by Rajan P. Parrikar

First published on SAWF on December 2, 2002

Rajan P. Parrikar near Badami, Karnataka (2007)

Namashkar.

In this edition of Short Takes, we shine the spotlight on Raga Bageshree and its allies. Bageshree is an old and ‘big’ raga, popular with even women and children. It finds mention in the older treatises as “Vageeshwari.”

Throughout the following discussion, M = shuddha madhyam and m = teevra madhyam.

Raga Bageshree

The constituent swaras of Bageshree map to the Kafi that (Kharaharapriya melakarta in the Carnatic paddhati): S R g M P D n. Almost all versions of Bageshree can be grouped under three main jatis:

(a) Audav-Shadava: R and P are varjit in arohi, P in avarohi prayogas.

(b) Audav-Sampoorna: R and P are varjit in arohi prayogas.

(c) Sampoorna-Sampoorna: All the swaras are present, albeit in vakra prayogas.

Of these, the first – Audav-Shadava – is sufficient to define the raga-lakshanas. Most of the performed versions, however, adopt the second – Audav-Sampoorna – scheme which involves a peculiar avarohi pancham-laden tonal cluster.

Let us now examine the structure through a set of characteristic phrases.

S, n’ D’, D’ n’ S M, M g, (S)R, S

The madhyam is powerful, the melodic centre of gravity, as it were. In the avarohi mode, a modest pause on g is prescribed (it helps prevent a spillover into Kafi). Also notice the kan of S imparted to R.

S g M, M g M D, D n D, D-M, g, (S)R, S

The raganga germ is embedded in this tonal sentence. Of particular interest are the nyasa bahutva role of D and the D-M sangati.

g M D n S”

g M n D n S”

M D n S”

Each of these arohi tonal molecules is a candidate for the uttaranga launch.

S”, (n)D n D, M P D (M)g, (S)R, S

This phrase illustrates the modus operandi for insertion of pancham within a broader avarohi context. The touch of P occasions moments of delicious frisson. In some versions, P is explicity summoned in arohi prayogas such as D n D, P D n D. When the audio clips roll out there will be opportunities aplenty to sample a variety of procedures involving pancham.

S g M, M g, RgM, M g (S)R, S

Observe the vakra arohi prayoga of R. A thoughtless or cavalier approach here can lead to an inadvertant run-in with Abhogi – recall the uccharana bheda that separates Bageshree and Abhogi in this region of the poorvanga – and run afoul of the Bageshree spirit.

This completes our preamble.

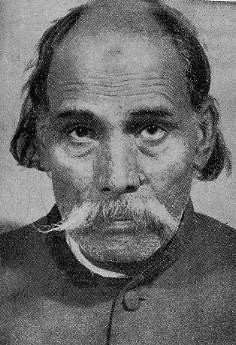

Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang”

© Rajan P. Parrikar

Pandit Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang” is on hand with his masterful précis, recorded over the California-Allahabad telephone link. He accomplishes in 4 minutes what reams of paper can’t.

A bountiful plate of samplers awaits us.

We inaugurate the proceedings with Lata‘s popular number from AZAD (1955), set to music by C. Ramchandra: Radha na bole na bole.

The great composer duo of Shankar-Jaikishan fashioned a crisp Bageshree in RANGOLI (1962), again centred on the theme of a naughty, intransigent Krishna. Nobody can match Lata in this situation: jaa’o jaa’o Nand ke lala.

Not many today appreciate the extent of sway K.L. Saigal held over the Indian musical imagination in the first half of the 20th century. Even if all Saigal-sahab did was snore, it would still have musical value. Here he wields Naushad‘s tune in SHAHJEHAN (1946): chaha barbad karegi hame.

S.N. Tripathi‘s bandish in SANGEET SAMRAT TANSEN (1962), by Pandharinath Kolhapure and Poorna Seth: madhura madhura sangeeta.

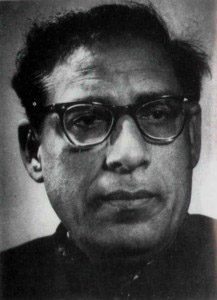

Lata Mangeshkar and Anil Biswas

Another bandish from the Bengali film KSHUDITO PASHAN (1960), composed by the au naturel, nanga, naked, sans fabrique Emperor of San Rafael, Mr. Alu (I wonder why he reminds me of a potato) and joined with the immaculate voice of Amir Khan: kaise kate rajani.

The next item features Shubha Mudgal in a dual role of composer and singer. About the verses she says: “They are from the Vaishnava temple texts that I enjoy so much, and it is what the Vaishnavas call a Malhar ka pada. I have composed other verses from the same category in Gaud Malhar, Miyan Malhar etc but I did not feel like singing this one in a Malhar and for some inexplicable reason composed it in Bageshree.”

Shubha Mudgal

(© Rajan P. Parrikar)

The terrain of Marathi natyageeta is studded with Bageshree gems. Vasantrao Deshpande hauls a couple of delectable items of which the first is from MRUCCHAKATIK: jana sare.

The much-loved dindi from SAUBHADRA (note the use of Urdu words in the mukhda): bahut din nacha bhetalo.

We now slip into our classical robes. The kernel of Bageshree runs through all these recordings. The ancillary details, in particular the treatment accorded pancham, may be of interest to the more discerning reader.

An alumnus of the Dagar school of dhrupad, Nimai Chand Boral trained under Tansen Pande (Husainuddin Dagar) and N. Moinuddin Dagar. His alap culminates in the Chautala-based prathama nada.

The composition, binati suno mori, tuned by Vishnu Digambar Paluskar is standard issue for Gwalior performers. His pupils Vinayakrao Patwardhan and Narayanrao Vyas.

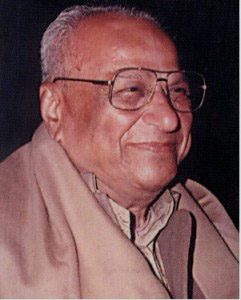

Rajab Ali Khan

The reflective temper of Amir Khan is well-matched to Bageshree’s expansive space. The rich, measured strokes of his vocal brush hold us captive to this séance. He picks up a traditional vilambit composition, bahu guna ka mana, and tops it off with a tarana.

In his day, Rajab Ali Khan (1874-1959) was known as much for his tremendous musical acumen as for his picaresque ways. A master vocalist, he was also proficient on the Rudra Veena, Sitar and Jala-Tarang. Several musicians of high standing learnt from him, among them his nephew Amanat Khan, Nivruttibuwa Sarnaik, Ganpatrao Dewaskar and others. Lata Mangeshkar, too, briefly took taleem from Rajab Ali during her stint under Aman Ali. He sings the traditional composition, kaun karata tori binati.

Amir Khan

Mushtaq Hussain Khan of Rampur-Sahaswan.

Among the most curious phenomenon in Indian music in recent times is the emergence of the “child prodigy.” There is one in every family, especially in Carnatic circles. Upon examination, however, he usually turns out to be (in Bertrand Russell‘s marvelous phrase) “more child than prodigy.” We have here a pre-pubescent Kumar Gandharva toying with the chestnut, gunda laa’o re malaniyan. This may have some curio or flutter value, but not much else.

Shaila Datar: eri piharva ghara aavo.

K.G. Ginde puts a spin on the standard Bageshree, calling it “Sampoorna Bageshree.” Here, both rishab and pancham are free-flowing. The careful listener will also sense a special sanchari or two: reeta na mori.

K.G. Ginde

A couple of instrumental selections follow.

The Chicago-based bansuri artiste Shri Lyon Leifer plays khayal in this commercial release.

K.V. Narayanaswamy sings a composition of the renowned Carnatic vocal master, M.D. Ramanathan. The raga-lakshanas come aglow in this beautiful rendition: sagara shayana vibho.

Kesarbai Kerkar felicitates Mogubai Kurdikar as

Dhondutai Kulkarni looks on

Bade Ghulam Ali Khan deals a fantabulous Bageshree in this unpublished nugget. The traditional vilambit, kaun gata bha’ili, is followed by a tarana.

The Bageshree suite concludes with a display of Atrauli-Jaipur power.

Mogubai Kurdikar‘s tarana is set to the 15-matra Sawari tala.

Kishori Amonkar matches Amir Khan swara-for-swara.

The final item is a two-part snapshot of Kesarbai Kerkar in a riveting unpublished mehfil. The presentation is not pure Bageshree for freely interspersed are tidbits of Bahar and Kafi. The second clip betrays Kesarbai’s genius, showing her for the glorious musician that she was: ruta basanta.

Raga Malgunji

Malgunji is a product of the synergy between elements of Khamaj and Bageshree. A sound understanding of such ragas is acquired only after they have done a good deal of time within the walls of your mind. They are best grasped in a two-stage process: the first round involves cultivating an intuitive feeling for their dhatu which is later reinforced by working with a representative composition. It takes experience (and, of course, a certain amount of intelligence) to sift the central features of a raga from its sidelights. Let us examine Malgunji through a set of characteristic tonal sentences.

S, D’ n’ S R G, M

This special arohi phrase represents Malgunji’s signature, a recurring theme.

S G M, G M D n D P M G M, M g R S

An otherwise Khamaj-like chalan is terminated with a Bageshree-inducing flavour. Also take measure of the powerful M.

G M D N S”, N S” n D, P D n D M G M, M g R S

Some versions sideline shuddha nishad or greatly diminish its role. As will seen shortly in Jha-sahab’s commentary, the occurrence of N is indicative of the influence of Raga Gara. Although shuddha gandhar is dominant, the Bageshree influence lurks beneath the surface: the G-M-D contour derives from Bageshree, as does the powerful madhyam.

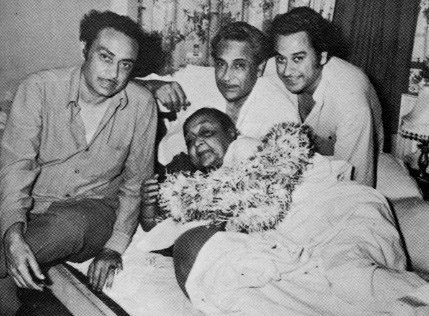

(L-R) Anoop, Ashok and Kishore Kumar with their mother

Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang” provides a synopsis.

From PICNIC (1966), Lata Mangeshkar sings to S. Mohinder‘s tune: balamva bolo na.

The uncommon splendour, purity and power of Kishore Kumar‘s voice are united in this creation of Kalyanji-Anandji for the movie SAFAR (1970). Many a college Romeo have met their waterloo mauling this song: jeevan se bhari teri ankhen.

Earlier in the 1960s, Kishore Kumar had composed and rendered this delicious number for SUHANA GEET; the movie was never released: baaje baaje baaje re kahin bansuriyan.

Malgunji is especially dear to Gwalior and is considered a specialty of that gharana. Their treatment for the most part makes do with komal nishad only; the shuddha shade, when it appears, does so in quick flourishes.

Vinayakrao Patwardhan and Narayanrao Vyas negotiate a traditional vilambit khayal, bana mein charavata gaiyya, and cap it with a tarana composed by their guru Vishnu Digambar Paluskar.

Yeshwantbuwa Joshi handles the same vilambit but in Tilwada tala.

Vishnu Digambar Paluskar

Krishnarao Shankar Pandit: aare mana samajh, and a tarana.

The final selection in Malgunji features a violin solo by Allauddin Khan. Here the two nishads (in the manner explicated earlier by Jha-sahab) are clearly observed.

Raga Rageshree

This Khamaj-that raga is constituted from the following swara set: S R G M D n. The pancham is varjya throughout, rishab is skipped (and at times, alpa) in the arohi mode. Some postulate this to be a Bageshree-anga raga by suggesting that its contours take after Bageshree with G in lieu of g. They argue that taken together with its powerful madhyam the Bageshree-anga viewpoint is tenable. We have no quarrel with that position. However, we shall record that there is also a Khamaj presence. For Rageshree’s counterpart in the Carnatic paddhati, see Natakurinji by V.N. Muthukumar and M.V. Ramana.

Typical movements in Rageshree are now suggested.

S, D’ n’ S G, G M, M G R, S

Although nominally skipped in arohi prayogas, a soupçon of R is not out of place, typically as a grace to G. To wit, S G (R)G M. Another point of note concerns the avarohi pattern leading back to S: most contemporary performances embrace the vakra G M R S cluster. The madhyam is strong, its arohi approach often mediated by a deergha G.

G M D n D, n D-G M, S” n D, M, G M (G)R S

The deergha D and the D-G coupling are points of interest. Although Khamaj tries to break through, the nyasa on the dominant M dissipates any such inchoate aspirations.

G M D n S”, D n S” G”, G” M” (G”)R”, S”

A typical uttaranga foray.

Obiter dicta:

(1) The Rageshree heard nowadays is mostly the komal nishad-only type. In practice, however, a higher shade of the nishad may accrue in arohi runs. Some musicians explicitly seek the shuddha nishad in arohi prayogas.

(2) Compare the Atrauli-Jaipur version of Khambavati with Rageshree. See In the Khamaj Orchard.

(3) A variant, Pancham Rageshree (i.e., a P-laden Rageshree), is occasionally heard in some Agra quarters.

(4) An appropriate murchhana on Rageshree can precipitate Bihag-like flavours.

Once again, Jha-sahab’s pearls of wisdom.

Lata‘s sparkler from JAAGIR (1959), a Madan Mohan composition: mane na.

Bade Ghulam Ali Khan sings for Naushad in MUGHAL-E-AZAM (1960): shubha dina aayo.

Parveen Sultana: deta badhaa’i.

Girl Power (L-R) Girija Devi, Parveen Sultana, Kishori Amonkar

Bismillah Khan adopts the older M G R S avarohi slide. Also note the unusual manner in which N is taken, for instance, at 0:15 into the clip.

The Maihar position by Bahadur Khan.

This 1935 78rpm recording of Gangubai Hangal is labeled “Khambavati.” Both nishads are pressed into service and R is also used as a kan in arohi movements (for instance ~ 0:05 during the elongation of “ho” in “hori”): Hari khelata Brija mein hori.

Agra is represented by Sharafat Hussain Khan.

Kishori Amonkar unpublished.

D.V. Paluskar

D.V. Paluskar plies a traditional Jhaptala-based composition. The deergha bahutva arohi role of G is aptly illustrated: prathama sura sadhe.

Raga Durga (Khamaj-that)

This is also known by the name “Madhuradhwani” so that it is not confused with the more familiar Durga of the Bilawal-that.

The contours of the Khamaj-that Durga assume the following form: S G M D N S” : S” n D M G S. This is not a popular raga, its base eroded by the popularity of Rageshree.

Bade Ghulam Ali Khan

Durga (Khamaj-that) is part of the Dagar family repertoire. Nimai Chand Boral‘s treatment often skips nishad altogether en route to tar shadaj but periodically figures a piquant insertion of N into the arohi flow.

Raga Rajeshwari

This is another unfamiliar audava-jati raga with the following swara set: S g M D N.

Abdul Halim Jaffer Khan on the sitar.

We close with Mohammad Hussain Sarahang of Afghanistan.

Acknowledgements

I thank Romesh Aeri, Ashok Ambardar, Sir Vish Krishnan, V.N. Muthukumar, Ajay Nerurkar and Nachiketa Sharma. Without Anita Thakur‘s commitment and enthusiasm none of this would have come to pass.