by Rajan P. Parrikar

First published on SAWF on December 11, 2000

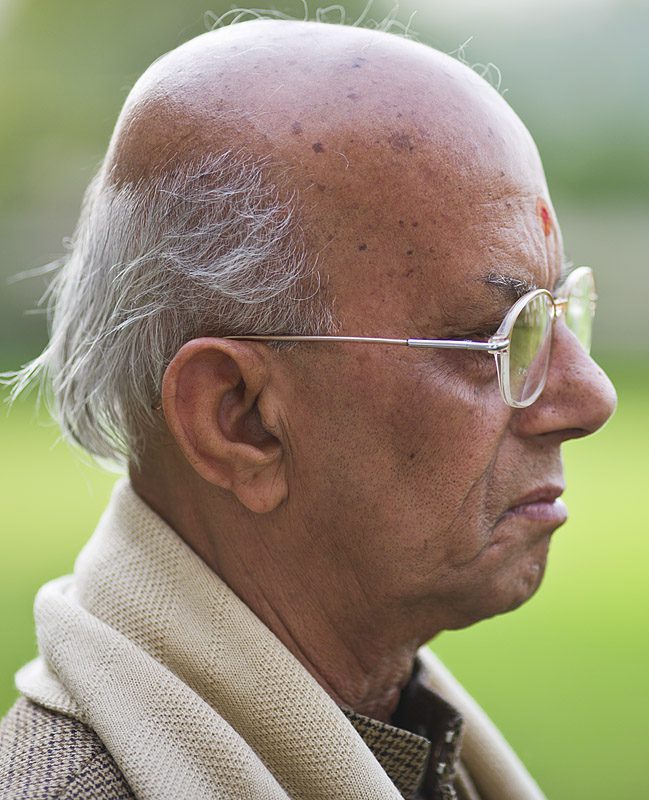

Rajan P. Parrikar (Colorado, 1991)

Namashkar.

The ragas under the “Kanada” rubric are among the most important building blocks of the Hindustani entablature. Mastery of the Kanada gestalt must form part of the mental furniture of any serious Hindustani practitioner operating in ragaspace. This melodies of Kanada Constellation are the topic of our current investigation.

Let us examine the kernel of raganga Kanada. Throughout this voyage, M denotes the shuddha madhyam. Shorn of bells and whistles, raganga Kanada may be reduced to two tonal molecules, one each in the poorvanga and uttaranga regions. They are:

(M)g (M)g M (S)R, S

and

(P)n–>P

Now, if we furnish a bridge to the above with an avarohatmak n nPMPn(M)g or a plain n P (M)g we have said essentially everything there is about the Kanada raganga. There is, however, much to be said for proper swara-uccharana something that involves kans, meend and punctuation, and without which the Kanada bhava cannot be realized.

The word “Kanada” is an apabransha (corrupt form) of “karnat.” For a historical account and occurrence of Kanada in the literature the reader is referred to Pandit Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande‘s epochal work Hindustani Sangeet Paddhati. Our focus here will be on raga structure and its praxis at the current time.

Bhatkhande enumerates 18 traditional prakars of Kanada. Of these, only about 7-8 are elemental, in the sense that they have an original, individual swaroopa. They are: Darbari, Adana, Suha, Sughrai, Nayaki, Shahana and Devsakh. The rest are composites formed by blending two ragangas or hybrids spun off by bringing together two or more ragas (eg. Basanti Kanada, Gunji Kanada). Then there are ragas realized by imprinting specialized swara clusters on the Kanada fabric (eg. Raisa Kanada, Mudriki Kanada). Another sub-group appears at first glance to fall into the hybrid class, but its members mesh so naturally with the Kanada anga that their aesthetic sensibility impels us to accord them the respect given elemental Kanadas (eg. Bageshree Kanada, Kafi Kanada and Kaushi Kanada). Incidentally, the plain ol’ Bageshree (without the explicit Kanada artifacts) was in the olden times considered a form of Kanada (vide Bhatkhande).

The casual observer of the Kanada constellation is often assailed by what appears to be a higgledy-piggledy state of affairs. A general description of the Kanada variants is a hopeless task given their wide variability. With the exception of Darbari, on which near unanimity prevails, the remainder of the Kanadas show variance in expression across regional and gharana borders. It must be emphasized, however, that there is no ambiguity apropos of the Kanada kernel itself which is at once recognizable and unambiguous. The divergence in raga-swaroopa is in the area of supporting tonal constructs.

Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang”

© Rajan P. Parrikar

Be that as it may, the tack I propose to take is the one adopted by Pandit Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang” in his classic volumes of Abhinava Geetanjali. One version is identified as canonical, the primary carrier of raga lakshanas, and deviations from that norm are suitably accomodated in discussion. My brief here is to sketch the broad strokes of the raga. For details and other minutiae the reader is referred to Ramrang’s treatise. Ramrang’s own audio illustrations will be adduced below as we run through the Kanada catalogue.

Raga Darbari Kanada

Legend credits Tansen with giving the ancient Kanada a new interpretation which we today associate with Darbari. It is a monumental raga, unmatched in Hindustani ragaspace for its gravitas, difficult in its swara-lagav, and profound for its emotional impact on the innocent and the illuminati alike.

Darbari is the premier Kanada, the flagship of the ranganga; indeed a mention of ‘Kanada’ is by default taken to mean Darbari. Occasionally it also goes by the name Shuddha Kanada.

The swara set is supplied by the Asavari that: S R g M P d n. The attack on komal gandhar is critical. Much is made of the ati-komal nature of this Darbari gandhar. However, in Hindustani music, as in most Indian music, a swara is not characterized by a single frequency point. What is of paramount important is the swara–uccharana – i.e. kans, proportion, volume, angle & direction of attack, all of which go into the making of swara. It must be underscored that the swara is not the same as ‘note.’

The komal gandhar in Darbari is ati-komal, to be sure, but the kans are far more decisive. There are two directions of approach to komal gandhar. The arohi gandhar receives a kan of rishab, the avarohi gandhar receives a kan of madhyam; in both instances the gandhar is andolita. This sui generis komal gandhar is the lifeblood of Raga Darbari Kanada. In notational form, we have:

The arohi gandhar: S R (R)g, (R)g

The avarohi gandhar: (M)g, (M)g M (S)R, S

The rishab is the vadi and an important nyasa sthana. The pancham is likewise another important location for repose. The Darbari komal dhaivat is symmetrical to gandhar in that the arohi kan is purchased from pancham, the avarohi from komal nishad. But there is an important difference – dhaivat is langhan (skipped) in avarohi prayogas whereas gandhar is indispensible:

Kesarbai Kerkar

M P (P)d, (P)d, (P)n–>P

and

S”, (n)d n–>P

Observe that dhaivat lends an austere effect in the mandra saptak; several established khayal compositions locate the sam there.

The Kanadic (P)n–>P movement is characterized first by a forceful P–kan to n and then a meend back to pancham. The aforementioned ‘bridge’ – nnPMPnMP(M)g – delivered with a forceful gamaka puts the ball back into the poorvanga court and the melodic sequence is resolved all the way back to the shadaj via (M)g M (S)R, S.

Darbari is a poorvanga-pradhana raga, where the mandra and madhya saptakas harbour most of the melodic activity. As a final remark, the tans in Darbari khayals never assume a linear profile (eg. SRgMPdn etc), but are conceived in double and triple hammered combinations (MMM PPP ddd etc) or in other vakra formulations. Forceful gamakas are liberally employed once the initial development has warmed up.

A sample chalan for Darbari is now proposed:

S, n’SRS (n’)d’, (n`)d’ n’ P`, M’ P’ (P`)d’ (P`)d`, d’ n’ R, S

S R (R)g, (R)g, M P, nP (M)g, (M)g M (S)R, S

M M P, M P (P)d (P)d, (P)n–>P, n nPMPn (M)g, (M)g M R, S

These Darbari lakshanas are frozen in this compendium by Pandit Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang”.

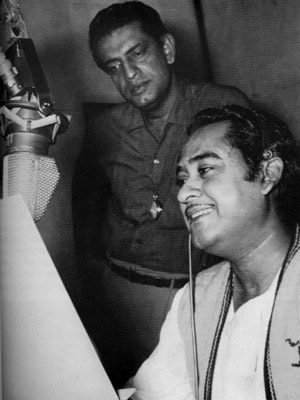

Our Darbarifest opens with a few clips drawn from the ‘light’ arena Pandit Kishore Kumar volleys a traditional cheez with preliminary alap. The composer is Bappi Lahiri, a bong of indeterminate sex.

The Kanadas have a long association with Marathi stage music and among most celebrated Darbari there is this one by Vasantrao Deshpande from the play SAUNSHAYKALLOL: mruganayana rasika mohini.

Kishore Kumar and Satyajit Ray

Mukesh‘s maiden effort was this Darbari-inspired number from PEHLI NAZAR under Anil Biswas‘ baton. The influence of Saigal on Mukesh’s gayaki is obvious: dil jalta hai to jalne do.

The next two are vintage Asha numbers: Film: LEADER, Music by Naushad: daiyya re daiyya.

Film: KAJAL, Music by Ravi: tora mana darpan.

Although Darbari is more suited to the baritone, Lata’s gestures attract our attention. From the movie MUGHAL-E-AZAM, the composer is Naushad.

Film: MERE HUZOOR, Music: Shankar-Jaikishan, Voice: Manna Dey. jhanaka jhanaka.

The classical segment begins with Jha-sahab’s superbly delivered compositions.

‘Aftab-e-Mousiqui’ Faiyyaz Khan was considered among the greatest performers of the 20th C. This 1942 mehfil recording suggests why.

Darbari is enshrined in several traditional dhrupads. The Dagars, N. Moinuddin and N. Aminuddin, reprise one such: sajana bina khelata.

Bade Ghulam Ali Khan‘s servings of Darbari were universally loved. In this unpublished 1954 Calcutta recording, he sings the traditional vilambit, bandhanwa bandho re.

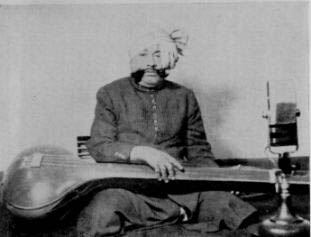

Abdul Wahid Khan

The Kirana pioneer Abdul Waheed Khan was overshadowed by his cousin Abdul Karim Khan, but had a profound influence on 20th C vilambit khayal gayaki.

Amir Khan was born to sing expansive ragas like Darbari. The just-mentioned Abdul Waheed Khan was a key influence in the formation of his musical philosophy. This has got to be among the greatest pieces of recorded music, certainly the mother of all Darbaris.

The magnificent early recordings of Nazakat and Salamat Ali have been present to my imagination for as long as I can remember. I cut my teeth on this Darbari, thanks to my father’s love of it.

Krishnarao Shankar Pandit

The Gwalior stamp from the Darbar-gayak Krishnarao Shankar Pandit: suhagana cholara.

Azmat Hussain Khan of Atrauli was Alladiya Khan’s nephew and a close relation of Agrawale Vilayat Hussain Khan. During his days in Bombay he trained a number of students including Jitendra Abhisheki. This recording is from a 1970s mehfil at the Kala Academy in Panjim, Goa.

Darbari is out and out the vocalist’s fief. To know and to feel it is to hear the great vocal masters. The feeble noises made by the current day dingdongers cut little ice. Nonetheless, two rare instrumental selections are adduced.

Ayet Ali Khan, younger brother of Allauddin Khan, and a master of the surbahar.

Abid Hussain, dhrupadiya and beena player, was a court musician at Baroda. He traced his lineage to the fabled Jaipur gharana paterfamilias “Manrang”.

From the Atrauli-Jaipur catalogue, Mallikarjun Mansur. Mansur’s voice is not a natural fit for this raga but he compensates for it with superb gamaka work.

The Darbari orgy concludes with a druta rendition by Bhimsen Joshi: jhan jhanakawa.

There is a large pool of recordings available in Darbari and the above reflects a rather personal choice.

(L-R) Azmat Hussain Khan, Alladiya Khan, Nathan Khan

Raga Adana

Although Adana is allied to Darbari it jettisons much of the latter’s ponderous baggage. There is no andolita gandhar and much of the meend work required in Darbari is eschewed. In contrast to Darbari, Adana is an uttaranga-pradhana raga, lithe and full of gusto. To conjure an image – think of that svelte leotard-wrapped babe at the aerobics class you’ve been lusting after as Adana, and your wife as Darbari.

In the arohi passages gandhar is dropped, viz., S R M P (n)d, (n)d S”. The Kanada strands are inserted via S”, (n)d n P and g M R S. In faster forays dhaivat is sometimes skipped thus leading to an avirbhava of Sarang. Indeed, some versions of Adana sideline dhaivat altogether.

The value of the Adanic nishad is of considerable interest. Many vidwans consider it to lie between the nominal komal and shuddha nishad (called chadha nishad). This is the viewpoint embraced by Jha-sahab in a brilliant demonstration of the shades of nishad. The shruti-charcha continues well past the bandish in this clip.

Adana and Darbari often commingle in ancillary genres. Shankar-Jaikishan‘s tune in BETI BETE is tilted towards Adana. Voice: Mohammad Rafi: Radhike tune bansari churayi.

Prabhakar Karekar‘s natyageeta from EKACH PYALA: zhani de kara ya.

Composer Vasant Desai‘s tune finds a happy camper in Amir Khan. From JHANAK JHANAK PAYAL BAJE .

Amir Khan

A dhrupad in Sooltala by N. Zahiruddin and N. Faiyazuddin Dagar: Shiva Shiva Shiva Shankara Adideva.

Anjanibai Lolienkar from Goa was trained by Agrawale Vilayat Hussain Khan. Another Shiva-stuti, Damaru Dama Dama baje.

Superstars in their time, the first quarter of the 20th C, the Alia-Fattu duo (Ali Baksh and Fateh Ali) from Patiala is honoured in this bandish composed by “Meherban.” It is rendered here by Fateh Ali’s grandson, the current Fateh Ali: tan-kaptan.

Bade Ghulam Ali‘s extraordinary voice takes flight in Adana. The composition is his own: jaisi kariye waisi bhariye.

A mehfil of Ghulam Hassan Shaggan.

In recent years a whole Spicmacay generation has been weaned on Mr. Jasraj‘s Mata Kalika, composed by Maharana Jayawant Singh.

This completes the Adana section. The Kanada saga continues in Part 2.