting Company, first as a casual performing vocalist and a harmonist, and later as a member of its staff.

When in 1937, the government assumed control of the broadcasting media, Rao was absorbed into the new set-up and made a Programme Executive in charge of Indian music. In the process he completely merged his identity with AIR Bombay till his retirement in 1967. Rao’s services received official recognition of sorts on the occasion of the golden jubilee of Indian broadcasting in 1977. The then prime Minister, Morarji Desai, presented to him a small memento, depicting AIR’s emblem. This was all he got as a token of his appreciation for the work he had done towards building up an important broadcasting unit almost from scratch.

Why Rao forsook a promising career as a vocalist and took to the harmonium remains a mystery. He simply said that he had evinced a keen interest in that instrument because of the influence of his eldest brother, A. Sundar Rao, himself a superb harmonist and a wing- commander of the IAF. Ironically, within a few years of his service with AIR came the official ban on the instrument. This led him to try his hand at the metal flute and also the violin. But he concentrated on the flute for the rest of his life and worked wonders with that instrument in the years that followed.

Dinaker Rao told me that the influence of another brother of his, A. Bhaskar Rao, and his mentor, Master Krishnarao, spurred him on in his creative work, While Bhaskar Rao, a former director in the Films Division, also made his mark as a gifted exponent of light and devotional music, composer and tabla player rolled into one, his guru earned fame as a classical vocalist, stage director and was also a noted composer and music director of several celebrated Marathi films. However, I regarded Rao as basically self-taught, like his other brothers. Significantly, Dinaker Rao’s association and close friendship with two or three of his contemporaries in the field also encouraged him to pursue his quest. The names of B. R. Deodhar, G. N. Joshi and Walter Kaufmann come to mind in this context. None of these three stalwarts is alive. Deodhar was a noted scholar musician and teacher, and Joshi a classically trained composer and innovator who headed the recording division of the Gramophone Company of India (HMV) for more than three decades. Kaufmann, on the other hand, was a conductor and producer of Western music, who derived inspiration from Indian raga music.

It is necessary to mention that Deodhar had built an orchestral ensemble in order to popularise raga music. Impressed by this innovation, Dinaker Rao set up a similar unit for broadcasting purposes in 1935 under the name VUB Indian Orchestra, and began putting out his programmes on the Bombay channel under the pseudonym D. Ame’l . The name of the ensemble came to be changed several times and now it is known as Mumbai Akashvani Vaidya Vrinda. What put this orchestral unit in a class by itself was its composition as well as its manner of presentation. Orchestral pieces were rehearsed thoroughly and notations were dictated to the partnering instrumentalists by Dinaker Rao as the conductor. The artistes took down the notations in their individual but widely varying ways, including staff notations.

What is more, the conductor himself played on his flute in the orchestra, while simultaneously conducting the ensemble. With his two hands engaged in playing his instrument, he simply could not perform as a conductor in the traditional way. All he could do was to memorise his chosen pieces with the help of written notations and yet present his numbers with uncanny accuracy and precision, much to the delight of his listeners. The odd instruments of different groups of string, wind and percussion, made up the ensemble. It also included the Indianised version of the clarionet and the Carnatic gottuvadyam. The compositions presented group-playing, with the partners performing in unison. After each avartana (cycle) came a brief solo interlude, in which the flute, the violin and other instruments took part. The repertoire, too, revealed a marvellous range and variety of ragas, besides tunes based on popular Marathi stagesongs, thumris, Urdu ghazals and naghmas. Fifteen minutes were earmarked every day for this item for several years without break.

It would be fair to mention here Dinaker Rao’s association with Walter Kaufmann. Kaufmann was directly in charge of the Western music division at AIR Bombay. He would obtain some of Rao’s compositions and present them using Western technique, involving harmony and counterpoint. The idea behind such innovations was to introduce simple harmony in Indian music without affecting its innate Indianness. The partnership between the two composers was total and complete. I still remember having heard their joint musical ventures broadcast from AIR Bombay. In point of content, treatment and approach, these held out exciting possibilities. More importantly they spoke eloquently of the innovative acumen of the two composers.

I also have nostalgic memories of Dinaker Rao’s orchestras based on well-known and less-known ragas. These served me as music lessons in these early years of my listening. His self-composed ragas like Ameli Todi and Ameleshwari were also popularised through his orchestra. Deodhar, it would seem, was so enchanted by Ameli Todi that he included it in his phenomenal repertoire and presented it in khayal, vilambit and drut at his radio concerts.

Dinaker Rao’s comradeship with G.N.Joshi must be regarded as very significant against the background of the musical scene of that period. Joshi, as mentioned earlier, worked as music director with HMV for more than three decades. Like Dinaker Rao, he pledged himself to the task of enlisting old masters and encouraging new talent through his commercial network. It was thus natural that both the music directors came to supplement and complement the work of each other in various ways.

It is a known fact that the old maestri – vocalists and instrumentalists – were initially reluctant to perform for either HMV or AIR for reasons that ranged from superstition to remuneration. It was left to Dinaker Rao and Joshi to persuade them to become radio and disc artistes. Indeed, but for these two music directors, much of the great music of several of our all time greats would have been lost for posterity.

The audition tests held by Dinaker Rao for admitting young and up- coming artistes to AIR studios for purpose of broadcast helped Joshi to use them for commercial recording as well. Most of today’s eminent performers were thus brought into the limelight by the two stalwarts to their respective channels of operation. It is maddening to think that the last 15 years of his service with AIR must have caused Rao deep frustration and despair due to the policies introduced by the then minister, Dr. B.V. Keskar. It will be recalled that he initiated several measures that ranged from the good to the downright draconian in an attempt to reorganise the set-up. While his so-called audition policy will remain a black chapter in the history of Indian broadcasting, his scheme of appointment of producers and assistant producers over the heads of senior and capable professional executives hardly brought credit to the organisation.

The result was that Rao, whose major work till 1952, lay in the field of creative music, had now to concern himself with administrative matters which were only incidental to his responsibility in the past. To watch him preoccupied with finalising the day-to-day schedules most of the time was, for me a sad sight. It was an example of crass waste of his exceptional creative talent.

But I watched Rao do it with the kind of single-minded devotion so typical of him. It was equally typical of the man that he was none the worse for the fate that befell him. He bore it stoically. Whatever happened to hundreds of his musical compositions, I once asked him. A bland smile is what I got in reply. A similar smile greeted me when I went to Rao’s residence to congratulate him on his winning the national-level fellowship of the Sangeet Research Academy (SRA) of Kolkata. This was the only prestigious recognition that came his’ way just three years before his death.

Dinaker Rao’s involvement in matters spiritual dated back to 1936 when Zulfikar Bukhari joined AIR Bombay as its station director. It was he who introduced Rao to Master Ashraf Khan, who had made his mark as one of the most renowned actors of the Urdu and Gujarati stage and in the film world as well. He was also a leading Sufi saint, and this spiritual aspect of Ashraf Khan’s personality made a lasting impact on young, impressionable Dinaker Rao. He adored Ashraf Khan as his spiritual guru till the end.