by Rajan P. Parrikar

First published on SAWF on August 7, 2000

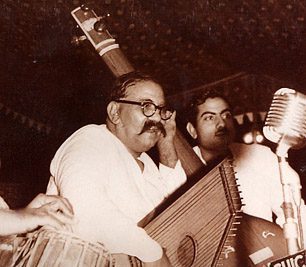

Rajan P. Parrikar and Kishore Kumar (Goa, 1986)

Namashkar.

Of all the divinities surveying India’s religious compass none is more present or more beloved to the Indian imagination than the figure of Lord Krishna. In the exalted pantheon of gods and goddesses personifying the ethos of our civilization, He is considered primus inter pares. His deeds and exploits are inscribed in our collective memory and pervasive is the influence of His ecumenical, numinous personality to those bred in the land. In this offering on the occasion of Janmasthami, we retail an episode where He plays a seminal role and wrap up the observance with musical clips – classical and ‘light’, cheek by jowl – centred on the Krishna motif.

In her book In the Dark of the Heart: Songs of Meera (HarperCollins), Shama Futehally introduces Sri Krishna:

Krishna is the eight incarnation or avatar of the god Vishnu, the preserver. He is the most intimate of gods, one who is wont to stray out of the area demarcated “worship” and steal into our everyday lives. He appears in our kitchens, our courtyards, at our washing-wells; there he is, eavesdropping upon a conversation between girlfriends; and when we are lulling a baby to sleep we might find, for one radiant moment, that we are lulling the baby Krishna. He is everywhere; he is impossible, incorrigible, unpunishable. Finally, he is love itself and the Indian soul is butter in his mischievous hands…

According to the myth proper, Krishna appeared on the earth to kill Kamsa, the wicked king of the Yadavas. He was born as the eighth child to Devaki, a sister of Kamsa. It had been prophesied to Kamsa that one of Devaki’s children would kill him, so he had the first seven babies put to death as soon as each was born. When Krishna was born, he was, with the help of divine intervention, smuggled out by his father and carried across the River Jumna to his foster parents, Nanda and Yashoda, the cowherds. It was a stormy night, and as the child was being carried across, the waters of the river rose and threatened to drown them both. The baby put out his foot and touched the flood, whereupon it receded. Krishna’s foster home was in the district of Braj, around Mathura, a region of rich pastureland still associated with the worship of Krishna.

For the first seven years of his life, he lived in the village of Gokul, then moved to Brindavan. Braj, the pastoral paradise where Krishna was brought up among cows and cowherd girls, is the eternally peaceful landscape of the heart. The figure of the baby Krishna gives to the Indian people what every baby gives to its parents at least once in their lives: an understanding that, at the very centre of life, there is joy. Stories about this enchanting child, “Nandalal” or “the Darling of Nanda”, form an entire corpus of poetry, song, dance, drama and painting throughout India.

There is no end to Krishna’s pranks and ploys to torment his adoring mother, Yashoda. In one well-known story he refuses to go to sleep until she has brought him the moon to play with. And his stealing of butter is as much a part of our lives as the exploits of our own children. With his friends in tow, Krishna goes from lane to lane, stealing butter from all the housewives of Braj, till in desperation the women take to hanging it high from the ceiling. Krishna and his friends then set about making human pyramids to reach the pots. This is a tableau which is still enacted amidst much noise and hilarity during the annual festival which celebrates Krishna’s birth…Many stories about Krishna’s childhood contain images which stretch like elastic into the order of infinity. There is, for instance, a story which tells how Yashoda looked into her son’s open mouth when he had eaten mud and saw – the universe.

When Krishna becomes a youth, he is, naturally, beauty personified. He is called by names such as Madan, the Intoxicator, or Mohan, the Charming One. In colour, he is dark as a rain-cloud, which gives him another of his many names, Shyam, or The Dark One. He wears a saffron tilak mark on his forehead, and is dressed in a yellow dhoti (cloth draped from the waist). On his head he wears a peacock plume, and a long necklace swings from his neck. His ear-rings are in the shape of crocodiles. His eyes are as beautiful as lotus petals and he holds a flute which gives him the name of Muralidhara, or Holder of the Flute. The gopis, one and all, are madly in love with him, and his unending dalliance with them gives him the title Gopinath, or Lord of the Gopis…

We inaugurate the first of the two musical segments. The birth of Sri Krishna is celebrated in this joyous composition of Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang” in Raga Nand: Nanda ghara ananda ki badha’i baje.

Jha-sahab next sings of the baby Krishna playing about the courtyard under the adoring gaze of Jashoda and the rest of the household. A delightful composition this, in Raga Kedar: painjani baje jhanana jhanana.

Among Jha-sahab’s personal favourites is his suite of magnificent compositions in Raga Tilak Kamod. For his text he chooses the prasang of that singular episode in the Mahabharata: Draupadi’s vastraharana (disrobing). The vilambit Roopak composition expresses with striking economy of verse and melody Draupadi’s predicament, and her call to the Lord, stunned that she is at the sight of her supine husbands and the other apathetic elders in the face of Duhshasana’s iniquity: mero pata rakho Murari Bheesham-Drona baithe panwara vhai.

Sri Krishna responds: begi-begi aaye Hari.

Jha-sahab’s bandish in Raga Hem Nat conjures up the image of the Lord gamboling with the gopis by the banks of the river Jamuna. Hem Nat is a hybrid formed by a judicious blend of Ragas Hem and Nat. In this composition, the lakshanas of the raga are apprehended in the opening line itself. The words are so chosen as to create a mild staccato effect to accord to Hem’s catch phrase P’ D’ P’ S (Tabla: Tulsidas Navelkar, Harmonium: Rajan P. Parrikar): rasa rachi Jamuna ke tata Hari.

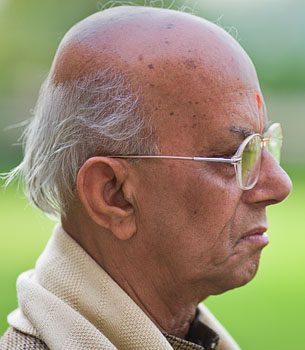

Ramashreya Jha “Ramrang”

A gently rolling Pahadi by Mohammad Rafi and Lata Mangeshkar for MISS MARY (1957), composed by Hemant Kumar: Brindavana ka Krishana-kanhaiyya.

Krishna’s rambunctious merriment is brought to life by Pandit Kishore Kumar, musician extraordinaire and founder of the now defunct Khandwa gharana. Panditji is assisted here by Lata Mangeshkar. The film is KHUDDAR and the composer is Rajesh Roshan.

Salil Chowdhary, regarded as a great Bong (a ‘great Bong’ is a Bong no longer), created this Durga-based number for JAWAHAR (1960). Lata is equal to the occasion: jagiye Gopala-lala.

The songstress of yesteryear, Juthika Roy, gives her all to Krishna. Considerable controversy prevails on just what language she is singing in. Some experts are of the opinion that it lies someplace in between Hindi and Bongspeak.

pa’on parun tore Shyam, Brija mein laut chalo, entreats Mohammad Rafi in this gem composed by Khaiyyam. With so much fervour poured into the supplication, does the Lord have the heart to refuse?

To conclude the first segment, Shankar-Jaikishan‘s classic from SEEMA (1955), based in Raga Jaijaivanti: manamohana bade jhoothe.

The Mahabharata has often been likened to a “moral minefield,” where the ‘good’ fellows don’t always play fair and the ‘bad’ fellows sometimes surpass themselves. The poet’s prism refracts before us a full panoply of emotions and desires afflicting the human soul. The exigencies of the ‘here and now’ are juxtaposed with glimpses of the transcendental. The apotheosis of Sri Krishna’s character is one of the highlights of the Great Epic. At the centre of this ‘minefield’ he stands wielding the fulcrum of Dharma. The slaying of Dronacharya, initiated by him, affords a sense of the dilemma and drama of Dharma. We relive the episode through C. Rajagopalachari‘s Mahabharata (Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan):

‘O Arjuna,’ said Krishna, ‘there is none that can defeat this Drona, fighting according to the strict rules of war. We cannot cope with him unless dharma is discarded. We have no other way open. There is but one thing that will make him desist from fighting. If he hears that Aswatthama is dead, Drona will lose all interest in life and throw down his weapons. Someone must therefore tell Drona that Aswatthama has been slain.’ Arjuna shrank in horror at the proposal as he could not bring himself to tell a lie. Those who were nearby with him also rejected the idea, for no one was minded to be a party to deceit. Yudhishthira stood for a while reflecting deeply. ‘I shall bear the burden of this sin,’ he said and resolved the deadlock!

…Bhima lifted his iron mace and brought it down on the, head of a huge elephant called Aswatthama and it fell dead. After killing the elephant Aswatthama, Bhimasena went near the division commanded by Drona and roared so that all might hear. ‘I have killed Aswatthama!’ Bhimasena who, until then, had never done or even contemplated an ignoble act, was, as he uttered these words, greatly ashamed. They knocked against his very heart – but could they be true? Drona heard these words as he was in the act of discharging a brahmastra.

‘Yudhishthira, is it true my son has been slain?’ Dronacharya asked addressing Dharmaputra. The acharya thought that Yudhishthira would not utter an untruth, even for the kingship of the three worlds. When Drona asked thus, Krishna was terribly perturbed. ‘If Yudhishthira fails us now and shrinks from uttering an untruth, we are lost. Drona’s brahmastra is of unquenchable potency and the Pandavas will be destroyed,’ he said. And Yudhishthira himself stood trembling in horror of what he was about to do, but within him also was the desire to win. ‘Let it be my sin,’ he said to himself and hardened his heart, and said aloud: ‘Yes, it is true that Aswatthama has been killed.’ But, as he was saying it, he felt again the disgrace of it and added in a low and tremulous voice, ‘Aswatthama, the elephant’ – words which were however drowned in the din and were not heard by Drona.

‘O king, thus was a great sin committed,’ said Sanjaya to the blind Dhritarashtra, while relating the events of the battle to him. When the words of untruth came out of Yudhishthira’s mouth, the wheels of his chariot, which until then always stood and moved four inches above the ground and never touched it, at once came down and touched the earth. Yudhishthira, who till then had stood apart from the world so full of untruth, suddenly became of the earth, earthy. He too desired victory and slipped into the way of untruth and so his chariot came down to the common road of mankind.

When Drona heard that his beloved son had been slain, all his attachment to life snapped, and desire vanished as if it had never been there…He threw his weapons away and sat down in yoga on the floor of his chariot and was soon in a trance. At this moment Dhrishtadyumna, with drawn sword, came and climbed in to the chariot and heedless of cries of horror and deprecation from all around he fulfilled his destiny as the slayer of Drona by sweeping off the old warrior’s head…

What are we to make of Sri Krishna’s skulduggery, his seeming incitement of the virtuous to run afoul of Dharma? Although the topic is rich, its development will not be attempted here. The following extract of Prof. R.C. Zaehner‘s commentary, taken from his concise work Hinduism (Oxford University Press), amplifies on a related theme:

The hero, Yudhishthira, the dharma-raja or, ‘King of Righteousness’, and thus the very embodiment of dharma, represents the human conscience at its best: he hungers and thirsts after righteousness, and his high sanctity is recognized by all. At the same time he has complete faith and trust in Krishna, the incarnate God; yet Krishna is always forcing him and his to do actions that are contrary not only to dharma as interpreted by the Brahmans, but also to the dharma that the King of Righteousness himself embodies and which the common conscience of the human race acknowledges to be true. For Krishna is God, the highest Brahman in personal form, and therefore beyond all the pairs of opposites, beyond good and evil. And so it is that after the most sanguinary battle in all literature in which more than a billion men have been slain in order that Yudhishthira may enter into his rightful kingdom which he was, in any case, quite content to leave in the usurper’s hands, Yudhishthira asks Krishna to instruct him in dharma, but Krishna declines to do so and delegates the task to the dying Bhishma who is the common ‘grandsire’ to the two parties to the war…

…Bhishma can tell him all there is to be known about moksha and, following a tradition that is more common in opera than in epic, he does so at enormous length though he is in his death throes, lying impaled on a bed of arrows. Krishna, however, who is a mere spectator at this scene, remains silent, though he holds the secret not only of moksha but also of the love of God for man that the liberated soul may enjoy if God so wills. Instead he imparts this saving knowledge to Yudhishthira’s younger brother, Arjuna, whom he loves as dearly as himself, before the great battle begins, and his words on this occasion form the text of Hinduism’s best-loved scripture, the Bhagavad Gita. But so little did these sublime words, which have moved the hearts of millions both inside and outside India, impress themselves on Arjuna that when the battle is over and won, he asks Krishna whether he would be good enough to repeat them since their purport has clean gone out of his head!

Why, one wonders, did the Incarnate God elect to waste his words on Arjuna rather than on Yudhishthira who was athirst to hear them? The easy answer would be that Krishna and Arjuna were linked together by eternal bonds, for they were incarnations of the eternal sages Nara and Narayana who, either together or in the person of Narayana alone, were a manifestation of the Supreme Being. This, however, obscures the real issue. Yudhishthira’s karma has not yet worked itself out: he must wait for it to ‘ripen’ and only then will he attain to moksha. To tell him the great secret prematurely would be to violate dharma itself, for the law of karma is inseparable from the eternal dharma and not even God can break it – let alone Yudhishthira who, embodiment of dharma though he is, might have been tempted to throw off the chains of karma and therefore of dharma before his time, thereby entering into the pleasure of his Lord. For the last words of Krishna to Arjuna in the Bhagavad-Gita were: ‘Give up the things of dharma, turn to me only as thy refuge. I will deliver thee from all evil. Have no care’ (BG, 18.66). To this temptation Yudhishthira might have succumbed, but his time had not yet come.

The final chapter – “Yudhisthira Returns” – in Prof. Zaehner’s book is an essay on Mahatma Gandhi where the author draws parallels and argues that Gandhi is the Yudhisthira of our time.

We initiate the second and final musical segment.

The threads are picked up by M.S. Subbalakshmi who has had an intimate association with Meera going back several decades: main Hari charanana ki dasi.

M.S. Subbulakshmi

Photo: Avinash Pasricha

Naushad‘s composition in Raga Multani is rendered by Amir Khan for SHABAB (1954). Men like Amir Khan, who could say so much in so less, don’t come by very often. We are all familiar with the term “digital compression.” To listen to this clip is to know at once what is “raga compression”: daya karo he Giridhara Gopal.

Mallikarjun Mansur takes off his Atrauli-Jaipur hat for a frolic through this traditional “Sadarang” composition in Raga Chhayanat: bansi ke bajaiyya.

Lakshmi Shankar sings a Khamaj thumri at a private chamber concert in 1995 (Tabla: Pranesh Khan, Harmonium: Rajan P. Parrikar). We pick up the proceedings in the final moments: aba na baja’o Shyam bansuriya.

A must in any Krishna catalogue is Bade Ghulam Ali Khan‘s perennial favourite, the Pahadi-based bhajan: Hari Om Tatsat.

Bade Ghulam Ali Khan

The curtain falls with a Soordas pada based in Bhairavi, delivered by the finest exponent of that raga – K.L. Saigal – in the film BHAKTA SOORDAS (1942), with music by Gyan Dutt: Madhukar Shyam hamare chor.

Acknowledgements

The author gratefully acknowledges the assistance of Sir Vish Krishnan in the above compilation. Anita Thakur of SAWF (now defunct) has been the driving force behind this entire effort.