by Rajan P. Parrikar

First published on SAWF on April 1, 2002

Rajan P. Parrikar

Namashkar.

A couple of aprachalita Malhar prakars were discussed in an earlier feature, A Tale of Two Malhars. This note extends that discussion through a formal inquiry into the Malhar raganga, culminating in an exploration of its two most significant representatives: Gaud Malhar and Miyan Malhar (Note: A brief discussion on Raga Ramdasi Malhar was later added to this feature).

The Malhar group is extremely popular and its sub-melodies legion. A nimble imagination and an afternoon to spare are all it takes, it would seem, to add your personal Malhar to the catalogue.

The traditionally significant Malhars are few, and all the derivatives are essentially extensions of two central themes constituting the Malhar kernel. Earlier essays have illuminated the power of the idea of the raganga, the fundamental guiding ‘principle’ of the Hindustani melodic framework. To understand the variations, it is desirable to first internalize the tenets of the raganga.

Throughout this excursion, M = shuddha madhyam and m = teevra madhyam.

Raganga Raga Shuddha Malhar

This very old raga is the original default “Malhar” and the carrier of the principal Malhar lakshanas. However, it has become scarce in recent times with the result that “Malhar” today has come to be synonymous with the vastly popular Miyan Malhar. For a scholarly exegesis of the Malhar group, the reader is referred to the treatise Raga Malhar Darshan authored by Jha-sahab’s disciple, Dr. Geeta Banerjee. Here we shall content ourself with key points of the raga structure.

Shuddha Malhar has a pentatonic scale set – S R M P D – shared by later ragas such as Jaladhar Kedar and Durga (of Bilawal that). The chief Malhar lakshana, the quintessence of every Malhar, is:

M (M)R (M)R P

The uccharana (intonation) of rishab graced by the madhyam is crucial. The nominal M R P construct is common to other ragas (eg. Durga) but the distinction lies in the uccharana. Recall the dictum often heard in Jha-sahab’s discourses: uccharana bheda se raga bheda.

The second phrase contributed by Shuddha Malhar belongs to the uttaranga:

M P (S”)D S”, S”, D P M

Madhyam is the nyasa swara. This prayoga is heard in several Malhars, eg. Gaud Malhar.

A ponderous gait and a meend-rich contour characterize Shuddha Malhar. With its stately mien, it is ideally suited for dhrupad gayaki. A sample chalan is now written out. Later, the audio clips will bring home the nuance.

S, R M, M R (M)R P

M P (S”)D S”, S” R” S”, S”, D P M,

M (M)R (M)R P, P M, R M, M R S

Some remarks on the scale-congruent Jaladhar Kedar and Durga are in order.

Jaladhar Kedar: The primary lakshana expresses the Kedar anga, viz., S R S M, M P M, M R S. An abhas of Shuddha Malhar prevails in the uttaranga.

Durga: The key phrases are – (P)D (P)M R P and S R (S)D’ S. Both uccharana-bheda and chalan-bheda insure a melody that steers clear of Shuddha Malhar.

Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang”

(© Rajan P. Parrikar)

As always, Pandit Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang” brings to bear his knowledge, anubhava, clarity, and felicity of expression in this interview broadcast many years ago from All India Radio, Allahabad. His interlocutor is S.L. Kandara, a violin player and disciple of the sarangi maestro Ram Narayan. Jha-sahab dwells on the structure of Shuddha Malhar, spells out the highlights of the scale-congruent Jaladhar Kedar and Durga, and finally sketches a dhrupad.

A Shuddha Malhar composition of S.N. Ratanjankar rendered by his pupil K.G. Ginde reinforces its features: dhooma dhooma dhooma aaye.

To recap, the tonal molecule M (M)R (M)R P forms the soul of raganga Malhar. In recent times, the overwhelming influence of Raga Miyan Malhar has lead to the definition of a second, subsidiary Malhar lakshana involving two nishads. To wit, S, N’ n’ D’ N’, N’ S and M’ P’ n’ D’ N’ S. More on this later in the Miyan Malhar section.

Raga Gaud Malhar

Among the oldest Malhars, it predates Miyan Malhar. As the name suggests, the basic building blocks are supplied by Gaud and Shuddha Malhar. Additional material is contributed by Bilawal. Tying these diverse strands together are special sancharis. The poorvanga activity is typically initiated with clusters contributed by Gaud:

S, R G M, M G M G R G S, R G M, P M

The strong, glowing madhyam stands out. The Gaud-inspired tonal phrase paves the way for a segue into Malhar territory: S, RGM, M (M)R (M)R P

Then comes: M (M)R P, D [n] P, G P M

The n in square brackets denotes a shake on that swara (heard in the clips later).

M P (S”)D S” (from Shuddha Malhar) or P P N D N S” (from Bilawal) are the two most common modes of uttaranga launch. Also employed to good effect is a straight and quick MPDNS”. Very occasionally there’s the P D n S” in a Khamaj-like manner.

The Miyan Malhar-inspired arohi uthav – M P n D N S” – plied in Atrauli-Jaipur and some Gwalior treatments is frowned upon by the Malhar purist who considers it to be at best superfluous and at worst injurious to Gaud Malhar’s dharma. The avarohi passages reveal the influence of Bilawal – S” D n P – and Shuddha Malhar – S”, DPM.

Putting it all together, a façade of Gaud Malhar is synthesized:

– S, RGM, M (M)R (M)R P, D, [n] P

– MPDNS”R”, S”, S” D n P, D G P M

– P, P N D N S”, S” DPM, (M)R R P, G P M

– S, RGM, R G R M, G R S

The above formulation contains the essence of the raga. The nitty-gritty of the various supporting artifacts, we shall not delve into. The clips reveal them all and the discriminating reader is encouraged to bring his own measure.

Obiter dicta: A few other versions of Gaud Malhar exist. There’s one that takes in the komal gandhar only and another with both the gandhars. These are mostly favoured by the dhrupadiyas. Yet another type of Gaud Malhar adopts the posture detailed above but with an excess of Khamaj influence. And there’s the gandhar-less outlier too.

Pandit Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang” speaks on Gaud Malhar with not a word wasted in this commentary recorded over the California-Allahabad telephone line.

Gaud Malhar has found much favour with film composers. The raga was especially close to Roshan‘s heart as the next couple of clips bear out. In MALHAR (1951) he recruits Lata Mangeshkar for an exquisite rendering of the traditional bandish: garajata barasata bheejata aai’lo.

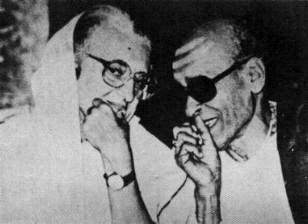

(l-r): Ali Akbar Khan, Lata Mangeshkar, Chaturlal, Ravi Shankar (note that cheeky Alu is trying to hide his beedi)

One wonders why nobody thought of systematically recording the traditional bandishes in Lata’s voice while at its peak. What a valuable document that would have made. Today, we have every Tom, Dick and Pussy (as in Ms. Pussy Galore), armed with the zeal of freshly circumcised converts, scampering to “save” and “preserve” Indian music. Indian music will survive but Indian barbers won’t as scissors give way to clippers and electronic doodads.

Chhayas of Gaud Malhar peer through now and then in this beautiful Lata number from TAJ MAHAL (1963): jurm-e-ulfat pe.

Gaud Malhar is much adored in western India (i.e. Goa and Maharasthra), the hotbed of Hindustani music and culture. I once revealed this latter fact to a gentleman who had been introduced to me as a “Bengali intellectual.” Alas, he turned out to be more Bong than intellectual. He was devastated and first turned into a pale shade of red. I thought he was going to punch me in the face (luckily, this wasn’t the “Punjabi intellectual”). Then, without warning, he went completely blue, shed a few tears and died with the words “keyhollo! keyhollo!” on his lips.

The Marathi drama SAUBHADRA is full of memorable tunes. Prabhakar Karekar, who speaks Marathi with a Konkani accent, tries his hand at this old favourite: nabha meghane akramile.

Another Goan, Ramdas Kamat, sings a marvellous composition of Jitendra Abhisheki conceived for the drama MEERA MADHURA: swapnata pahile je te.

Mehdi Hasan: phooli phool khil uthe.

For the classical banquet we have before us a spread of the fat of the land.

Jha-sahab’s guru Bholanath Bhatt came from a musical tradition that specialized in Malhars. To the repertoire handed down, Jha-sahab has added his own compelling creations. For instance, this bandish in dheema Teentala: ja re ja tu badara.

Much of the textual content of the Malhar bandishes revolves around descriptions of the rains and associated seasonal phenomena.

The Gwalior vocalists embrace this raga with relish. Malini Rajurkar‘s vilambit treatment in Tilwada adopts the old “Sadarang” composition: kahe ho hama son.

Yeshwantbuwa Joshi wields another traditional bandish, also in Tilwada, in this solid performance. Notice the very opening movement for the prayoga from komal nishad to tar saptaka rishab: piyare aa’oji.

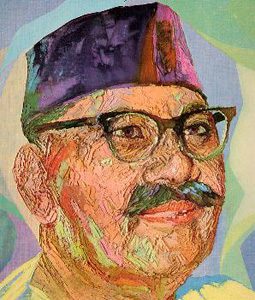

Faiyyaz Khan by Madhubhai Patel

Faiyyaz Khan flashes the Agra picture with the Sadarang bandish, kahe ho. The treatment takes a slightly different course – the n D N S tonal molecule is not employed, the tar S” is approached via M P D n S”. The lakshanas emerge beautifully, stamped with certitude and energy.

K.G. Ginde hauls in his bag of Gaud Malhars. His outline of the traditional bandish: maana na kare ri gori.

Ginde-ji’s second take is Khamaj-laced.

The final Ginde item is a komal gandhar-laden version of Gaud Malhar, through a composition of S.N. Ratanjankar: garva darun hara.

Ratanjankar has also composed in a type of Gaud Malhar that dispenses with the gandhar altogether.

Next, Salamat Ali Khan.

The Agra lass from Goa, Anjanibai Lolienkar, toys with an old bandish: balama bahar aa’ai.

Anjanibai Lolienkar

The tarana specialist of Rampur-Sahaswan, Nissar Hussain Khan.

The next selection is our Ewe-lamb, an unpublished recording of Amir Khan. The great man opens with remarks on the provenance of the bandish. The design of the mukhda is unusal with its sam placed on the rishab in a Nat-like fashion, thus creating a tirobhava and temporarily displacing Gaud Malhar. There are refreshing, magical moments to be had here.

The Atrauli-Jaipur innings opens with Kesarbai Kerkar‘s maana na kare ri. This traditional bandish was refurbished by Alladiya Khansaheb to serve as the vilambit vehicle for his vision of the raga. Kesarbai’s tans reveal extraordinary breath-control.

Kishori Amonkar breaks ranks with her gharana confrères by adopting a different composition as her mainstay: ko’u yako barajata nahin.

We return to maana na kare ri in what is indisputably the greatest performance of Gaud Malhar on record. Mallikarjun Mansur‘s tour de force is manna for the soul. This manner of singing can only come to those in whose bones the daemon of ‘madness’ has taken refuge. This cannot be the handiwork of rational beings.

Amir Khan

Raga Miyan Malhar

The prevailing lore credits Tansen with creating this raga which has come to occupy a high station in the Hindustani society. While ragangas of Malhar and Kanada support its build, raganga Malhar supplies its signature phrase: M (M)R (M)R P

The Kanada component is expressed through: n P M P (M)g (M)g M R, S

Then there’s the sui generis prayoga (mentioned earlier in the Shuddha Malhar section) with two nishads, a signpost of Miyan Malhar:

arohi prayoga: S, N’ n’ n’ D’ N’, N’ S

avarohi praoyga: M’ P’ n’ n’ D’ N’ S (or P’ n’ N’ S)

Miyan Malhar bears kinship to Raga Bahar, a member of the Kanada group. But Bahar flaunts a powerful madhyam and Miyan Malhar does not. The komal gandhar is andolita in Miyan Malhar (à la avarohatmak komal gandhar of Darbari) whereas in Bahar it is not.

The uttaranga trek assumes familiar trails: M P n D N S” or a direct M P D N S”. We now cobble up a portrait of Miyan Malhar:

– S”, N’, n’ D’ N’, N’ S

– M (M)R (M)R P, M [P] (M)g (M)g M R, S

– M P n D n D N, N S”, S” D n M P

– MPDNS”, S” R” S”, D n M P, nn P M P (M)g

– [P] (M)g (M)g M R, R S

The written word is superfluous when we have at hand the spoken word of Pandit Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang.”

A couple of film compositions of Vasant Desai flag off the audio rally. The very familiar tune from GUDDI (1971) in Vani Jairam‘s voice: bola re papihara.

Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang”

(© Rajan P. Parrikar)

Lata Mangeshkar in SAMRAT PRITHVIRAJ CHAUHAN (1959): na na na barso badal.

Lata again in a Marathi song tuned by Vasant Prabhu: jana pala bhara.

A formidable classical arsenal awaits us. We ignite the proceedings with Bhimsen Joshi‘s classic recording of that most celebrated Miyan Malhar composition credited to “Adarang”: kareema nama tero tu saheb sattara.

The selfsame bandish glistens in D.V. Paluskar‘s masterful hands. He tops it off with the druta chestnut bola re papaiyara composed by “Sadarang.”

Amir Khan‘s deeply contemplative deportment more than matches the gravitas demanded by the raga to make this an experience of the first water. The Adarang khayal is reprised, but notice the change in the placement of the sam.

We punctuate the khayal parade with a dhrupad rendering. N. Aminuddin Dagar‘s long meends draw us in.

D.V. Paluskar

An old composition in this unpublished Faiyyaz Khan segment, none the worse for its scratchy audio: bijuri chamake barase.

Among the first khayal singers in Maharashtra, Yashwant Sadashiv Pandit (popularly known as “Mirashibuwa“) was born c. 1883 and received training from Balkrishnabuwa Ichalkaranjikar. Like his gurubhai, Vishnu Digambarji, Mirashibuwa was an outstanding teacher. He also authored books on Gwalior gayaki. In this collector’s item, Mirashibuwa throws open a window to the past through which we hear echoes of the traditional Gwalior values. Notice the pace of the ‘vilambit‘ bandish.

Balkrishnabuwa Ichalkaranjikar

Bade Ghulam Ali Khan‘s gayaki is the Achilles’ spear of our age with its power to both wound and heal. This unpublished excerpt contains uncanny passages, especially the play on two nishads, and is punctuated by Ghulam Ali’s shoptalk (see Appendix at the end of this article).

The Bongs have been prattling about one Ajoy Chakraborty (allegedly listed in the Who’s Who of Tollygrunge), suggesting that he is the successor to Bade Ghulam Ali Khan. Bwahahahahahahahahahaha. What a hoot. Bongs, do you mean in terms of body weight? Please clarify. Pandit V.N. Bhatkhande has written that the Bongs know no nuthin’ about vocal music. Today, of course, this fact is known to even women and children and the qualifier “vocal” is deemed unnecessary.

Nazakat Ali Khan and Salamat Ali Khan.

The nauuuughty chick from Goa, Kishori Amonkar, in an All India Radio-Panjim recording.

Mallikarjun Mansur unpublished.

The great sitar player and teacher Mushtaq Ali Khan (1911-1989) had Barkatullah Khan for his guru.

It is always a privilege to have in our midst sarangi-nawaz Bundu Khan of Delhi.

Gangubai Hangal and daughter Krishna

A very old recording of Abdul Karim Khan toying with Adarang’s bandish.

Gangubai Hangal, sweet and young.

Jha-sahab‘s creative impulse strikes gold in this superb design: a’ayi re badariya.

It was given only to Kumar Gandharva to take bola re papaiyara to the nines. A fun ride all the way.

Kumar Gandharva

Raga Ramdasi Malhar

Ramdasi Malhar is a sankeerna raga and comes in three or more flavours. No general statement of swaroopa can be written down given the disparate strategies adopted in the various designs. The Ramdasi Malhar most often heard nowadays employs both gandhars and both nishads and the elaboration proceeds from a Miyan Malhar base. Consider the following strands in the poorvanga:

M (M)R (M)R P, P (M)g (M)g M R S

To this Miyan Malhar strip is added the following (or a variation thereof):

S R G G M, M G M, P (M)g M R S

The first half here is Gaud-like.

In the uttaranga, the Miyan Malharic M P n D N S” phrase mingles with additional special prayogas such as:

M P D N DPMGM

and

S” D n P, M P D n P

We shall now consider a set of renditions and flesh out the lakshanas germane to the specific case.

Pandit Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang” outlines his swaroopa and presents a few bandishes, including one of the G-only flavour.

K.G. Ginde presents two compositions, the first one composed by his guru S.N. Ratanjankar, the second traditional.

Amir Khan‘s is also a bi-gandhar flavour.

In the Atrauli-Jaipur design the komal gandhar dominates, the shuddha gandhar is of alpa-pramana. Consequently, the Miyan Malhar influence is strong here. Special prayogas are introduced, to wit, M P P D D n P.

Mallikarjun Mansur‘s beautiful performance in Mumbai in 1988. Notice the cameo shuddha gandhar (for instance between 0:37 and 0:38).

Mallikarjun Mansur and Indira Gandhi

The Maihar musicians play the G-only version (addressed earlier by Jha-sahab) and there prevail hints of Gaud Malhar now and then but since the shuddha gandhar takes precedence over the madhyam there is a clear demarcation. Alu whips up a spicy tikki in Ramdasi.

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to Romesh Aeri, Ashok Ambardar and Ajay Nerurkar. Sir Vish Krishnan always has much more ‘light’ material lined up than can be included. My special thanks to Chetan Vinchhi, Sanjay Havanur and V.N. Muthukumar. Anita Thakur, it does not bear repeating, is why this effort has survived and thrived.

Appendix

From B.R. Deodhar‘s Pillars of Hindustani Music:

One day [Bade Ghulam Ali] Khansaheb had a radio broadcast at 1 p.m. As I was working for the Bombay Radio Station at the time, I too had to be in attendance. After he had finished, Khansaheb said, “Wait for a while. I have sent for a taxi – we shall go together.” It was mid-july and the rain was coming down in torrents. Besides, I was hungry. But I did not have the heart to say ‘no’ to Khansaheb. The taxi came along and we got in. Water in any form made Khansaheb happy and heavy rains in particular were pure bliss for him.

Bade Ghulam Ali Khan

Some of the rain-water seeped into the taxi and began to drench us but Khansaheb seemed to be in high spirits. He said, “Come Deodharsaheb, let us go to the sea-shore; the sea would be something to be seen right now.” I protested, “For one, I am famished and besides my clothes are beginning to get wet. So let me go straight home.” However, by way of compromise I agreed to let the taxi driver take us via Marine Drive. We came to Marine Drive and Khansaheb asked the cabbie to stop his vehicle at a spot where there is a cement-concrete projection. The waves of the turbulent sea at this point were thirty to forty feet high. Khansaheb said, “Deodharsaheb, the time and this place are just right for doing riyaz. Listen.” And he began to sing. Whenever a particularly massive wave broke and water spouted up Khansaheb’s tana rose in synchronization and descended when water cascaded down. Water rose in a single massive column but split at the top and fell in broken slivers; so did Khansaheb’s tana in raga Miyan Malhar. Sometimes, if his ascending notes failed to keep pace with the surging water, he was angry with himself but tried again till it synchronized perfectly with the surging water. This went on for three quarters of an hour. I got so interested in the whole proceeding that hunger and thirst were forgotten. Finally Khansaheb’s son, who happened to be with us, said to his father, “Let us go now – it is two-thirty p.m. and we are both hungry.